Braniff International was a major player in US airline transportation from 1930 to 1982. After WW2 the airline won a South American route award and carved out a niche in Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas. Braniff International became a US major after mergers with Mid-Continent Airlines of Kansas City and Pan American Grace.

Braniff International caught the attention of the travelling public with a radical image makeover in 1967, steered by advertising executive Mary Wells: The End Of The Plain Plane. The red and blue cheatline was replaced by a striking new livery in which every plane was painted a different bold colour with white wings. At Dallas Love Field airport, the colour schemes were used for lounges, ticket offices, ground equipment, and even the Jetrail monorail. The art was flown in from Mexico and South America. Italian fashion designer Emilio Pucci created new uniforms, and Mexican architect Alexander Girard created a furniture line for offices and lounges, which was made available to the public for a year. The airline's base became a hub after the brand refresh and the move to the Dallas/Fort Worth mega-airport.

Braniff had Texan swagger for bigger, better, brighter bolder. In 1964, the airline placed an initial order for the home-grown swing-wing Mach 3 SST, the Boeing 2707, going so far as to make industrial films explaining the supersonic future that awaits America in the skies. The programme was canceled by Congress in 1971 because it was too expensive to take flight.

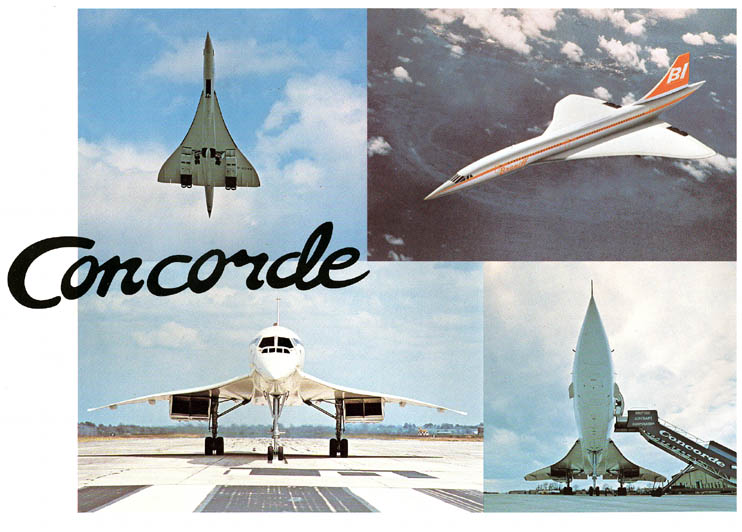

The British and French created a European SST called the Concorde. Braniff secured delivery positions for three Concordes in the late 1960s despite being smaller (100 seats vs 277 seats) and slower Mach 2 vs Mach 2.7. British Airways and Air France, the flag carriers of the two nations that created this miracle plane, were the only ones who could convert those options to firm sales.

On January 21, 1976, Concorde went into revenue service with British Airways and Air France. The European SST was banned from US skies due to citizen protests against aircraft noise, but the market that best suited was across the Atlantic to the US.

Concorde’s first flight – fifty years ago

British Airways and Air France opened service from their respective hubs on May 24, 1976, after US Secretary of Transportation William Coleman granted Concorde access to Dulles airport, 26 miles west of Washington DC in rural Virginia. Concorde flights were banned in New York until October 17, 1977 after the Supreme Court overturned a lower court ruling, but the grand prize remained New York's John F Kennedy airport. On November 22, 1977, supersonic service to The Big Apple began.

This was a good time to be optimistic about the Concorde project. British Airways painted one of its planes G-BoAD, which means "friend" in Arabic, and opened a service to Singapore via Bahrain with BA pilots and 50/50 BA-S.

The Singapore service only lasted three rotation due to complaints from the government of Malaysia about sonic booms in the Straits of Malacca, but G-BoAD retained the Singapore livery on its left side and was able to return to Singapore on January 24, 1979.

Braniff International ideas, whose ardour for supersonic flight hadn't entirely cooled after the disappointment of the B2707 and its own early Concorde ambitions, was helped by the Singapore Airlines partnership. Routes to Latin and South America are celebrated by the famous "flying artwork" of the DC-8 painted by Alexander Calder.

Flying the British/Singapore Air Concorde in 1980

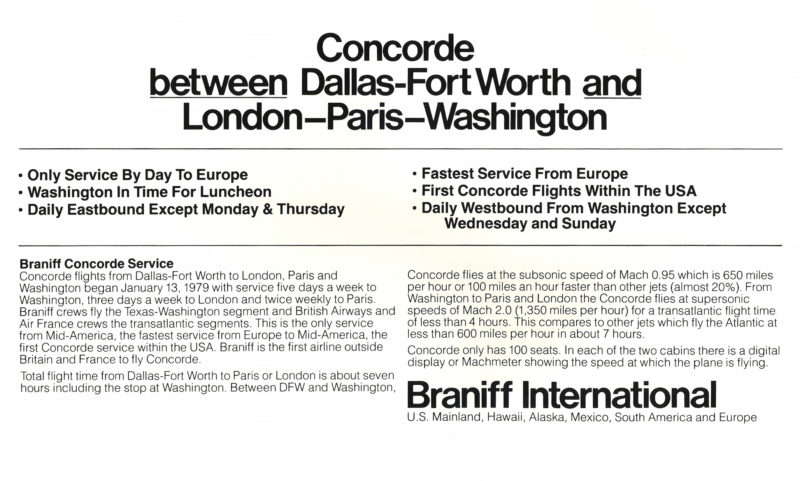

In lieu of ownership, a concept emerged for domestic Concorde services in the United States to be operated by both British Airways and Air France planes, fresh in from the Atlantic, on the 1,172 mile (1,886 kilometer) route from Washington to Braniff's home base. The aircraft would return to Washington the next morning after a night stop. The Braniff flights would be with Braniff crews; the exterior identity of the aircraft would depend on the day of the week.

