Researchers were absent from the nation's airwaves when I set up the Science Media Centre. Most scientists put their heads down and tried to avoid controversy, even though they had to deal with a lot of frenzies in the media. The price was the British public's rejection of GM technologies and low levels of MMR vaccinations.

It is not enough for researchers to do great science, they need to communicate its implications. Most of the UK's science news is translated by our outstanding science correspondents.

When government press teams get involved, the rule has a key exception. They are now in charge of UK science communication. Civil servants often take up reports about research done in universities and far-off research institutes because these projects are funded indirectly by the government. Some examples include research on badgers and Covid-19's prevalence.

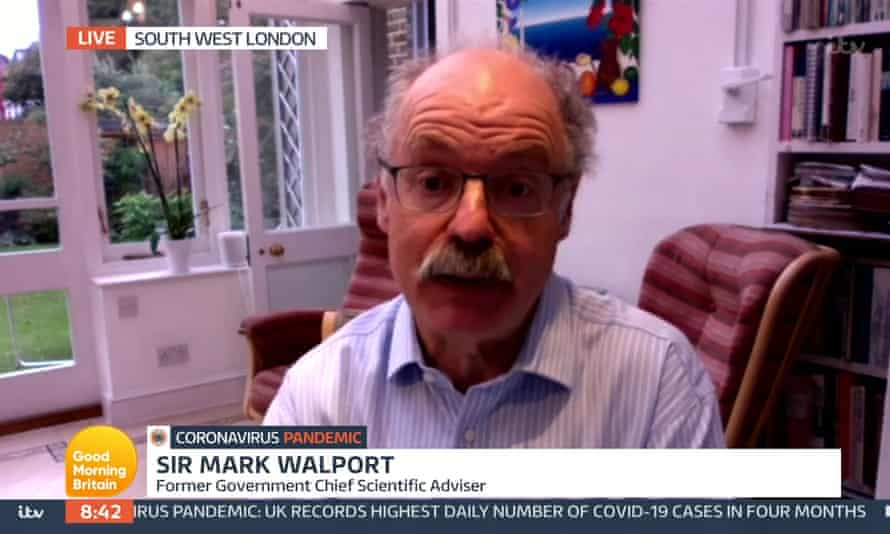

The creation of UK Research and Innovation has made the problem worse. The agencies were combined into one body. The move gave science a voice at No 10 and the Treasury but has also resulted in scientists losing independence and their own voice, a trend lamented by the organisation's founding CEO, Sir Mark Walport.

Major Covid studies, which were carried out at universities, were commissioned by government departments and involved scientists working with the public. A communications system designed for publicising the government's ideas also got swept up in the scientific data. I was approached several times by government comms experts frustrated by the mixed messages coming from senior scientists who spoke openly about the uncertainties and gaps in our knowledge on everything from mask-wearing to the risks of school kids driving transmission. How could they stop this?

They were asking the wrong person. I argued that messaging is for politicians, and that it would endanger public trust in science at a critical time. There was no science on Covid.

The land-grab for science communication has occasionally taken a more sinister turn in the form of proposals such as changes to the civil service code which would prevent any government funded scientist from speaking to the media without the permission of the minister.

The fact that people were working on such policies should remind us that vigilance is important. Sue Gray, a previously unheard of civil servant, agreed to change the wording of purdah rules designed to restrict civil servants from speaking out in the run-up to elections when it became clear that over-enthusiastic government press officers were urging academic scientists to keep silent before polling day. The rules were never intended to apply to the daily media work of academics.

There is a precedent for freeing science from the government's communications machine. The H arding Prize for Useful and Trustworthy Communication was awarded to the Office for National Statistics. The judges pointed out that the data was free from spin.

This independence was not a product of the ONS boldness. The way national statistics were spun to the media by successive governments led to growing pressure to change the system. The principle that official statistics should be communicated separately from government was the subject of an influential Royal Statistical Society report.

We need to treat scientific data gathered outside of the government the same way we do official statistics. The public trust in government would be enhanced if the reins were loosened. It is the right thing to do and would be a fitting legacy of the Pandemic.

Beyond the Hype: The Inside Story of Science's Biggest Media Controversies will be published on 7 April.