A lot of her friends had gotten a common prenatal test when they were pregnant with their first child.

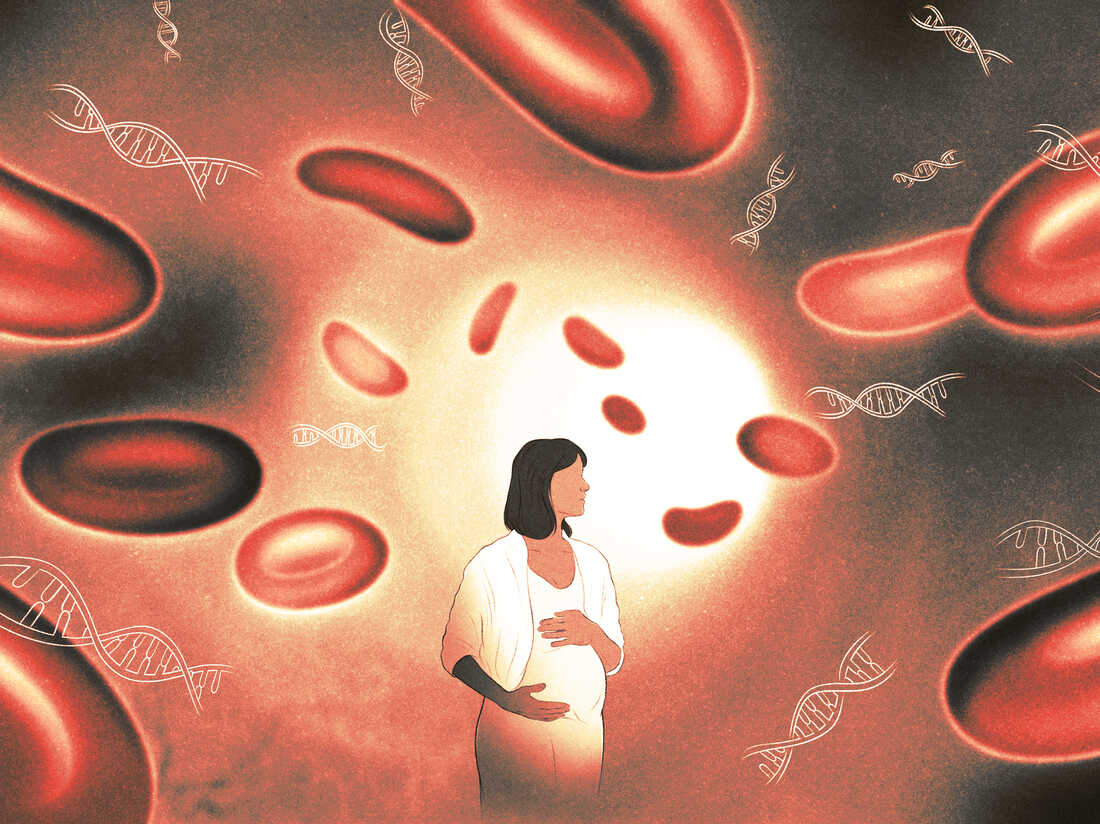

A simple blood test can be used to find out if a pregnant person is carrying a fetus. The fetus should have the same genetic make-up as the cells in the placenta that are searched for.

Over the last decade, this kind of genetic test has become the go-to method for screening pregnant women for Down syndrome, and it has reduced the number of amniocentesis procedures. Aukstikalnis was excited that the test would reveal her baby's sex, and she hoped the test would give her peace of mind.

She says that was all she was expecting. I wasn't aware that you could find out about yourself from it.

She found out more about herself. This test sent her on a medical odyssey, one that showed the promise and challenges of blood tests that can potentially zero in on cancer cells.

A pregnant woman's bloodstream contains bits of free-floating DNA associated with the fetus. Her own cells release a lot of DNA. The test results can be affected if some of the cells are cancer-causing.

Researchers have been working on a blood test that can screen for multiple cancer types at the same time. President Biden's Cancer Moonshot research initiative focuses on it.

"Imagine a simple blood test during an annual physical that could detect cancer early, when the chances of a cure are best," Biden said, adding that the National Cancer Institute is planning a large clinical trial to explore this approach.

No medical association recommends this kind of testing, and no such tests have been approved by the FDA.

There's no evidence that using certain blood tests to screen for cancer will improve people's health outcomes.

Minasian asks, "Do we really understand that in all of these different cancers at the earliest stages, they're releasing this DNA in a way that is reproducibility, that we can measure and understand that it's early or late?" We don't know a lot about this. The trials are necessary to get the information.

