It has been confirmed that the hottest rock ever discovered in Earth was really hot.

The rock, a fist-sized piece of black glass, was discovered in 2011. A new analysis of minerals from the same site shows that this heat was real.

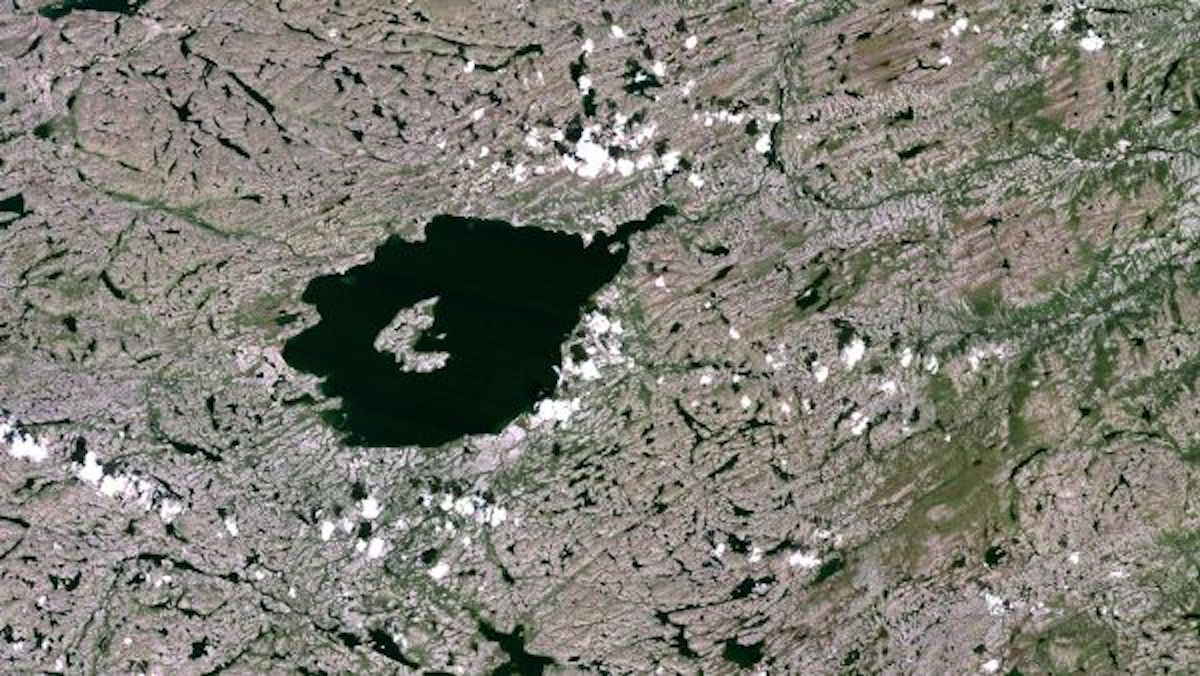

36 million years ago, the rocks melted and reformed in a meteorite impact in Labrador, Canada. A Canadian Space Agency-funded study of how to coordinate astronauts and rovers working together to explore another crater formed when Michael Zanetti picked up a glassy rock from the impact. The Mistastin crater is often used as a stand-in for such research.

The chance find was important. An analysis of the rock revealed that it contained extremely durable minerals. The structure of zircons shows how hot it was when it formed.

You must see the impact craters.

To confirm the initial findings, researchers had to date more than one zircon. In the new study, four more zircons were analyzed by the lead author and his colleagues. The samples came from different locations and gave a more complete view of how the impact heated the ground. One was from a glassy rock formed in the impact, two others from rocks that melted and resolidified, and one that held fragments of glass formed in the impact.

The results showed that the impact-glass zircons were formed in a similar fashion to the research from last year. The rock was heated to 3,043 degrees F. Tolometti said in a statement that this broad range will help researchers narrow down places to look for the most super-heated rocks in other craters.

He said that if we want to find evidence of temperatures this high, we need to look at specific regions.

The researchers found a mineral called reidite in the crater. The researchers can calculate the pressures experienced by the rocks in the impact with the presence of riddens. The impact introduced between 30 and 40 gigapascals of pressure. The weight per square inch of pressure is just one gigapascal. The pressure at the edges of the impact would have caused the rocks to melt.

The findings can be applied to other craters. The researchers hope to use the same methods to study the rocks brought back from the moon.

It can be a step forward to understand how rocks have been altered by impact cratering across the entire solar system.

The study was published in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

It was originally published on Live Science.