James was an analyst on the east coast and went remote with the Pandemic. The company gave him a laptop and his home became his new office. He was part of a team that dealt with supply chain issues, but never had he been reprimanded for not working hard enough.

It was a shock when his team was hauled in one day late last year to an online meeting to be told there was gaps in its work: specifically periods when people, including James himself, weren't in.

No one had been watching them on the job. James became angry as he realized what had happened.

Can a company use computer monitoring tools to tell if you're productive at work? Are you about to run away from a competitor with proprietary knowledge? If you are happy?

Many companies in the US and Europe now appear to want to try, spurred on by the enormous shifts in working habits during the Pandemic, in which many office jobs moved home and seem set to either stay there or become hybrid. This is colliding with a trend among employers to quantify work in the hope of driving efficiency.

The rise of monitoring software is one of the untold stories of the Covid epidemic, says Andrew pakes, deputy general secretary of the UK labor union.

Wilneida Negr is the director of research and policy at Coworker, a US based non-profit that helps workers organize. The area of growth that went remote during the Pandemic is knowledge-centered jobs.

A survey done by Digital.com of 1,250 US employers found that 60 percent of remote employees use work monitoring software to track their web browsing and application use. Almost nine out of 10 companies terminated workers after implementing monitoring software.

The number of tools that can be used to continuously monitor employees and give feedback to managers is remarkable. Tracking technology can log keystrokes, record mouse movements, record webcams and microphones, and snap pictures without employees knowing. A growing subset uses artificial intelligence to make sense of the data being collected.

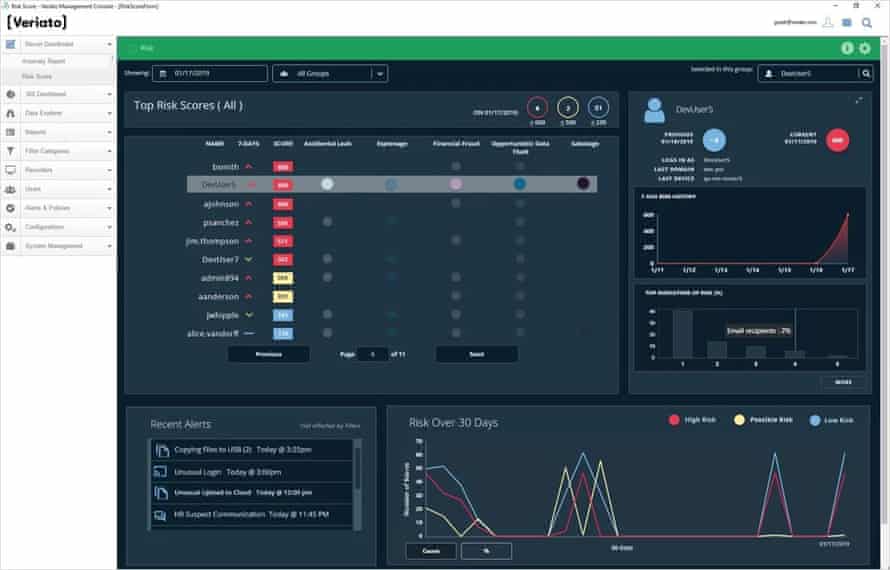

Veriato gives workers a daily risk score that indicates the likelihood they pose a security threat to their employer. They may accidentally leak something, or they may intend to steal data or intellectual property.

The score is made up of many components, but it includes what an artificial intelligence sees when it examines the text of a worker's emails and chats to purportedly determine their sentiment, or changes in it, that can point towards disgruntlement. Those people can be subject to closer examination by the company.

Elizabeth Harz, CEO, says this is about protecting consumers and investors as well as employees from making accidental mistakes.

One company making use of artificial intelligence is RemoteDesk, which has a product for remote workers who need a secure environment for dealing with credit card details or health information. It monitors workers through their webcams with real-time facial recognition and object detection technology to ensure that no one else looks at their screen and that no recording device, like a phone, comes into view. If a company prohibits a worker from drinking or eating on the job, it can cause an alert.