The only downside was that it couldn't operate supersonic due to the inability to mitigate the sonic boom, but cruising at a high Mach number would still shave 20 minutes off the journey compared to a flight aboard.

The plan was helpful. Washington flights struggled to make money for both British Airways and Air France, so hopefully this would create some feed for the transatlantic legs, as that route was opened by Air France in September 1978 with this intention.

Concorde didn't find any airline customers outside the borders of the countries that created her. Braniff International could be claimed to exist with some marketing sleight of hand.

Braniff could offer a unique product, the excitement of flying on an SST, in a crucial period when making a big splash was vital, slugging it out with American and Delta in a never-ending turf war at Dallas/Fort Worth.

A total of 14 Braniff pilots were trained in France and the United Kingdom. Those trained by Air France did their course at Toulouse, followed by circuits on a real aircraft at Shannon, and those trained by British Airways did their course at Filton in Bristol. Braniff crews were fully trained to operate at speeds of up to Mach 2.2, even though their initial plans were all over land.

British and French pilots retired at 55, but in the United States it was 60, which meant that a few Braniff pilots who flew the Concorde would not have been able to do so in Europe.

Braniff was unable to operate a foreign-owned and foreign- registered aircraft within the US, so the Concorde's ownership was transferred to Braniff on arrival at Washington. British Airways and Air France gave their planes new custom registration to make a daily transfer to the US register.

Braniff ground crew in Washington could tape over G-N94AA to create it. For the whole fleet, G-N94AB became G-N94AF and so on. The only exception to the 94 series was G-BOAC. Air France adopted a similar practice, with F-BVFA becoming F-N94FA and thus N94FA.

The British or French documents certifying ownership, registration, and airworthiness were to be removed from the cockpit during the Washington turnaround and placed in a special compartment in the forward toilet, while the US documents temporarily took their place up front for the trip to Texas.

The onboard product was five ounces of Chateaubriand steaks and five ounces of champagne. In first class on subsonic Braniff flights, the addition of dry ice smoking from the aperitifs trolley could not be done because of the confines of the Concorde cabin. The fare for the experience of flying on an SST was a flat $220 one way, ten percent higher than a regular first class ticket.

A tour of Braniff ports was operated by a British Airways Concorde, and it was used to promote the new service. While British Airways and Air France expanded their charter operations in the 1980s and 1990s and visited some obscure ports with their rocket ships, the Braniff promo tour was their only Concorde visit.

The first domestic commercial SST flights took place in the United States. Two Concordes were positioned the day before. After a ceremony in the Texan winter morning in front of terminal 2W, Braniff Captain Glenn Shoop commanded N94AE and N94AC to leave under his command.

There were five trips a week after that. Picking up an Air France Concorde at Washington, inbound from Paris, BN53 operated from the nation's capital on Mondays and Fridays at 1910, landing in Dallas at 2200. On Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, a British Airways machine left Washington at 1840 and arrived in Dallas at 2030.

The aircraft would fly back to Washington the next day after a night stop in Dallas. On Tuesdays and Saturdays, BN54 leaves at 0930 and arrives in Washington at 1300, while BN188 leaves at 0830 and arrives in Washington at 1200.

Braniff started flying their signature Big Orange from Dallas to London on March 18, 1978, so once the British Airways Concorde interchange started, Braniff could boast of near-double daily service.

Concordes with a maroon cheatline and logo did not receive Braniff livery. If one had been painted, it would have been on the other side, like G-BoAD, which provided free advertising for Singapore Airlines on its starboard side in the course of its Braniff flights before their own services reached the United States.

This unique product failed to catch on with the American public. Concordes had a cramped interior, which only allowed economy-style 2-2 seating, compared to the more spacious first-class quarters of a Boeing. The 20 minutes saved by cruising at a higher Mach number was not worth it. After the first few weeks, the loads were usually as low as 20 passengers per flight.

The Braniff experiment was a red herring in Concorde's search for a sustainable supersonic business model. Braniff might have bought Concordes for service to South America if the economy had been stronger and the market had reacted differently.

One important question remains before the story ends. Braniff flights may have gone through the sound barrier. It isn't considered controversial to suggest that most pilots and passengers joined the supersonic club for a few seconds or minutes over Tennessee or Arkansas. Wouldn't you?

The airline had no choice but to bow to the inevitable, with passenger numbers showing no sign of breaking even. On June 1, 1980, the supersonic era on domestic flights in the United States ended.

In October 1982, Air France pulled its Concorde service from Washington, while British Airways added a new route to Miami in March 1984, but only for international passengers to book. Washington and Miami ended in the same year.

In June 1988 British Airways added a second tag from Washington to Dallas, which was only bookable for international passengers. The route was axed after only four months after passenger numbers weren't any better the second time around.

After the Concorde experiment, Braniff International only lasted a few more years. While the 1970s had seen success and style in equal measure, the scale of the airline's expansion at the dawn of deregulation was too much to handle. The airline made headlines around the world when it ceased operations in 1982.

The cabin crew of Concorde flights would take leftovers home and feed them to their cats if Braniff hadn't failed. Robert Crandall at American Airlines was applying computer power and forensic analysis to manage yield and weaponise the AAdvantage frequent flier programme while he was occupied with such pie-in-the-sky ideas as subsonic Concorde flights and half-empty bright orange 747s to Singapore. The outcome of the Battle of DFW was never in doubt.

Braniff was able to provide the American travelling public with the excitement and prestige of flying on an SST because of a complex arrangement with two European airlines. It didn't happen because it didn't last. The colors will always be flying.