Clouds come in a variety of shapes, sizes and types. The University of Washington led a new research that shows how ice shards in Southern Ocean clouds affect the ability to reflect sunlight back to space.

The ice-splintering process improves the ability of high-resolution global models to mimic clouds over the Southern Ocean, according to a paper published in the open-access journal AGU Advances.

Lead author Rachel Atlas said that Southern Ocean low clouds shouldn't be treated as liquid clouds.

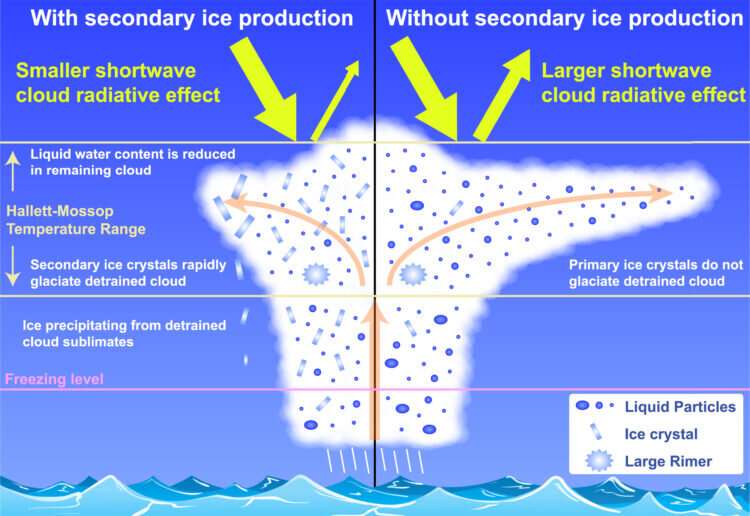

The results show that it is important to include the process whereby icy particles collide with supercooled droplets of water causing them to freeze and then shatter, forming many more shards of ice. Doing so makes the clouds dimmer or decreases the amount of sunlight that reaches the ocean's surface.

10 watt per square meter is enough energy to have a significant effect on the temperature in the summer, which is between 45 degrees south and 65 degrees south.

The study used observations from a field campaign that flew through clouds in the Southern Ocean, as well as data from two satellites.

The ice particles form, grow and fall out of the cloud very efficiently.

Atlas said that the ice crystals deplete much of the thinner cloud. The ice particles reduce the cloud cover.

In the summer season in the Southern Ocean in February, most of the skies are covered with clouds, and at least 25% of them are affected by ice formation. It's important to get the clouds right in the new models that use smaller grid spacing to include clouds and storms.

The Southern Ocean is a massive global heat sink, but its ability to take heat from the atmosphere depends on the temperature structure of the upper ocean.

Chris Bretherton is a professor at the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence in Seattle and is one of the co-authors of the study.

More information: R. L. Atlas et al, Hallett‐Mossop Rime Splintering Dims Cumulus Clouds Over the Southern Ocean: New Insight From Nudged Global Storm‐Resolving Simulations, AGU Advances (2022). DOI: 10.1029/2021AV000454 Journal information: AGU Advances Citation: Ice shards in Antarctic clouds let more solar energy reach Earth's surface (2022, April 13) retrieved 13 April 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2022-04-ice-shards-antarctic-clouds-solar.html This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.