The molecule produced by male worms called schistosomes that prompt sexual maturity in females of these species has been identified by a team led by UTSW researchers. The findings, reported in Cell, help answer a century-old mystery and could lead to new treatments for a tropical disease that kills up to 200,000 people a year.

The study leader said that schistosomiasis keeps poor people poor by preventing them from living up to their full potential.

The WHO estimates that 220 million people have the disease. The life cycle of the flatworm parasites is complicated and involves stages in both freshwater and mammals. Schistosomes feed on blood and lay lots of eggs, which lodge in tissues and organs and cause symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloody stool, and blood in the urine.

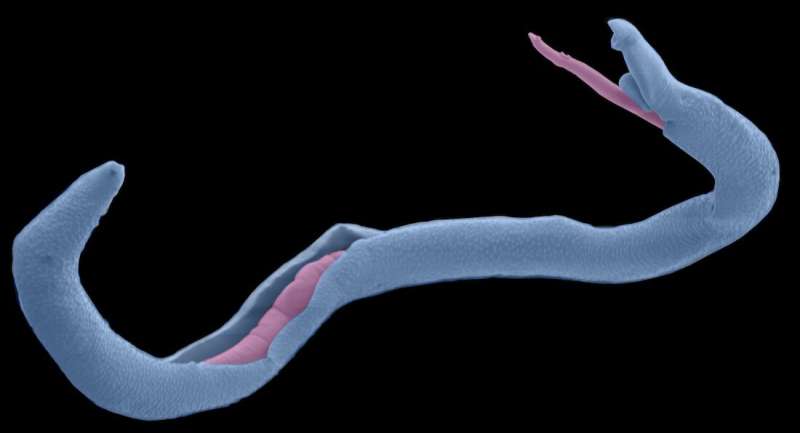

Unlike most flatworm species, schistosomes have male and female sexes. Researchers discovered nearly a century ago that females must be in physical contact with males to become sexually mature and to lay the eggs that cause schistosomiasis. The mechanism behind this route to puberty is unknown.

When male and female schistosomes came into contact, graduate student Rui Chen, Jipeng Wang, and their colleagues searched for changes in gene activity. They discovered that a gene called gli1 was important in males to prompt female sexual maturity. When the researchers deleted gli1 in males, the females never laid eggs.

The researchers sought out genes that were directed by gli1 in males that could be key for female sexual maturity because gli1 is a transcription factor. The Schistosoma mansoni nonribosomal peptide synthesise (Sm-nrps) was identified through their search. After showing that Sm-nrps in males is essential for launching and maintaining sexual maturity in females, further research showed that the key product made by this gene is a small peptide called b-alanyl-tryptamine. Even without a male present, dosing female schistosomes with just that peptide was enough to start and continue sexual maturity.

Dr. Collins said that blocking any part of the pathway that leads to schistosome eggs could offer a new way to fight the disease. Although many animals have genes similar to Sm-nrps, none have been reported to have roles in chemical signaling, suggesting the discovery of a previously unrecognized type of communication between animals. Dr. Collins said that he and his colleagues plan to look for similar pathways in other animals.

More information: Rui Chen et al, A male-derived nonribosomal peptide pheromone controls female schistosome development, Cell (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.03.017 Journal information: Cell Citation: Discovery provides insight into neglected tropical disease schistosomiasis (2022, April 6) retrieved 6 April 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2022-04-discovery-insight-neglected-tropical-disease.html This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.