Even though the instrument stopped operating four years ago, NASA's Kepler space telescope spotted a Jupiter look-alike.

An international team of astrophysicists using NASA's Kepler space telescope have discovered an exoplanet similar to Jupiter located 17,000 light-years from Earth, making it the farthest exoplanet ever found by the telescope. The exoplanet K2-2016-BLG-0005Lb was spotted in the data captured by Kepler. Over 2,700 now-confirmed planets were observed by the program.

Eamonn Kerins, an astronomer at the University of Manchester in the U.K., was able to determine precisely the mass of the exoplanet and its host star with the help of the weather or daylight.

The strangest alien planets are in the gallery.

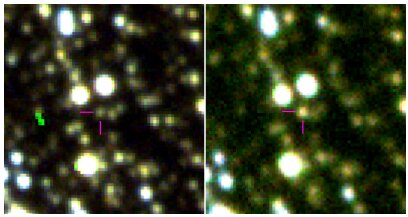

David Specht is a PhD student at the University of Manchester. The light from a background star is warped and magnified by the gravity of a larger object, which was predicted by Einstein.

The team used three months of observations from the telescope to try and find an exoplanet.

It takes almost perfect alignment between the foreground planetary system and a background star to see the effect. There are hundreds of millions of stars in the center of our universe. So he sat and watched them for three months.

Iain McDonald, an astronomer at the University of Manchester, developed a new search algorithm for the team. They were able to reveal five candidates in the data, with one clearly showing signs of an exoplanet. Other ground-based observations of the same stretch of sky corroborate the signals that were seen by the telescope.

The difference in vantage point between the two allowed us to triangulate where the planetary system is located.

The team's work is notable because it was not designed to discover exoplanets using this phenomenon. In 2016 the mission was extended. After two reaction wheel failures, it was proposed that the K2 second light mission would see the scope detecting potentially habitable exoplanets. The mission was extended way past the expected end date until it ran out of fuel in October.

Kerins said that it is amazing that it has done so, since it was never designed to find planets using microlensing.

Roman and Euclid will be better for this kind of work. They will be able to complete the planet census. We can use the data to test our ideas of how planets form. This is the beginning of a new chapter in our search for other worlds.

This discovery was described in a study posted on ArXiv.org and has been submitted for publication in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

If you want to follow her, email her at cgohd@space.com. Follow us on social media.