Alida Bailleul couldn't see through the microscope. She was looking at the bones of a young hadrosaur, a duck-billed, plant-eating beast that lived 75 million years ago.

Bailleul was looking at the fossils from the Museum of the Rockies to understand how dinosaurs developed. The textbooks told her that what caught her attention should not be there. What looked to be fossilised cells were embedded in the back of the skull. There were some structures that looked like nuclei. There was a clump of chromosomes in another.

Mary Schweitzer is a professor at North Carolina State University and she was in the museum. Schweitzer did her PhD in Montana under the supervision of Jack Horner, who inspired the character Alan Grant in the movie. Schweitzer had become famous for her claim that she had found soft tissue in dinosaur fossils.

Schweitzer and Bailleul joined forces to look at the fossils further. As the world dealt with the arrival of Covid, they published a bombshell paper. The report laid out the evidence for dinosaur cells and nuclei in the hadrosaur fossils, as well as the results of chemical tests that pointed to the presence of something inside.

I don’t think we should rule out getting dinosaur DNA from dinosaur fossils - but we won’t if we don’t continue to look

Recovering biological material from dinosaur fossils is controversial. Schweitzer doesn't claim to have found dinosaur DNA, but she does say that scientists should not dismiss the possibility that it could persist in prehistoric remains.

She doesn't think it's a bad idea to get dinosaur genes from dinosaur fossils. I guarantee we won't find it if we don't keep looking.

Many of the mysteries of dinosaurs' lives could be unlocked with the help of fragments of prehistoric tissue. The prospect of having the intact genetic code from a tyrannosaur or velociraptor raises a lot of questions. Is it possible to bring back the lumbering beasts?

Rapid advances in technology have paved the way for elegant approaches to de-extinction, where a species once considered lost for good gets a second chance at life. The focus is on the creatures that humans once shared the planet with.

It is one of the most high-profile de-extinction programmes that aims to recreate the woolly mammoth and return herds of the beasts to Siberia after they have died out. The company behind the venture, Colossal, was founded by the Harvard geneticist George Church, and Ben Lamm, a techentrepreneur, who claim that thousands of woolly mammoths could help to restore the degraded habitat. The first calves could be born within six years.

It is a big challenge. Dolly the sheep was the first cloned mammal, but no living cells were found to clone well-preserved mammoths. Colossal has come up with a way to work around it. The team compared the genomes of the mammoth and elephant. The woolly mammoth had a dense coat of hair, short ears, thick layers of fat for insulation and so on.

Gene editing tools will be used to rewrite the elephant cell's genome. If the 50 or so expected edits have the desired effect, the team will insert one of the elephant cells into an Asian elephant egg. The egg should start to divide and grow into an embryo after being zapped with electricity. If the goal is to produce thousands of creatures, an artificial womb that can carry the fetus to term will be used.

One of the greatest misunderstandings about de- Extinction programmes is highlighted by Colossal. These will not be replicas of extinct animals. The woolly mammoth will be modified to survive the cold.

It depends on the reason. The animal's behavior is more important than its identity if the aim is to restore the health of the environment. If the driver is nostalgia, or an attempt to alleviate human guilt for destroying a species, de-extinction may not be much more than a scientific strategy for fooling ourselves.

The California based non-profit Revive and Restore has projects under way to help revive more than 40 species. The organisation has cloned a black-footed ferret named Elizabeth Ann, which is on course to be the first cloned mammal. The hope is that Elizabeth Ann will bring genetic diversity to the colonies of ferrets that are threatened by inbreeding.

The heath hen and passenger pigeon are two extinct bird species. The heath hen lived for decades on Martha's Vineyard, an island in Massachusetts. Scientists will be able to create a replacement bird by editing the prairie chicken's genes. The passenger pigeon project uses the band-tailed pigeon as a template for its genetics.

Ben Novak is the lead scientist at Revive and Restore and he likes to refer to rewilding as de- extinction. He says that introducing biotechnology is expanding the practice to consider species that were off the table before. The point is not to worry that animals created through de- extinction projects are not replicas of lost species. We are doing this for the sake of the environment. ecosystems don't sit around pontificating on classification schemes for the purpose of conservativism.

Humans should try to prevent extinctions. At some point in time, every species dies. Humans are driving species to the verge of extinction faster than most species can adapt. Novak says that it is a good goal to prevent all extinctions, but that the world's governments have not prioritised the preservation of the environment. He says that the majority of humans are still working against the goal. We can re-diversify the world to prevent further extinctions and prevent as many as possible right now.

