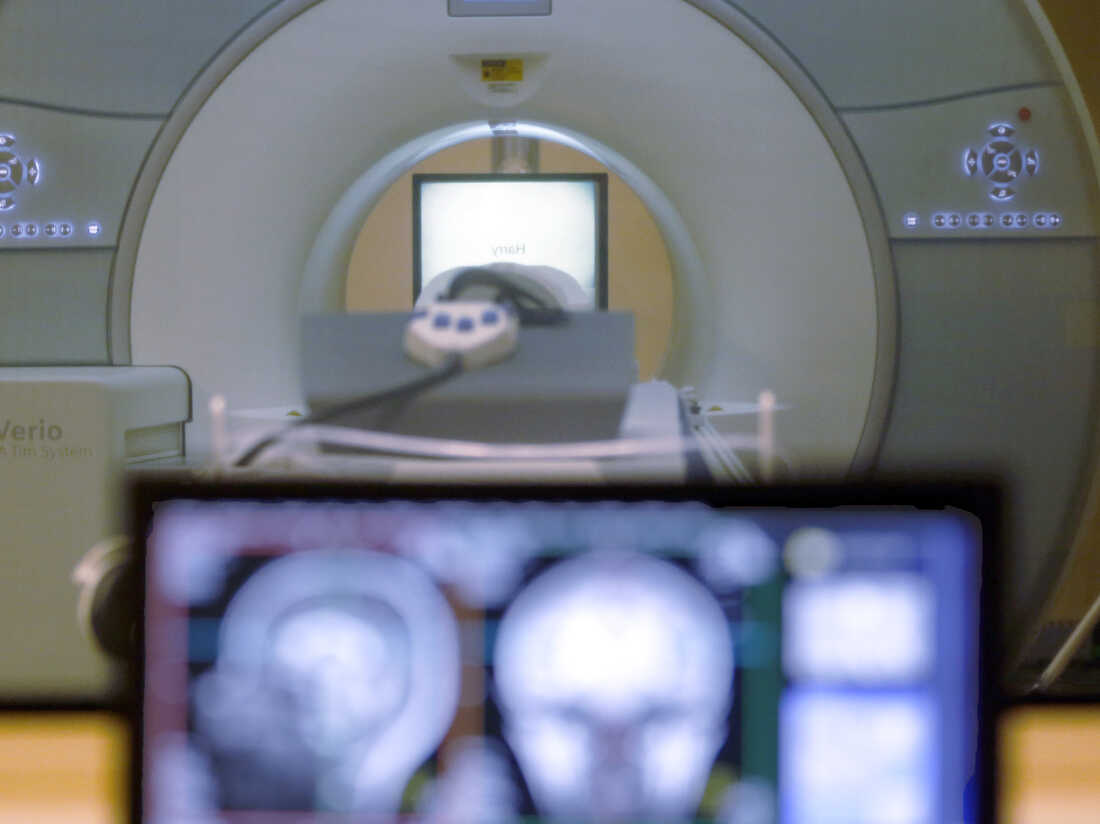

Scientists analyzed a huge number of brain scans to learn more about how the brain develops from infancy to the end of life.

Keith Srakocic/APThe human brain begins with a bang and ends with a whimper.

A project that used more than 120,000 brain scans to chart the organ's changes throughout the lifespan is over. The results are in the April 6 issue of Nature.

The key findings are listed.

The study could eventually lead to brain growth charts that would allow doctors to look for atypical development in young patients. For now, the results are meant for scientists who study typical brain growth or brain disorders.

One goal is to use this huge amount of existing data to help understand and treat psychiatric diseases, according to one of the study's authors.

The project began more than six years ago when two young researchers at a scientific conference began talking about a simple question.

They realized there was no good answer because most studies that involved brain scans had been limited to a small group of people. The studies kept their data in different forms and used different designs.

The researchers had an idea.

Richard Bethlehem is a research associate in the psychiatry department at the University of Cambridge.

The University of Pennsylvania and Children's Hospital of Philadelphia began asking other researchers if they would contribute their study data to the effort.

Everyone came back and said, "This looks great, we should definitely be doing this."

The pair assembled an international team and began the hard work of turning more than 100 small studies into one big one.

Richard and I spent a lot of time selecting the data sets.

More than 100,000 people had their brain scans, ranging from a fetus to a centenarian. They realized how different brains were when they analyzed the data.

The sheer variability of how big the brain gets throughout development is one of the fundamental things that we started to see.

The team found that there were different growth patterns in different areas of the brain and in the volume of white matter, gray matter, and subcortical gray matter.

The study still has gaps, including a lack of racial and ethnic diversity.