As pregnant people look for a test that they think will tell them something about the baby, they can be surprised by information that they didn't expect.

After she got her blood drawn and sent it off for testing, a nurse called and said there had been an error and the test hadn't produced reportable results. She had her blood drawn again.

She says it was the same type of scenario.

The patient's nurse-midwife recommended a consultation with a genetic counselor to figure out what the result was.

"I wasn't thinking about myself at all," says Aukstikalnis. I was more concerned about the baby.

The strange things in her blood sample were so rare that no one knew what was causing them. People who get test results when they're pregnant are more likely to be diagnosed with tumors.

It was hard to wrap my head around that.

Sometimes doctors look for the cancer cells' genes in the blood of patients with advanced cancer. These tests help to decide how to treat these patients.

Colin Pritchard is a professor of laboratory medicine and pathology at the University of Washington.

A blood test is a good way to detect cancer early. That is a different story.

It's harder to detect early. It is a needle-in-the-haystack problem if you want to spot the DNA released by a small number of cancer cells.

It seemed like an odd way to look for cancer. He reconsidered due to recent technological advances.

I went from being a huge skeptic to being like, 'Well, okay, this is a viable approach and this could work'

He says that they don't know who should be tested. Do you think you should be older? Is it a good idea to only be tested if you have a family history of cancer?

What kind of follow-up testing needs to be done if the screening test shows the presence of a cancer? The results of a new screening strategy that hasn't been proven cost-effective may cause insurance companies to refuse to pay for expensive tests to find cancer that isn't even present.

When Aukstikalnis and her spouse spoke with a genetic counselor, they were hit with all this uncertainty. The counselor suggested that they consider taking part in a clinical trial at the National Institute of Health, which was looking for people who had gotten ambiguous test results when looking for information about their pregnancies.

The IDENTIFY trial was designed to figure out the full range of what these results might mean so that doctors in the future would have a better idea of what to tell their patients.

Each participant in the trial would receive an all-expense-paid trip to the National Institute of Health's clinical center, the biggest research hospital in the world, for a wide array of diagnostic tests, including a full-body magnetic resonance scans, which are safe to do during pregnancy.

"It was kind of a no-brainer for me that we were going to go with the National Institute of Health and see what they could find out about it," says Aukstikalnis.

Everyone faced that choice. Amy Turriff is a genetic counselor at the National Institute of Health.

"If you have cancer, you don't feel well, you have a lump, and that's not the experience of the people being referred to us," says Turriff, "and that's just not the experience of the people being referred to us."

Some people don't participate in the study because they've been told by their doctor or cancer specialist that the test results aren't important.

The director of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development said that they faced skepticism when they started the IDENTIFY study.

"Everyone thought we were crazy in the beginning, that there's no way these healthy women are going to have cancer."

But that's not what their trial's results suggest so far, according to Bianchi, who hopes to publish interim findings from the study in a few years' time.

Over half of the people who have been Enrolled and have had the full workup have tumors. This is not a small finding. This needs to be taken seriously.

The researchers have found many different types of cancer. Lymphoma is the most common disease we have found. "We found extremely rare cancers, like 1-in-a- million type of cancers." A woman had a mass in her stomach that was the size of a fruit.

A new study out of the Netherlands followed up 48 pregnant women who had suspicious results from a cell-free DNA test. Most of the women had leukemias.

Aukstikalnis and her spouse didn't expect to hear the results of their tests until July of 2021. She didn't think the tests would show that she was sick.

At the end of the day, a team of doctors sat them down and said that she probably had cancer. The news was shocking.

It's difficult to describe the news that you've been diagnosed with cancer. She says it is an "overwhelmed" experience. At the same time, you are pregnant. There are a lot of emotions in your life. It was not easy.

She was set up with caregivers in her home state thanks to the team from the National Institute of Health.

She got a lot of help from her family and friends, as well as online support communities for pregnant women with cancer such as Hope for Two, while she was still pregnant.

Her family welcomed a baby girl in November.

She was perfectly healthy and everything went well with her delivery. I was worried about the decision to get treatment while I was pregnant because it could cause issues. It did not. She is doing great.

Unfortunately, even though Aukstikalnis had what appeared to be a clear Scan after the first line of treatment, a subsequent Scan showed that the Lymphoma had likely returned.

She underwent a stem cell transplant in the fall and was unable to see her husband or daughter for 26 days.

She's trying to take it easy now that she's with her family.

She says it's like being a newborn baby all over again. I know that we can get there, even though it will take a long time.

She hopes that her participation in the study will help other women.

She says she's grateful that she was able to get treatment at an early stage. There have been a lot of positive experiences despite the difficult situation. My focus was shifted to the things that mattered most.