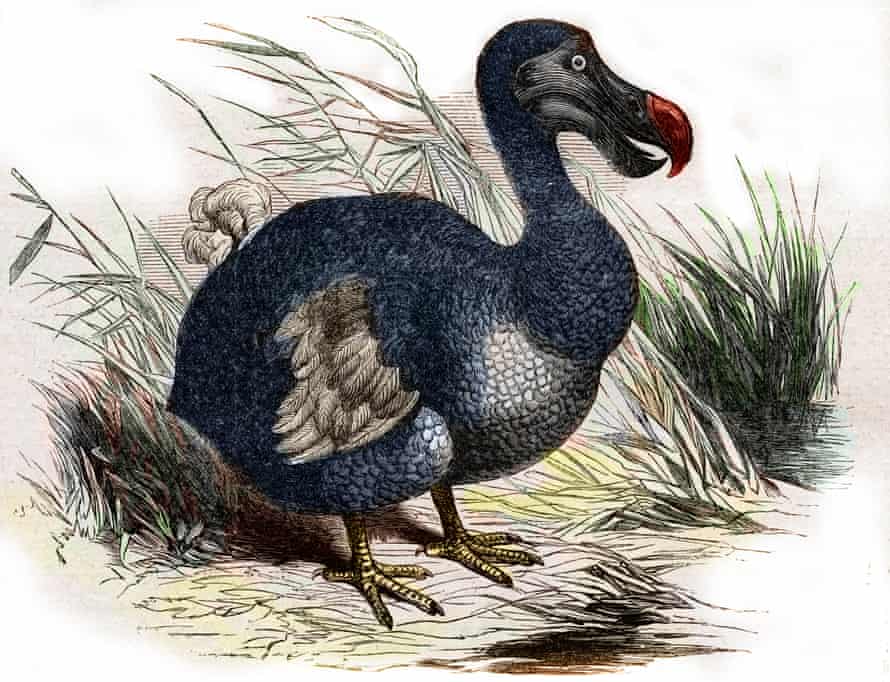

The dodo is a good place to start for de- Extinction. After humans settled on the island, the large, flightless bird died out. The dodo was also threatened by pigs, cats and monkeys that sailors brought with them.

Beth Shapiro is a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California, Santa Cruz. A dodo-like bird could be created by editing the Nicobar pigeon genome to contain dodo DNA, but only if there is a habitat for it to thrive in.

While considering what our planet will be like 50 or 100 years from now, it's important that we prioritize species and ecosystems for protection.

The rate of change in their habitats is too fast for evolution to keep up. Our new technologies can be used here. We can make more informed breeding decisions. Clones like Elizabeth Ann, the black-footed ferret, can bring back lost diversity. Our new technologies may be able to increase the rate at which species can adapt, perhaps saving some from the fate of the dodo and the mammoth.

Researchers can use living cells from the lost species and a close living relative to create a surrogate mother for the resurrected animal. These may be obstacles for dinosaurs.

Schweitzer, Bailleul and others challenged the textbook explanation of fossilisation as the replacement of tissue with rock. The fossilisation process occasionally preserves the molecule of life for tens of millions of years.

Even if soft tissue can survive in fossils, that may not be the case for dinosaur genes. Anything preserved could be very fragmented because of the breakdown of genetic material after death. The tooth of a million-year-old mammoth is the oldest of the samples that have been recovered. Scientists will be able to read the code and understand how it shaped the prehistoric creatures if older DNA is found.

Schweitzer says there are other obstacles. Researchers wouldn't have a clue how the genes were ordered on how many chromosomes if they had no idea how the genes were ordered. You have to find a living relative that can be edited to carry the dinosaur genes if you want to solve that puzzle. An ostrich might not be able to carry a T rex. Schweitzer says you go down the list. There is this and if we can solve this, then there is this. I don't believe technology will be able to overcome it.

By tinkering with bird genomes, researchers have recreated dinosaur-like teeth, tails and even hands

Life can find a way. An approach championed by Schweitzer's former supervisor is to take a living relative of the dinosaur and reprogram its genome to make birds with dinosaur-like features. Researchers have recreated dinosaur-like teeth, tails, and even hands with the help of bird genes. You end up with a dinosaur if you keep going.

Technology can't solve all of the problems. 500 or so animals might be needed for a sustainable population. Where are we going to place them? Schweitzer says that dinosaurs have a place again on this planet if modern species are wiped out. Is it fair to put one in a zoo for people to spend a lot of money to see it, but not the animal?

Schweitzer doesn't want to recreate the beasts but rather understand them better. The mysteries surrounding the dinosaurs could be revealed by the organic molecule locked up in the fossils. Is it possible that they got more nutrition from plants? How did they deal with higher carbon dioxide levels? How did they keep their large bodies?

She believes that as technology and our understanding of degradation catches up, we may get informative DNA. If we can answer the questions, that is exciting.

I don't think we'll ever see a dinosaur. I don't think it's a bad idea to bring back a dinosaur just so we can say we did it, but I don't think it's a good idea. There needs to be more reason than that.