Richard Pollard arrived to work at the University of the South Pacific in March 1986 and it was a beautiful day.

He found a padded envelope on the way to his office. There was an airmail sticker and a postmark from England.

A VHS videocassette and a letter were inside. In the Milk Cup, the tapes contained recordings of the matches between Watford and Chelsea in the First Division. The letter was from Graham Taylor, who asked for the cassette to be returned to England.

In the 1980s, a top-level English club used the only tape recording of a game to carry out match analysis, and then returned the analysis over a year later.

Pollard was interested in football data for over two decades. He had read the earliest published works of Charles Reep, who was seen by some as the originator of modern football analysis.

Reep was the first data analyst to work for a professional football club and later found great success with Wolves.

Pollard was inspired by Reep's work to visit his home in the UK, a pilgrimage that involved long afternoons of tea, sandwiches and football discussion.

Reep had hundreds of matches worth of data by the time Pollard visited in the mid-1960s. He kept a lot of handwritten notes, typed out formulas and large boards in his front room.

Reep's technique allowed him to combine data for each team in real time. He had to do everything by hand. He would spend 80 hours working on a chart from his notes from the World Cup final. Pollard would soon be able to work faster.

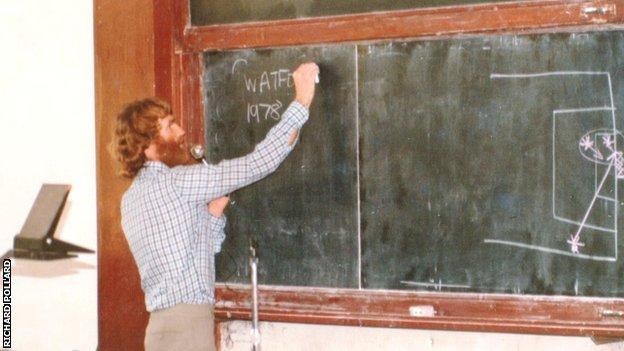

Pollard got a degree in applied computer science when the computer revolution started. I realized that Reep's data could only be analyzed on a computer.

The University of London used the Atlas 1 computer in Gordon Square from 1964 to 1972 and it is now located at the Science Museum. The computer was hidden within a windowless concrete building. Students rarely saw it in action.

If you needed to use the Atlas machine, you would punch a series of cards, drop them at reception and return the next day to pick up your results. Pollard was the first person to use a computer to analyze a football match.

Pollard received a summary performance data for 100 matches. There were a total of 13,600 values.

The initial aim of the analysis was to show the distribution of values for each of the variables.

Early results were not conclusive. Pollard went to university in Brazil for two years.

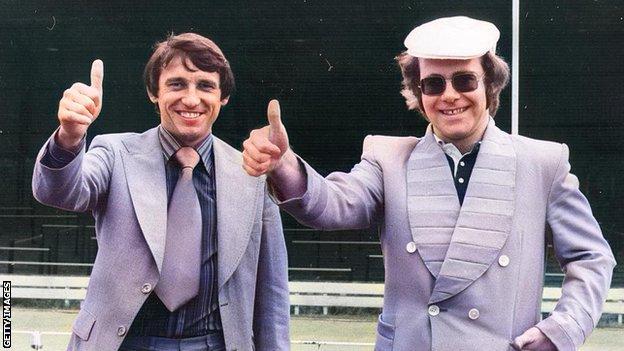

He bought a house about a mile from Graham Taylor when he returned to England in 1975. Things took off now.

Pollard put them in touch after he realized that Taylor liked to use an all-out attacking style similar to that of Reep. Pollard was able to analyse games during the 1980-81 season when the Hornets finished ninth in the Second Division.

Pollard recalls the second game he recorded, whenWatford beatSouthampton in the League Cup.

The first leg was won bySouthampton but the second leg was won byWatford. The European Cup holders were beaten by them in a subsequent round. Another night of nights as Reep called it.

Pollard worked with Reep to monitor a wide range of metrics. The number of times a team managed to pass the ball into the attacking third was the key measure. A throw-in, corner, or free-kick is astatic. The number of times a team won the ball back in the attacking third through pressing was measured.

The measures are important in winning football matches and form the basis of modern analysis. 40 years ago, Pollard was doing this.

He moved to a university job in Fiji, where he continued his football analysis in his spare time, providing in-game statistics for local radio and writing a column.

In the 1985 Fijian Cup final, he said that it would take more than penalties to separate the two teams. The game was declared a draw after darkness fell and the penalties were tied.

Pollard's work permit at the university didn't allow him to be paid for any outside work, so his newspaper editor would assign him to games on the far side of the islands and pay generous expenses.

I used to take the whole family in our little Suzuki Jeep on these free long weekends in hotels on the beach.

I used to tell the editor that his readers were better informed about football than anywhere else in the world.

There was no television coverage in the country. My father used to send me World Cup video recordings from England and I could replay them in the video lab as many times as I wanted.

Access to video footage gave analysts new opportunities. More aspects of the game were allowed to be investigated. Pollard found that when they had more defenders back in the penalty area, the Hornets conceded more attempts at their goal.

He was able to accurately note the position of each attempt at goal. In January 1986, he wrote a letter to Taylor. Pollard wrote a paper titled Soccer Performance Analysis and its Application to Shots at Goal at the University of the South Pacific. The expected goals metric flourished from the seed.

Pollard used data from different divisions of English football between the late 1950s and 1980s, as well as the 1982 World Cup and the North American Soccer League. Similar results were found across the leagues and decades in the 20,000 shots included in the study.

The goal-to-shot ratio was in the range of 8.2 to 10.6 and between 9% and 13% of all shots produced a goal. The distribution of shots attempted from inside and outside the penalty area yielded further insights.

The success rate from outside the box dipped to 3% while the success rate from inside the area was 15%. 40 years ago, such figures were new to analysts.

Pollard continued to work on shot locations, but his association with Taylor ended.

Pollard left his job at the university to go to the United States without a job because of a military coup in the country.

He eventually became England manager. In 1994 Norway defeated his side 2-0 in a World Cup qualification game and had another Reep-disciple at the helm, Egil Olsen. The Norwegian Football Association invited Reep to the game.

Pollard settled in California and came up with a method of ranking national teams that was rejected by Fifa but seems to give more accurate results. He advised Bhutan on how to improve their ranking in order to move up 40 places in the process.

Some people think expected goals are the go-to metric for assessing a side's long-term success. The underlying figures could give a better chance of judging a team's overall performance than actual results.

Pollard was at the center of this revolution as well as much of the history of football analysis.