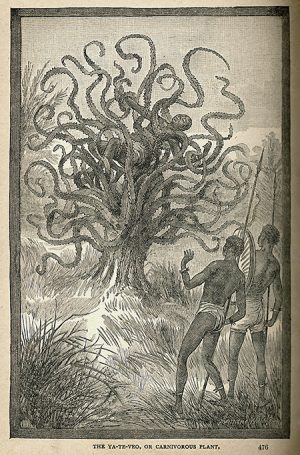

The tales of killer plants began to appear at the end of the 19th century. In far-off lands, trees snatched and swallowed travelers. Mad professors ate the monstrous sundews and pitcher plants they raised on raw steak.

A yarn featuring the Venus flytrap was used by the young Arthur Conan Doyle. He accurately described the two-lobed traps, how they captured insects, and how thoroughly they digest their prey. His flytraps were large enough to kill a human. Meat-eating, man-eating plants were having a moment, and for that you can thank Charles Darwin.

Most people didn't believe that plants ate animals. It was against the natural order of things. If animals killed plants, it must have been in self-defense or by accident. 16 years later, Darwin's experiments proved wrong. He showed that the leaves of some plants had been transformed into structures that could be used to trap and digest insects and other small creatures.

Darwin published Insectivorous Plants in 1875. The Power of movement in Plants was published in 1880. The realization that plants could move as well as kill inspired not just a hugely popular genre of horror stories but also generations of biologists eager to understand plants with such unlikely habits.

Researchers are starting to get answers to one of the great mysteries of the plant world, how did mild-mannered flowering plants evolve into murderers?

Advertisement

Researchers have been able to understand how a flytrap snaps so fast, and how it becomes an insect-juicing device. The big question remained, how did evolution equip these mavericks with the means to eat meat?

Almost no clues have been provided by fossils. A biophysicist at the University of WFC;rzburg in Germany says that there are very few fossils and that they can show details that might hint at an explanation. Researchers can now look for genes linked to carnivory, find out when and where those genes are switched on, and trace their origins with the help of new technology.

According to Hedrich, there is no evidence that the genes of the plant's victims were used to acquire its beastly habits. The co-option and repurposing of existing genes that have age-old functions is what the recent findings point to.

Evolution is flexible. Victor Albert is a plant-genome biologist at the University at Buffalo.