The cameras aren't there yet. The fiber is already there.

There is a black box atop a utility pole on the street that used to be home to two people who won the Peace Prize: South Africa's first black president, Nelson Mandela, and the anti-apartheid activist and theologian, Desmond Tutu.

Nkosi says it always happens this way. First the fiber and then the cameras. The cameras are useless unless they can send their video feeds back to a control room where they can be monitored.

This is Vilakazi Street in the historic suburb of Soweto, a megacity that is birthing a uniquely South African model influenced by the global surveillance industry. Civil rights activists say it is already fueling a digital apartheid and unraveling people's democratic liberties.

MadelENE CRONJE is a woman.

This wouldn't have been possible five years ago. The city's infrastructure could not support sending and processing footage at the scale needed. Companies abroad began dumping the latest surveillance technologies into the country after fiber coverage expanded. The local security industry, forged under the pressures of a high-crime environment, embraced the menu of options.

The rapid creation of a centralized, coordinated, entirely privatized mass-surveillance operation has been the effect. Vumacam has over 6,600 cameras and more than 5,000 of which are in Joburg. The video footage it takes feeds into security rooms around the country, which then use all manner of artificial intelligence tools like license plate recognition to track population movement and trace individuals.

Over the years, a growing chorus of experts have argued that the impact of artificial intelligence is repeating the patterns of colonial history. In South Africa, where colonial legacies abound, the unfettered deployment of artificial intelligence is offering just one case study in how the technology is threatening to send societies back to the past.

Two streets over from Vilakazi, with its touristy polish, are still poor and surrounded by hills formed from the toxic waste of the gold mining industry.

Nkosi, a Sowetan born and bred, has spent 15 years fighting against all manner of injustices, including gender-based violence, lack of water and Sanitation, and mass surveillance that threatens civil liberties. He sounded amused as we drove by the mounds of chemicals that have polluted his community.

I'm surprised I haven't died yet.

MadelENE CRONJE is a woman.

It has been spared the cameras because it is poor. They were placed there to find paying customers. As cramped streets give way to highway and highway to affluent areas, these installations come into view: steely gray poles with thick fat discs in the middle of the road, where clusters of cameras hang like bats.

By the time we get to Rosebank, the poles are coming from concrete at a faster rate than we can count. Nkosi stops and gapes at the latest fixture, a camera that is four times the size of all the others.

That is the first time I've seen it, and it's the first time I've seen it grow. No way.

Vumacam says it doesn't use facial recognition and won't use it until the technology is regulated.

NEC XON, the South African subsidiary of the world's largest facial recognition provider, says that the cameras aren't suited for that feature.

Maybe it's coming. Maybe it isn't. That is the thing about a privatized model. It is hard to know.

MadelENE CRONJE is a woman.

Rob wants to show off the control room. The CEO of the private security company opens the door to a room with screens on the walls down the hall from the shared office space.

