A unique confluence of archeology, genetics and serendipity led to a deeper understanding of how modern corn was domesticated from teosinte, a perennial grass native to Mexico and Central America.

One of the most important and successful crops on the planet is corn, according to Jonathan Lynch, a distinguished professor of plant nutrition. For decades, his research group in the College of Agricultural Sciences has been uncovering how roots play a critical role in plant development and survival.

Corn is no exception, and it turns out that early growers probably didn't know that they were selecting for root traits that supported increased development of seeds and cobs.

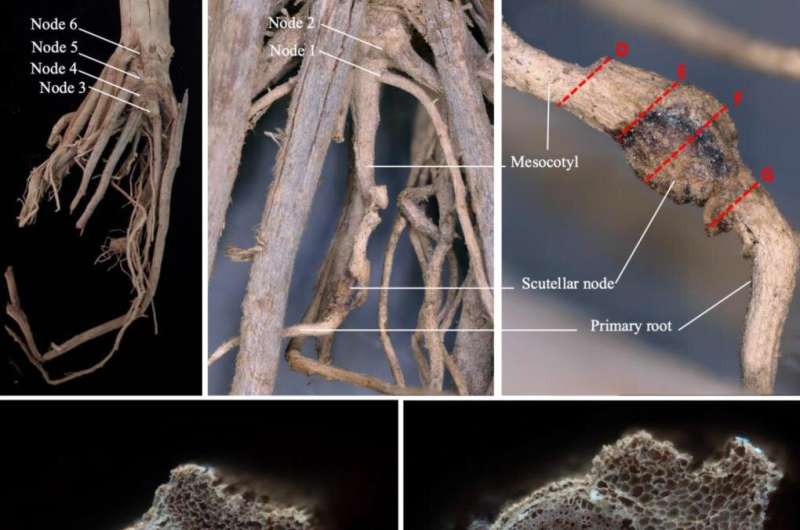

The researchers examined two ancient root stalks found in San Marcos cave at Tehuac, Mexico, and were Spearheaded by Ivan Lopez-Valdivia, initially a graduate student at LANGEBIO in Mexico and now a PhD student in Lynch's lab. They used a high-resolution phenotyping platform that combines laser optics and serial images with 3D image reconstruction and quantification to understand plants.

The technology was developed a decade ago by Lynch's research group and is now being used by a company founded by a former student. LAT was used to reconstruct the three-dimensional root structure and internal anatomy of the two ancient corn root samples, which were dated between 4,956 and 5,280 years old.

In findings published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers reported that the outer cortex cells of the roots were similar to those found in corn plants. The two corns lacked seminal roots. There are no seminal roots in teosinte.

The researchers found two genes that contribute to seminal roots in modern corn after analyzing a third specimen of the same age. The early corn specimens look like teosinte-like.

Lopez-Valdivia noted that the results show that some of the traits related to drought adaptation were not present in the earliest corn from Tehuaca.

The back story behind the research is just as interesting as the work itself. Lynch gave a presentation on his research at the National Laboratory of Genomics for Biodiversity in Irapuato, Mexico. After the presentation, he went to visit with the adviser who was Lopez-Valdivia's adviser during his pursuit of a master's degree in plant biotechnology.

Lynch hadn't even heard of the ancient maize roots that were preserved in these dry caves. That was the beginning. Ivan started this work in Mexico and finished it at Penn State as a student.

Lopez-Valdivia's thesis will focus on how evolving maize roots fit their environment through their evolution. He appreciated how his work crossed over from plant biology to simulation modeling, moving from one country to another.

The oldest remains of corn in the caves in Tehuaca, Mexico, were found by American archeologist Richard Mac Neish. In the 1960's, he found thousands of cob remains and only a dozen roots, with only one preserved scutellar node, the delicate structure from which the seminal roots develop.

The National Institute of Anthropology and History of Mexico is where the samples are being kept.

Citation: Getting to the root of corn domestication: Knowledge may help plant breeders (2022, April 19) retrieved 19 April 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2022-04-root-corn-domestication-knowledge-breeders.html This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.