Our brain is aware of new things around us. We are apt to over emphasize what holds our attention. When people stand out, they stay in our mind because of how much we notice their presence and how vividly we remember them.

How we think about social groups is related to our recollection of the unusual. A recent survey shows the real-life tendency to overrepresent the size of minority populations. Only 3 percent of the population of New York City are residents. 30 percent of Americans think that they live in the Big Apple, according to a nationwide survey. The survey found an overestimation of the size of minority groups. When the actual proportion is 12 percent, respondents think that 41 percent of Americans are Black.

A study published recently in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA shows that extra attention to the uncommon around us may partly explain the bad mental math that contributes to misperceptions about other groups. The authors of the study found that people exaggerate the presence of minority groups in our social environment. The effect of faulty perception on support for measures to increase diversity is something that can be mitigated by decreasing support.

According to a social psychologist who was not involved in the new study, previous research has shown that negative attitudes toward diversity and inclusion are motivated when a majority group sees a threat by overestimating minority group size. She says the findings show a cognitive response that comes before overestimation. People look at the unusual before making other judgments. Craig says that taking notice of what is uncommon to someone is a basic cognitive phenomenon in which rare things stand out.

The first author of the new study is a social psychologist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The participants underestimated the proportion of minority group members in all of the studies.

Some experiments took place at the Hebrew University, where most students speak Hebrew, a minority speak Arabic and culturally based visual signals can sometimes distinguish group members. Student participants were asked to estimate the number of Arab students on the campus. At the Hebrew University, 9.28 percent of students were Palestinian Israeli at the time of the study, but the Jewish Israeli students gave their estimate for the group as 31.56 percent, and the Palestinian Israeli students gave an estimate of 35.81 percent. The students were tested on how quickly they spotted the images of the women wearing the headscarf. They did it quickly for pictures of women wearing scarves.

