There is no evidence that elites in England ate more meat than the rest of the country. Peasants occasionally hosted meat feasts for their rulers, according to its sister study. Major assumptions about early medieval English history have been overturned.

Picture medieval England and royal feasts with lots of meat. Historians have long assumed that free peasants were forced to hand over food to sustain their rulers throughout the year in an exploitative system known as food-rent, and that royals and nobles ate far more meat than the rest of the population.

A pair of Cambridge co-authored studies published in the journal Anglo-Saxon England present a very different picture of early medieval kingship and society.

While finishing his PhD at the University of Cambridge, bioarchaeologist Sam Leggett gave a presentation that caught the attention of historian Tom Lambert. The chemical signatures of diet preserved in the bones of 2,023 people were analyzed by Dr. Leggett at the University of Edinburgh. Evidence for social status such as grave goods, body position and grave orientation were cross-referenced. There was no correlation between social status and diet.

Many medieval texts and historical studies suggest that the Anglo-Saxon elites ate a lot of meat. They began to work together to find out what was going on.

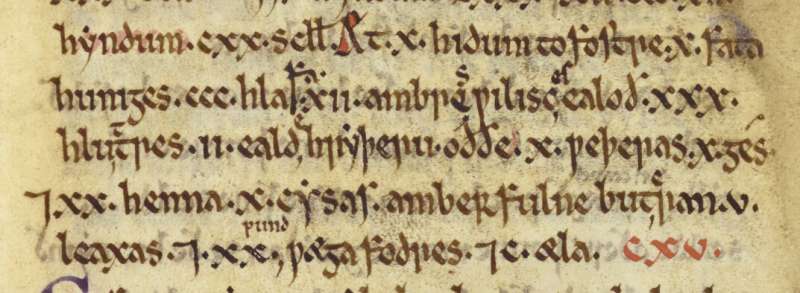

The food list was compiled during the reign of King Ine of Wessex. To estimate how much food it records and how many calories it contains. Half of the supplies came from animal protein, they estimated. The researchers used the 300 bread rolls on the list to calculate overall portions. The guest would have received 4,140 calories from 500g of meat, 500g of fish, and 500g of poultry.

A small amount of bread, a large amount of meat, a decent amount of beer, and no mention of vegetables were all found on a similar food list from southern England.

The scale and proportions of these food lists strongly suggest that they were provisions for occasional grand feasts and not general food supplies sustaining royal households on a daily basis. Historians have assumed that these were blueprints for everyday elite diet.

I have been to a lot of barbecues where friends have cooked a lot of meat. The guests are likely to have eaten the best bits and then leftovers.

I have found no evidence of people eating anything like this on a regular basis. If they were, we would be able to find signs of diseases like gout from the bones. We are not finding that.

The evidence shows that the diet in this period was very similar to that of other social groups. We should imagine a wide range of people eating bread with small amounts of meat and cheese, or eating pottages of leeks and whole grains with a little meat thrown in.

The researchers think that royals would have liked these occasional feasts because they would have eaten a cereals-based diet.

Peasants are feeding kings.

The whole oxen were roasted in huge pits at these lavish outdoor events.

Historians assume that medieval feasts were only for elites. 300 or more people must have attended if you allow for huge appetites. That means that a lot of ordinary farmers must have been there.

In Old English, feorm or food-rent is a term used to describe renders of food received from the free. It is assumed that these were the primary source of food for royal households and that the kings own lands played a minor supporting role. As kingdoms expanded, it has been assumed that food-rent was diverted by royal grants to sustain a broader elite.

The term feorm refers to a single feast, not a primitive form of tax, according to a study by Lambert. Food-rent required no personal involvement from a king or lord, and no show of respect to the peasants who were duty bound to provide it. The dynamics of communal feasts would have been very different if kings and lords attended them in person.

We are looking at kings traveling to massive barbecues hosted by free peasants, people who owned their own farms and sometimes slaves to work on them. It could be compared to a presidential campaign dinner in the US. This was a crucial form of political engagement.

Medieval studies and English political history could be affected by this rethinking. Food renders have given rise to theories about the beginnings of English kingship and land-based patronage politics.

The publication of the data from the Winchester Mortuary Chests will be eagerly anticipated by the two men who believe that the remains of Egbert, Canute and other Anglo-Saxon royals are there. The results should show us a lot about the period's most elite eating habits.

More information: SAM LEGGETT et al, Food and Power in Early Medieval England: a lack of (isotopic) enrichment, Anglo-Saxon England (2022). DOI: 10.1017/S0263675122000072Food and Power in Early Medieval England: Rethinking Feorm, Anglo-Saxon England is a book by Tom Lambert. The DOI is 10.1017

Citation: Anglo-Saxon kings were mostly veggie but peasants treated them to huge barbecues, new study argues (2022, April 21) retrieved 21 April 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2022-04-anglo-saxon-kings-veggie-peasants-huge.html This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.