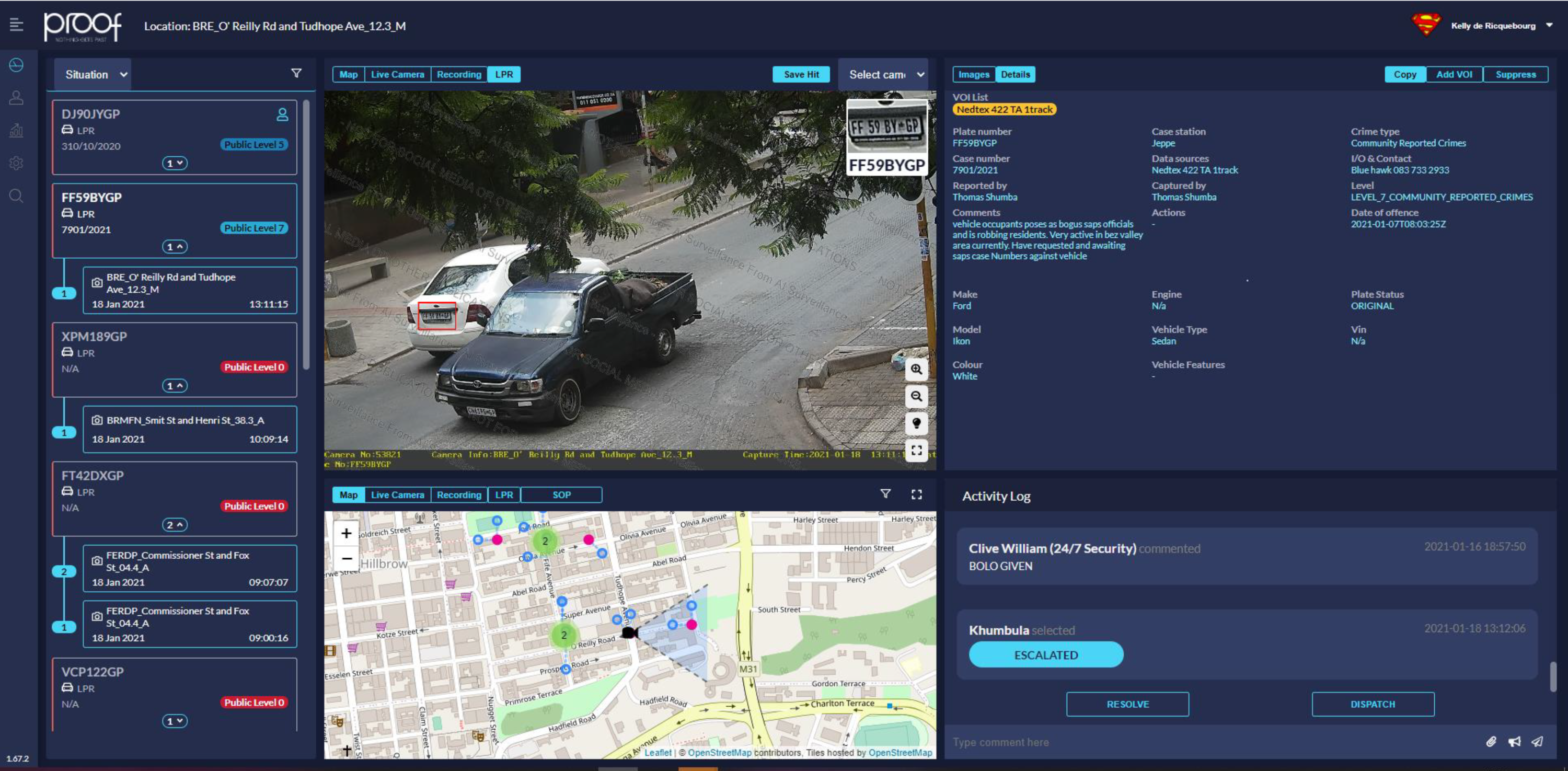

The company has been hired to watch the cameras around the city. They are mostly for show. The real action takes place on two rows of computers, where employees watch Vumacam's Proof 360 software platform.

Instead of showing dozens of video streams at the same time, Proof 360 uses artificial intelligence and other analytic tools to show the footage that triggered the security alert. License plate recognition and activity detection are included.

iSentry originally developed it for the Australian military. The software trains the cameras on 100 hours of footage so they can learn from each other. There are additional hard-coded rules for each camera. It can be programmed with barriers that people shouldn't cross and zones where cars shouldn't stop.

One by one, the alerts appear on the screen of a security worker at a monitoring station. A man has been flagged for running, a woman for standing in the hall while texting, and a woman for walking too close to a car. The operator clicks a button on all of them after reviewing them. There is a comment box and a button.

The dispatch team coordinates a response based on the alert type and the instructions of the client. Texting an on-site security guard is sometimes necessary. Sometimes it is necessary to call the police to arrest a suspected criminal.

VUMACAM.

The South African Police Service maintains a database for vehicles linked to criminal activity, so it is important that you take note of them. Don't hesitate to shoot and use high- caliber weapons. Call your security company immediately.

Vumacam uses a subscription-based model that allows entities registered with the private security industry regulator as well as the metropolitan police departments to rent access to whichever cluster of camera feeds they want. The company charged a monthly fee of about $50 per camera. It wouldn't give its latest pricing.

Private security companies such as Artificial Intelligence Surveillance are the bulk of Vumacam's subscribers, which include schools, businesses, and residential neighborhoods. After founding Vumacam, Ricky Croock stepped away to avoid conflicts with other Vumacam customers.

A Vumacam subscription has become a standard for security companies that operate in and around the more affluent suburbs and commercial areas.

Even though they don't have the same legal powers, these private security companies still dominate policing duties. South Africa has just over 1,100 police stations with just over 180,000 staff members, but there are 11,372 registered security companies and 556,540 actively employed security guards.

There is a remnant of apartheid. In the late 1970s, the National Party used police to control the unrest in opposition to the government. The opening for private players was left open by these duties taking precedence over police work.

MadelENE CRONJE is a woman.

The police force was further reduced as a condition of post-apartheid reform. The country's staggering rates of crime made the private security industry grow. In the last fiscal year, South Africa had more homicides than the US.