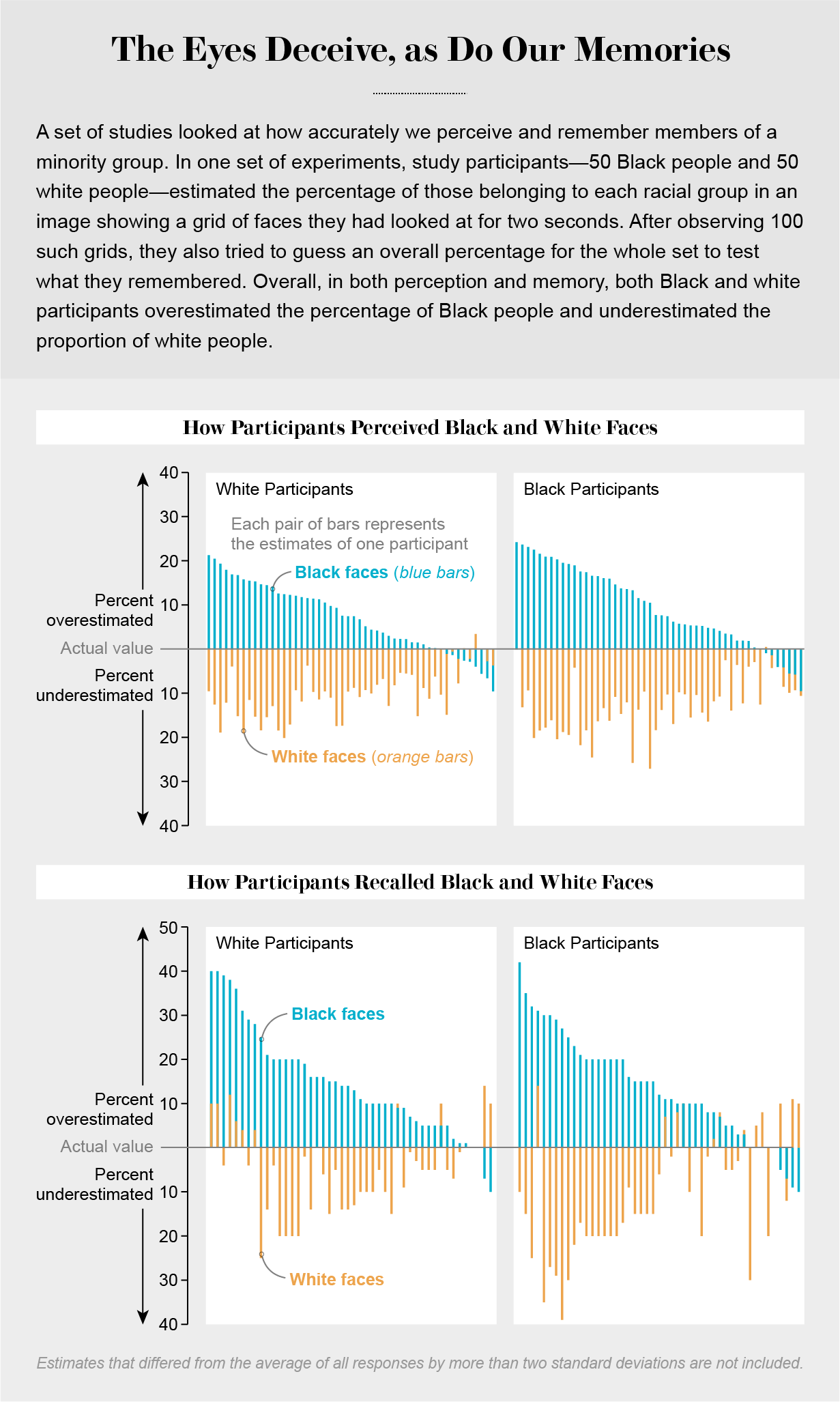

In the U.S., the researchers had participants look at a screen with a grid of 100 photographs with faces of Black people and white people in different proportions. After viewing a set of 20 grids, viewers had to estimate the percentage of black and white people present.

When 25 percent of the images were of Black people, white participants estimated the proportion of Black faces to be 43.22 percent, and Black participants put it at 43.36 percent. When 45 percent of the images were of Black faces, white participants estimated the proportion of Black people at 58.85 percent, and Black participants thought it was 56.18 percent.

In other experiments, participants were asked to estimate the proportions of Black and white faces directly after seeing each of a series of grids and to then make the same calculation after having gone through the entire set of 20 grids. They underestimated the percentage of white faces and underestimated the percentage of Black faces.

