There was always one thing Nathan Brosnan kept constant. His sister says that it didn't matter if he was having a mental health issue or committing crime. He was in contact with people.

The youngest of the four siblings was the one with the mental illness and addiction issues. She said he was happy and sad at the same time. He took his medication until he felt better and then stopped. He self-medicated with drugs and alcohol and became a criminal. Things would begin. He would take the medication again in jail. He was captured in that circle.

Nathan was living and working in Munruben, a locality in the city ofLogan, south of Brisbane, when he was just released from jail. He was a skilled mechanic and metal worker, and when he was well, he picked up work easily.

Nathan called his father on September 6th for a checkup. The most frequent point of contact for Nathan was his dad and his young son. Nathan hasn't called or picked up his phone in a while. He left his bank account untouched after using an ATM in the suburb of Jimboomba. Police investigations have so far failed to find him.

The disappearance of Nathan has left her and her family in a lot of pain.

She says that until you experience it, you don't understand how deep the grief is. "You're stuck." It is like moving through wet cement on a daily basis. Since he went missing, her marriage has broken down, her sister has left her job, and her parents are depressed.

The only explanation for her brother being missing is that he is dead. The family had to complete a lot of tasks, like telling Nathan's son "his dad's gone", but they can't have the rituals. She says they could have a memorial for him. We have to go through it all again if his remains are found again.

There are no answers or answers at all. Everything is open-ended and could stay that way.

Many families of the 2,500 long-term missing people in Australia are experiencing what is known as "ambiguous loss". According to forensic scientist and missing persons advocate, Associate Prof Jodie Ward, ambiguous loss is the most traumatic type of loss and the most unmanageable form of stress. That is due to the not knowing.

The Australian Federal Police launched the National DNA Program for Unidentified and missing Persons in July 2020. There were 750 sets of unidentified bones tucked away in various forensic and mortuary facilities across Australia and the program aims to connect these bones to a missing person using new forensic techniques. The program was extended this week by the Agence Franais due to the fact that testing began in December.

The goal is to end the "not knowing" for as many families as possible. We use forensic science to give as many answers as we can to the families of missing people. She says that it may not be the answer they are looking for, but it is an answer.

We’re taking a box of bones and trying to humanise them as much as possible

State and territory police have a choice. Ward and her team start looking for leads once a set arrives at the facility. The National DNA database can be used to run the results of traditional methods. New DNA techniques that have only evolved in the last 10 years are what Ward will move on to if there are no matches here.

A tool called forensic DNA phenotyping can be used to estimate a person's genetic ancestry. If a leg bone washes up on a beach and we get a DNA profile, but it doesn't match the national database, that was a dead end. I can go back to the investigator and say that it is a female missing person. She has blond hair and blue eyes.

The top stories from Guardian Australia will be delivered to your inbox every morning.

Other techniques are combined with genes. A skull can be used to create a replica face with correct eye and hair colour. A person's bones can be tested to find out where they have lived over the years. The things we eat, drink and breathe leave a mark in our bones. There are maps that show the chemical signatures plotted out across the globe.

Ward says they are taking a box of bones and trying to make them more human. If police investigations do not go well, the image and back story of this partially rebuilt person can be released in the media in the hope that someone will recognize him or her.

The program uses investigative genetic genealogy, a new field of forensic science where DNA is uploaded to public genealogy databases to try and link to a distant relative in order to catch the Golden State Killer.

There are five matches made to long-term missing persons with the five samples submitted so far. There were bones that washed up on a beach in 1977. South Australian police were able to locate a living relative of the person they believed to be the remains. Mario Della Torre went missing in 1976.

It is not possible to say how many of the 750 sets of remains they will process over the course of the program. She says that she doesn't think we could have said that a decade ago.

The Australian program needs the families of missing people to register their genes. Only 44 families have registered to date. If I don't have the right things to compare to, we won't identify every set of remains

Brosnan says that she and her family are not holding onto hope. We are still hopeful that remains will be found. We could say goodbye. It was the last goodbye.

Even if we never find out what happened to Nathan, she would be willing to give up her genetic material.

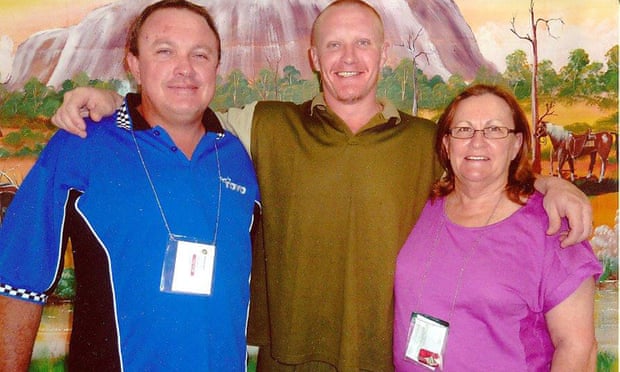

She remembers him as a good man when he wasn't fighting with the mental health and drug addiction. He was able to help. He was making people laugh. He was protective of us all.