The police and communities were encouraged to work with private agencies. The evolution of the private security sector has been a result. There are paramilitary units everywhere, with uniformed men in tactical vehicles toting big guns. They are more common than the police. They serve paying clients, not the public interest.

The government failed to meet the demands of private citizens and businesses, just as it failed to provide boots on the ground. According to city officials, the first cameras were installed in 2009. The city has been plagued by media reports of malfunctioning cameras. The 25 that were installed on Vilakazi Street are gone.

To support MIT Technology Review's journalism, please consider becoming a subscriber.

The CEO of Vumacam, Croock, is a product of the security industry in South Africa, having previously operated a private patrol and monitoring service in the more affluent suburbs. With the introduction of fiber internet, he was able to add internet-connected cameras and artificial intelligence to his security company's offerings.

Hikvision, a Chinese company, and Vumacam, a Swedish company, collaborated to provide the hardware while iSentry and Milestone provided the software. From there, it collaborated with private agencies patrolling wealthier residential areas and erected poles with high-definition cameras where they wanted to put them.

Vumacam promised regular maintenance, high uptime, and storage of the footage for up to 30 days, during which officers and legal representatives could request a more permanent copy for use in crime investigations. 50 security companies were subscribed to its service. Vumacam wouldn't say how many customers it has.

MadelENE CRONJE is a woman.

Adoption has been sought in malls, office buildings, and even people's homes. It doesn't have its own cameras in these spaces, but customers can connect their existing feeds to Proof to monitor public and private spaces.

Vumacam is pushing a new level of coordination to fight criminal activity after achieving market penetration. It claims to have a way to track criminals from the moment they commit a crime to when they try to escape.

The platform allows users to add vehicles that have been reported stolen or suspected of being used to commit a crime to their own private database or a shared database that allows all users to work together to track cars.

Vumacam claims that this approach is quicker than waiting for a police investigation. Users don't need to file a crime report and get a case number from the police before adding a plate number. It won't take me long to get a case number. It takes me up to 48 hours.

If a license plate in the shared database doesn't have a case number after 48 hours, it's deleted. There is no transparency or mechanism for public accountability about how thoroughly this cleaning is done, nor is the same process applied to plates stored in each user's private database, meaning any plate number could be added without any vetting. Cars could be monitored and pulled over for a variety of reasons.

During joint operations between the police and security companies, apprehensions can be carried out. Private security companies are sometimes asked by the police to use VumaCAM's network to avoid the bureaucracy of their own system.

During the first seven months after its cameras were installed, Vumacam says it aided in the apprehension of 97 vehicles and the arrest of 85 individuals. Pearman says it was not aware of whether the arrests led to convictions.

There is a person named Karen Hao.

When two cars show up in different locations with the same plate numbers, a system to detect license plate cloning is built by Vumacam. Third-party developers can add their own applications to the platform and distribute them to its users.

It is extending its physical infrastructure to the rest of the country. Croock says that the company will switch to a new model later this year, where customers will pay a flat fee to get access to the full network of cameras. Agencies will still be able to view the alerts in their jurisdiction, but they will also be able to view any feed in the country.

Vumacam will be able to place poles and cameras regardless of whether there are paying customers nearby.

We need to make sure that we get the coverage we need so that the vehicles can't hide from the system.

The crime is true. On the day we walked around Rosebank with Nkosi, two people called out warnings to each other. They will take it, and you will cry too much, said the other.

Both Nkosi and the South Africa based reporter had their phones stolen just days before our meeting. In the last three months of the year, 165,000 violent crimes were reported to police nationwide.

Roseveare, who oversaw the company's initial installations, says that Craighall Park and Craighall, two suburbs that share a residents association, were eager to be early adopters. He admits that it would be difficult to prove that they deterred crime.

There are now 159 cameras in both communities, including 70 with license plate recognition, at all the exit and entry points.

Why the crime exists in the first place is absent from the conversation. Industrial societies have shown that inequality drives crime. South Africa is the most equal country in the world, but the gap is deeply racialized. Half of the country lived in poverty in 2015, and most of them were black.

predominantly white people who have the means to pay for surveilled, and predominantly black people who end up without a say about being surveilled.

Artificial intelligence tools like facial recognition and anomaly detection don't always work, and the consequences aren't evenly distributed. Black people are more at risk of having facial recognition software make a false identification when footage is recorded outdoors.

In many ways, the cameras have re-created the digital equivalent of passbooks, or internal passports, an apartheid-era system that the government used to limit Black people's physical movements in white enclaves. White people were not required to hold the passbooks. Pearman says the claims are meant to create fear and not hope where technology is successful in fighting crime.