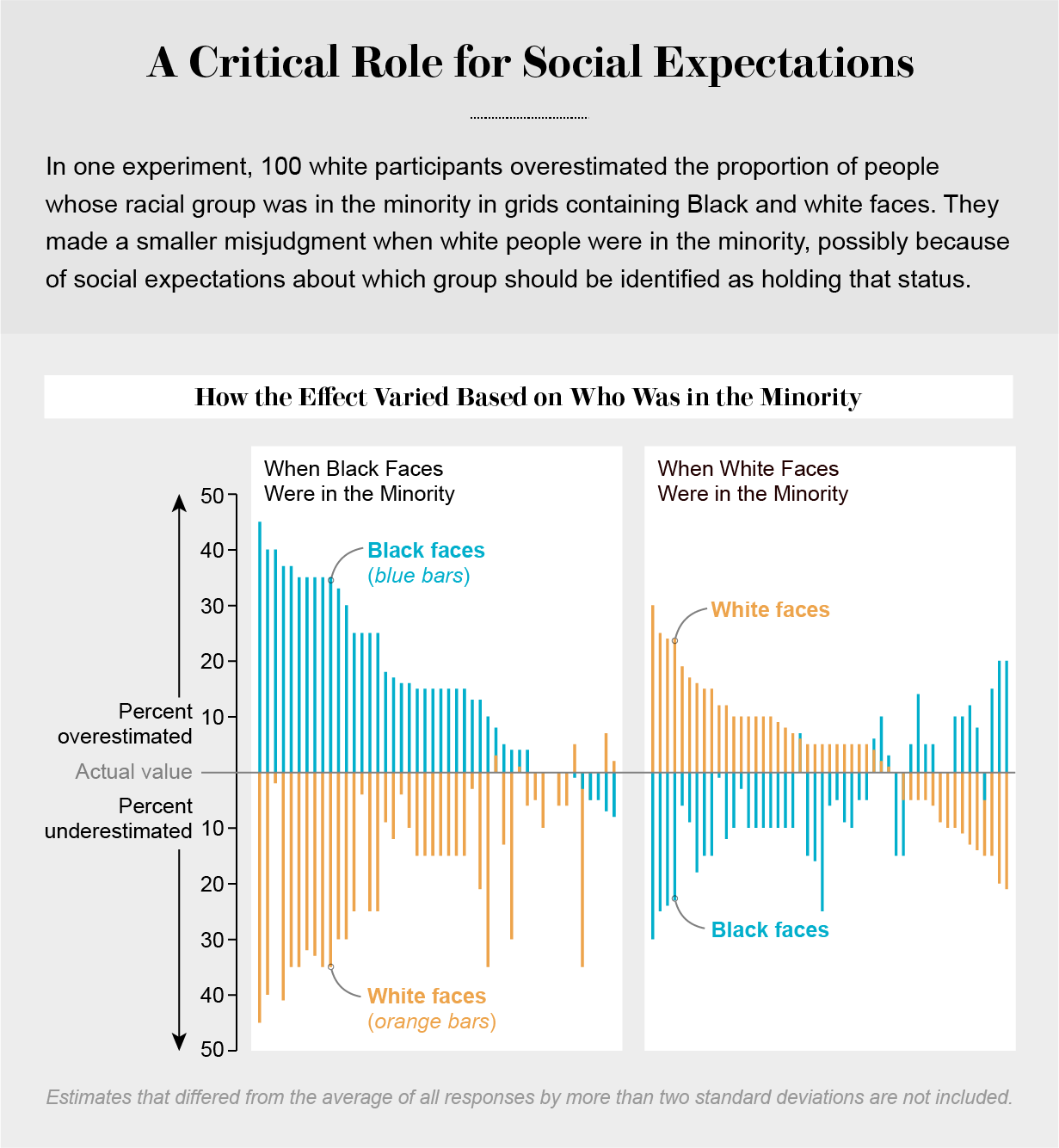

The researchers wanted to know if the expectations of which group should be in the minority would affect the outcome. They showed 100 white participants grids in which 25 percent of the faces were white, making them the minority, and another set in which 25 percent were black. The presence of faces from less common groups was judged to be higher than it really was. When Black people were in the minority, the overestimation was higher. This finding suggests that everyone has some cognitive bias that leads to overestimations of a numerical minority.

