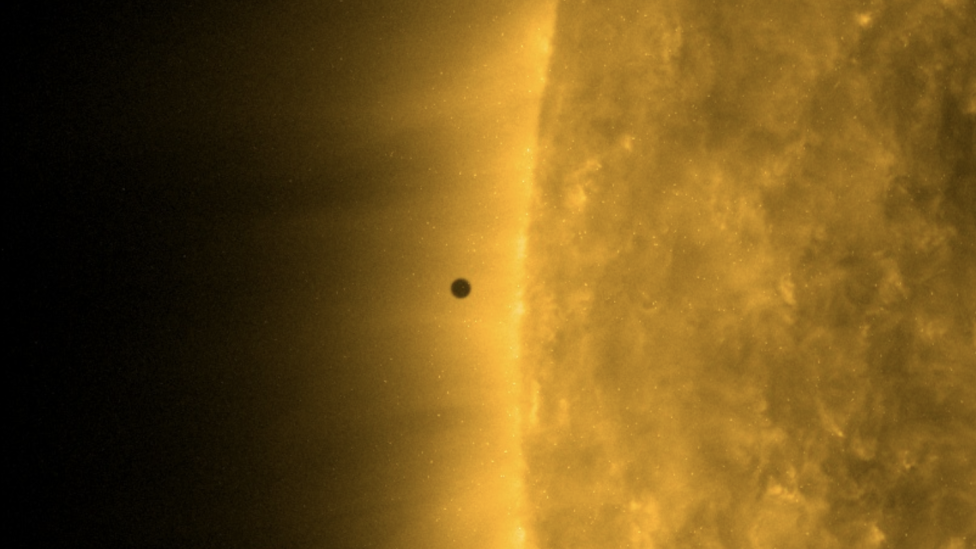

A huge wave from the sun smashed into Mercury on Tuesday, triggering a storm that likely scoured material from the planet's surface.

A powerful eruption, known as a coronal mass ejection, was seen from the far side of the sun on the evening of April 11 and took less than a day to hit the closest planet to our star.

There are areas on the outside of the sun where powerful magnetic fields are created by the flow of electric charges. The energy from this snapping process is released in the form of radiation bursts called solar flares.

Scientists say the coronal mass ejection will hit Earth at nearly 2 million mph.

Powerful geomagnetic storms can be triggered on planets with strong magnetic fields. During these storms, the magnetic field on Earth gets compressed by the waves of highly energetic particles, which trickle down magnetic-field lines near the poles and release energy in the form of light to create colorfulAuroras in the night sky. Scientists have warned that the movement of these particles could cause powerful magnetic fields to send satellites tumbling to Earth, and that these storms could cripple the internet.

Mercury does not have a strong magnetic field. It has been stripped of any permanent atmosphere due to its close proximity to our star. The comet-like tail of ejected material behind the planet is caused by the atoms that remain on Mercury being lost to space.

The solar wind, the constant stream of charged particles, the nuclei of elements such as carbon, nitrogen, neon and magnesium, and the tidal waves of particles from the sun replenish Mercury's tiny quantities of atoms.

Scientists were unsure if Mercury had enough strength in its magnetic field to cause storms. The magnetic field is strong enough, according to research published in two papers in February. The first paper showed that Mercury has a ring current, a doughnut-shaped stream of charged particles flowing around a field line between the planet's poles, and the second showed it was capable of triggering storms.

The processes on Earth are similar to those on other planets, according to a statement from a co-author.

The sun has been increasing its activity much faster than the official forecasts have predicted. The mechanism that drives this solar cycle isn't well understood so it's challenging for scientists to predict its exact length and strength

It was originally published on Live Science.