The description of its technology for work-from- home was a cause of concern on the micro-blogging site. Rajinish Kumar, the company's CEO, told the Guardian that the language didn't capture the company's intentions.

Tools that claim to assess a worker's productivity are poised to become the most ubiquitous. In late 2020, Microsoft launched a new product called Productivity Score which rated employee activity across its suite of apps, including how often they attended video meetings and sent emails. Microsoft apologized and reworked the product so workers couldn't be identified. Smaller companies are pushing the envelope.

Prodoscore was founded in 2016 5000 workers are being monitored by its software. Each employee gets a daily productivity score out of 100 which is sent to a team's manager and the worker, who will also see their ranking among their peers. The volume of a worker's input into the company's business applications is used to calculate the score.

Only about half of Prodoscore's customers tell their employees that they are being monitored. Sam Naficy maintains that the tool is employee friendly and gives employees a clear way of demonstrating they are actually working from home. The company argues that it doesn't come with the same gender, racial or other biases that human managers might.

Prodoscore doesn't suggest that businesses make consequential decisions for workers based on its scores. At the end of the day, it's their discretion, says Naficy. It is intended to be a complementary measurement of a worker's actual outputs, which can help businesses see how people are spending their time or rein in overworking.

Legal and tech firms are listed as customers of Naficy, but those approached by the Guardian declined to speak about what they do with the product. It is only used by a small sales division of about 20 people, according to the major US newspaper publisher. According to Prodoscore's website, a video surveillance company named DTiQ said that declining scores accurately predicted which employees would leave.

The happiness/wellbeing index will be launched by Prodoscore in an attempt to discover how workers are feeling. It would be possible for an unhappy employee to take a break.

What do workers think about being surveilled?

James and the rest of his team at the US retailer found out that the company had been monitoring their keystrokes.

When James was rebuked, he realized some of the gaps would be for employees to eat. He thought about what had happened. It wasn't what smarted that he had his keystrokes tracked. The higher-ups had failed to grasp what was going on. He spent most of his time communicating with vendors.

They looked at the individual analysts almost as if we were robots

The lack of human oversight was the reason for the discrepancy.

A lot of these technologies are largely unexplored, according to a research and policy associate at the University of California, Berkeley Labor Centre.

Productivity scores give the impression that they are objective and impartial, but are they? Many use activity as a proxy for productivity, but more emails or phone calls don't necessarily translate to being more productive or performing better. It's not clear to managers how the proprietary systems arrive at their scores.

Merve notes that systems that automatically classify a worker's time are making value judgments. She says that a worker who takes time to train or coach a college might be classified as unproductive because there is less traffic coming from their computer. Productivity scores that force workers to compete can lead to them trying to game the system rather than actually doing productive work.

Artificial intelligence models trained on previous subjects can be inaccurate and bias. There are problems with gender and racial bias documented in facial recognition technology. There are privacy issues. There could be a clue a worker is pregnant (a crib in the background), of a certain sexual orientation or living with an extended family, if a remote monitoring productInvolves aWebcam.

There is a psychological toll. Nathanael Fast is an associate professor of management at the University of Southern California who co-directs the Psychology of Technology Institute. That can cause stress and anxiety. Research on workers in the call centre industry shows a direct relationship between extensive monitoring and stress.

David Heinemeier Hansson has been campaigning against the vendors of the technology. The company he co-founded, which provides project management software for remote working, would ban vendors of the technology from integrating with it.

Hansson says that the companies tried to push back but couldn't because they couldn't be involved in supporting technology that resulted in workers. Hansson isn't naive enough to think that his stance will change things. It wouldn't be enough to quench the market if other companies followed Basecamp's lead.

Hansson and other critics argue that better laws are needed to regulate how employers can use technology and protect workers. Employers in the US are not required to specifically disclose monitoring to workers. The UK and Europe have general rights around data protection and privacy, but the system suffers from lack of enforcement.

Hansson wants managers to reflect on their desire to watch workers. Tracking may catch one goofer out of 100.

James is looking for a job that doesn't include monitoring habits.