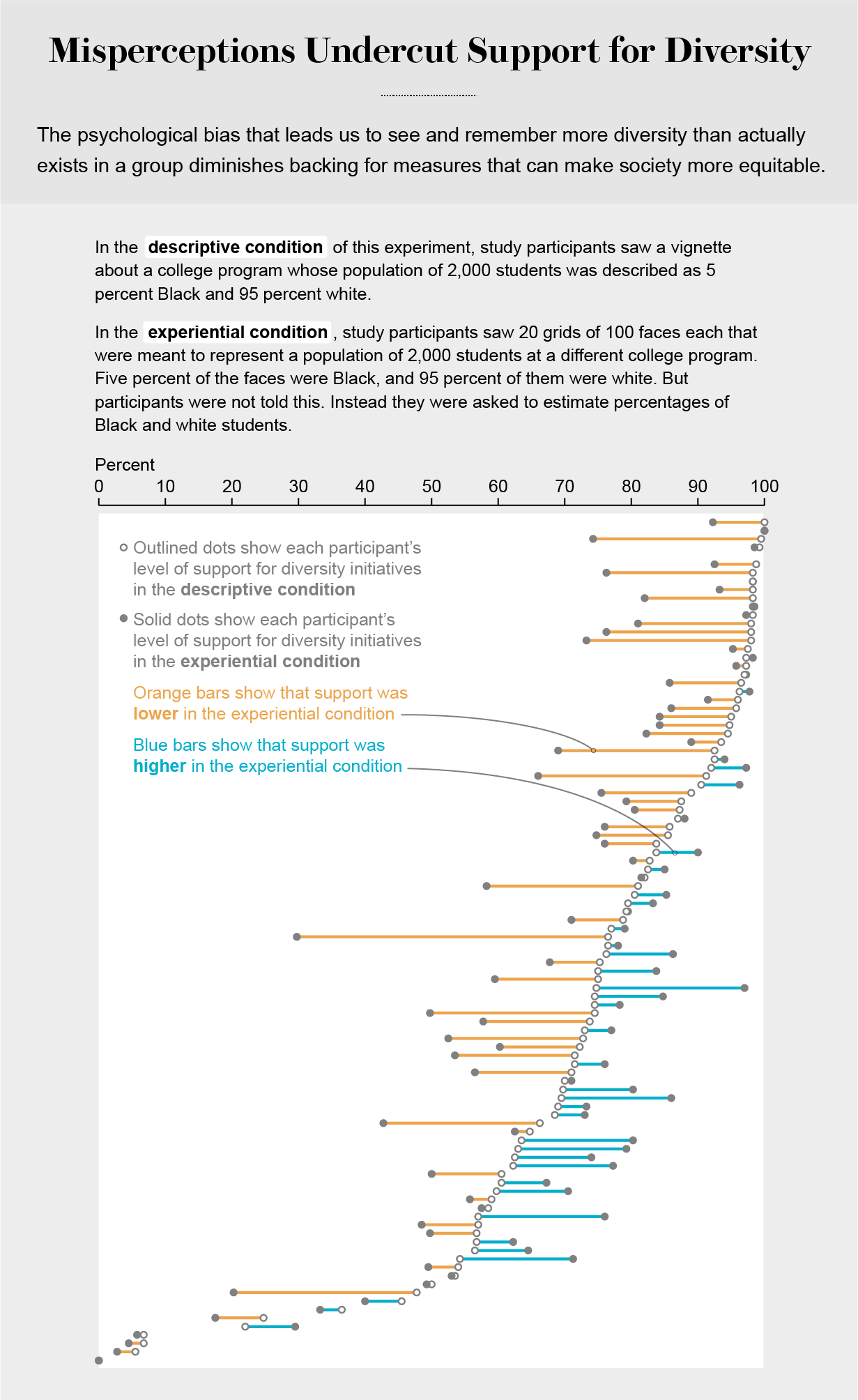

The final set of experiments looked at how psychological bias affects support for academic diversity efforts. People were shown information about college programs. Black faces made up 5 percent of the photographs viewed by participants. The group watched a video that showed that 5 percent of the students in a college program were black. After the exercises, participants were asked if more should be done to increase diversity, rating their opinion on a scale from 0 to 100.

Scientific American newsletters are free to sign up for.

Participants estimated the proportion of black faces to be 14.75 percent, not 5 percent, while simultaneously underestimating the proportion of white faces as 83.26 percent, not 95 percent. Support for a diversity-improvement program was lower in the Experiential condition with an average score of 71.07 compared with 74.5 in the descriptive condition.

The researchers found no associations between the attitudes of participants and their estimates.

The senior author of the study, a cognitive scientist at the Hebrew University, says that if people go with what their intuition tells them, it could be costly. He says that people might be less supportive of policies to enhance minority presence on a campus if they rely on impressions instead of evidence. Kardosh says that the results show that this is something we all share.

Susan Fiske, a professor of psychology and public affairs at Princeton University, was not involved in the study but edited it for PNAS. She says that the results show that the optics can be wrong, which is why this focus on awareness is so important.