The privatization of public safety has made it difficult to discuss how the same money could be spent to alleviate the poverty that fuels crime. Companies see a chance to make money.

Nkosi says that they are essentially monetizing public spaces and public life.

Pearman says that the technology is for the purpose of preventing crime.

MadelENE CRONJE is a woman.

During the Pandemic, crime decreased, but it has once again exploded. Many companies that we interviewed argued that more investment in surveillance technologies was justified.

NEC XON's business lead for surveillance says that there has been a huge effect on criminal activities because of the proper installation and use of surveillance technologies.

Security firms are trying to improve their facial recognition capabilities. The technology relies on a database of wanted individuals to compare faces. One security provider is working with NEC XON to implement a system that uses mugshots of suspects wanted for a wide range of crimes. Both companies want to share the system with the rest of the security industry.

There have been cases in which facial recognition has been used on people with no criminal record. In 2016 when black students protested against high tuition fees, NEC XON collected faces from photos and videos that were circulating on social media and compared them to university databases of student ID photos. The aim was not to stop the protesters, but to determine if they were students and prevent damage to the university property, which is estimated to have totaled 586 million rand.

Students said they felt criminalized when protests erupted again five years later. Ntyatyambo Volsaka, a 19-year-old law student and activist, says that police arrived with riot gear, tear gas, and rubber bullets.

He says that they are trying to make sure that everyone is getting an education, but the police treat them like animals.

The same companies are building systems around the world. South Africa is a place to perfect their technologies. Kyle Dicks, a sales engineer for Axis Communications, says that South Africa is a good place to test artificial intelligence.

Vumacam's camera network has met little resistance since it was launched.

The JRA, a body tasked with ensuring that anyone who erects structures on municipal walkways doesn't hold up traffic or cut into power cables or water mains, was an unlikely champion of privacy rights. The company needed JRA approval since their cameras are mounted on special poles.

The JRA refused to grant Vumacam further permission because the company would use the cameras to spy on the public. The agency said it wouldn't start until the city released a framework to regulate the cameras. Vumacam took the agency to court.

There is surveillance.

The JRA lost the case, but not the privacy debate. The judge ruled that the JRA's job was to protect the integrity of road infrastructure. The court refrained from issuing judgement on the alleged privacy violation.

There have been no further litigation from civil society organizations since then. People are worried about where their next job is going to come from, where their food is going to come from, and the political instability in the country, according to Nkosi. We haven't educated our public enough about the dangers of surveillance and what it means in a democratic society.

The questions raised by the lawsuit have grown more urgent. The global surveillance industry has always been open to new ideas. Os Keyes, a PhD candidate at the University of Washington, says that the US government is the most important institution in shaping their direction through their standards and vendor rankings.

Many of the technologies being used in South Africa have developed with the US market in mind. Technology and ideology are beginning to flow back in that direction.

The company wants to find clients in the US that will feed their footage to its control room and monitoring staff in South Africa. The cheaper local wages will give the company a competitive edge, as will its experience handling security in the South African market.

Vumacam's model has begun to be adapted to other markets. It moved into Nigeria, where it is placing cameras on existing infrastructure rather than building its own poles. Croock says that it could focus on selling its platform in other places that have existing camera networks.

There are signs that the rest of the industry is moving towards a platform-based approach. Anyone can build facial and license plate recognition applications for its software with the help of Milestone, the video management tool that Proof is built on. The US and South Africa have offices for Axis Communications, which recently launched its own platform.

NEC, the parent company of NEC XON, plans to launch a new product called NEC Nexus that will allow government agencies to combine their watchlists in a way that is similar to the centralization of license plate databases. There are no current plans for the implementation of Nexus in South Africa, although it will be rolled out globally, as it is currently being trialed in the UK, where NEC has the largest pilot of live facial recognition.

MadelENE CRONJE is a woman.

Nkosi is worried about what could happen next. The Black Lives Matter movement in the US and the Uyghur minority in China were targets of mass surveillance by governments around the world after they embraced these advances under the pretense of public safety.

The state has no capacity to run such a large network of cameras, so the state will colluding with private companies.

South Africa is in the process of building out a national database that will include the face of every resident and foreign visitor. One day, the government could track the movements of everyone in the country with the help of ABIS.

The real threat of activists, journalists, and business people being tracked illegally is not overstated.

NEC XON will always ensure that the use of facial recognition is done ethically.

Nkosi begins to count the cameras as we walk through Rosebank. There are seven on one pole. There are three people across the street. Six on another.

“The state may not be awake to it right now, but we’re heading there,” he says back in his home. “The spaces [for activism and protest] are going to shrink. Private companies are going to make a killing.”