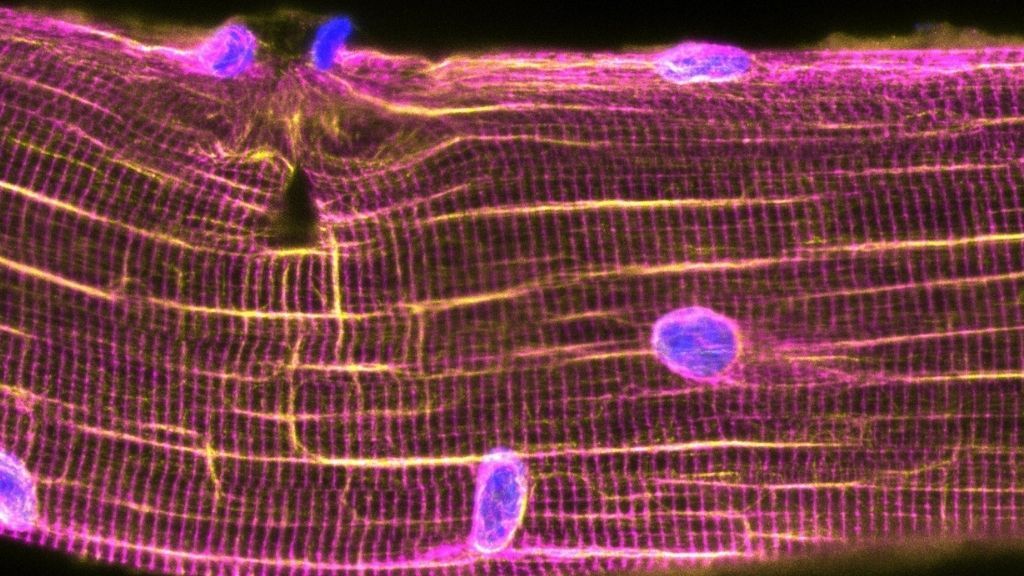

To repair a tear, the nuclei (purple) of a muscle cell move toward an injury site.

Exercising can cause muscle tears and microtears. Scientists recently discovered that the control centers of muscle cells, called nuclei, scoot towards these tiny injuries to repair them.

Researchers discovered a previously undiscovered repair mechanism after running on the treadmill. The study was published in Science on Oct. 14. These striking images clearly show that shortly after the exercise is over, the nuclei in muscle fibers begin to tear down and issue orders for new proteins to build. This will seal the wounds. This same process is likely to take place in your cells after you return from the gym.

In a commentary published in Science, Dr. Elizabeth McNally (Norwegian University Feinberg School Of Medicine) and Alexis Demonbreun (Norwegian University Feinberg Schoolof Medicine) wrote that "nuclei moved towards the injury site within five hours of injury." The repair was complete within 24 hours.

Related: Inside Life Science: Once Upon a Stem Cell

Skeletal muscles, which allow for voluntary movements such as walking, are composed of many thin tubular cells. These cells are often called "muscle fibers" because they have a thread-like appearance. According to the National Cancer Institute, a single muscle could contain hundreds of thousands to millions of muscle fibers. Each fiber also contains units of contractile machinery (known as sarcomeres), which contract and lengthen during exercise.

These sarcomeres can be overstretched by eccentric contraction. Eccentric contraction is when your muscles are forced to contract more than they contract. This type of exercise can be found in the second half of a Bicep Curl, which involves slowly lowering a dumbbell from your shoulder height to your side. Also, running downhill. According to a 2001 study published in The Journal of Physiology, sarcomeres can cause damage if they overstretch while doing eccentric exercise.

These situations are where muscle cells depend on skilled cell pit crews to fix them. Studies have shown that proteins form a "cap", which covers the injured area of the membrane. The mitochondria, the powerhouses of the cells, also help to absorb excess calcium. This is because muscle cells need to be able function properly.

The new study now suggests that muscle cells' nuclei may also rush to aid.

The researchers used adult mice to test the treadmill's tilt and collected muscle fibers after each session. They also asked 15 healthy volunteers to run on a treadmill (person-sized). Then, they biopsied muscle fibers of the vastus lateralis.

Related: Does running increase muscle mass?

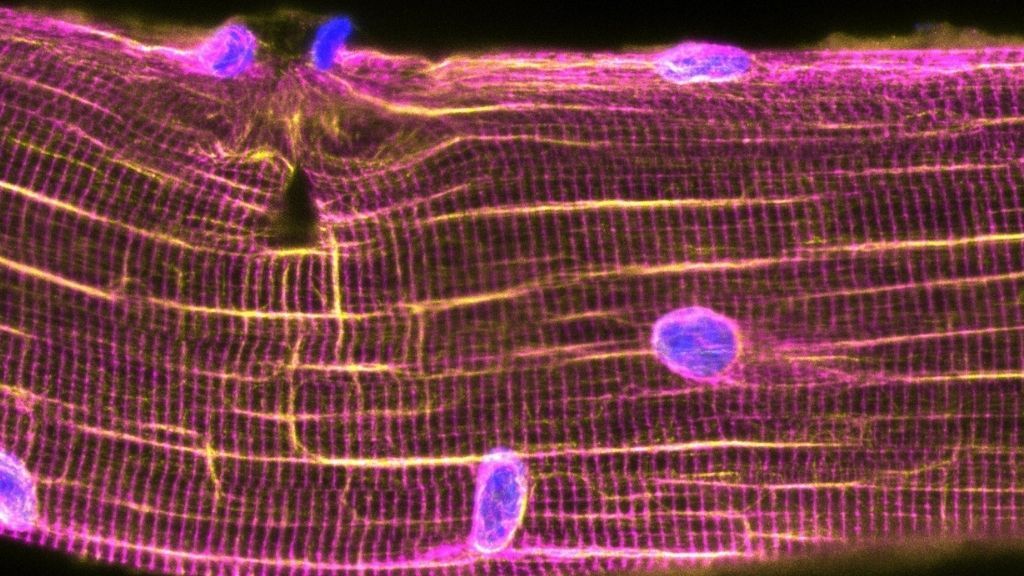

Near the injury site in a muscle fibre, nuclei are assembled. (Image credit to William Roman

Both in mouse and human muscle fibers, they found that proteins build up around tears and form "scars" within five hours of exercise. Clusters of nuclei were found in muscle fibers 24 hours after exercise. Nuclei in 5-hour samples showed a closer proximity to the tears in 24-hour samples. The team used lasers to simulate exercise-induced injury by growing mouse muscle cells in lab dishes.

The lab-grown cells quickly formed nuclei around the laser injuries in 5 hours. This created "hotspots” of protein construction near the site. The rapid explosion of mRNA molecules was triggered by the migration of nuclei. This is a type of genetic instruction manual that is built in the nucleus. Essentially, mRNA copies the blueprints encoded within DNA and then carries them into the cell where they can be used to construct new proteins. These newly created proteins help to repair and seal the damaged muscle cells.

Medical treatments that target the molecular pathways that allow nuclei to move and initiate this repair process could be developed in the future. In their commentary, McNally and Demonbreun suggested that this could speed up patients' recovery from muscular injuries.

The authors found that mice who had previously been trained on the treadmill developed less scarring on their muscles than those that hadn't. According to The New York Times, this confirms previous research that consistent training can make muscles stronger and less susceptible to tears during trained movements.

Original publication on Live Science