NASA's Mars rover Perseverance has found that sound travels more slowly on the Red Planet than it does on Earth, and that it behaves in unexpected ways that could have strange consequences for communication on the planet.

Sound waves move more slowly on Mars than they do on Earth. It makes sense that the speed of sound depends on the density of the material that the sound waves are traveling through. Sound travels at a rate of 1,125 feet per second in the atmosphere, but in the water it moves at a rate of 4,856 feet per second.

The atmosphere on Mars is so thin that sound travels at just 800 feet per second.

A new study presented at the 53rd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference states that NASA's Perseverance rover has discovered some strange sounds on Mars.

Perseverance rover's Mars samples will not make it to Earth until 2033 at the earliest.

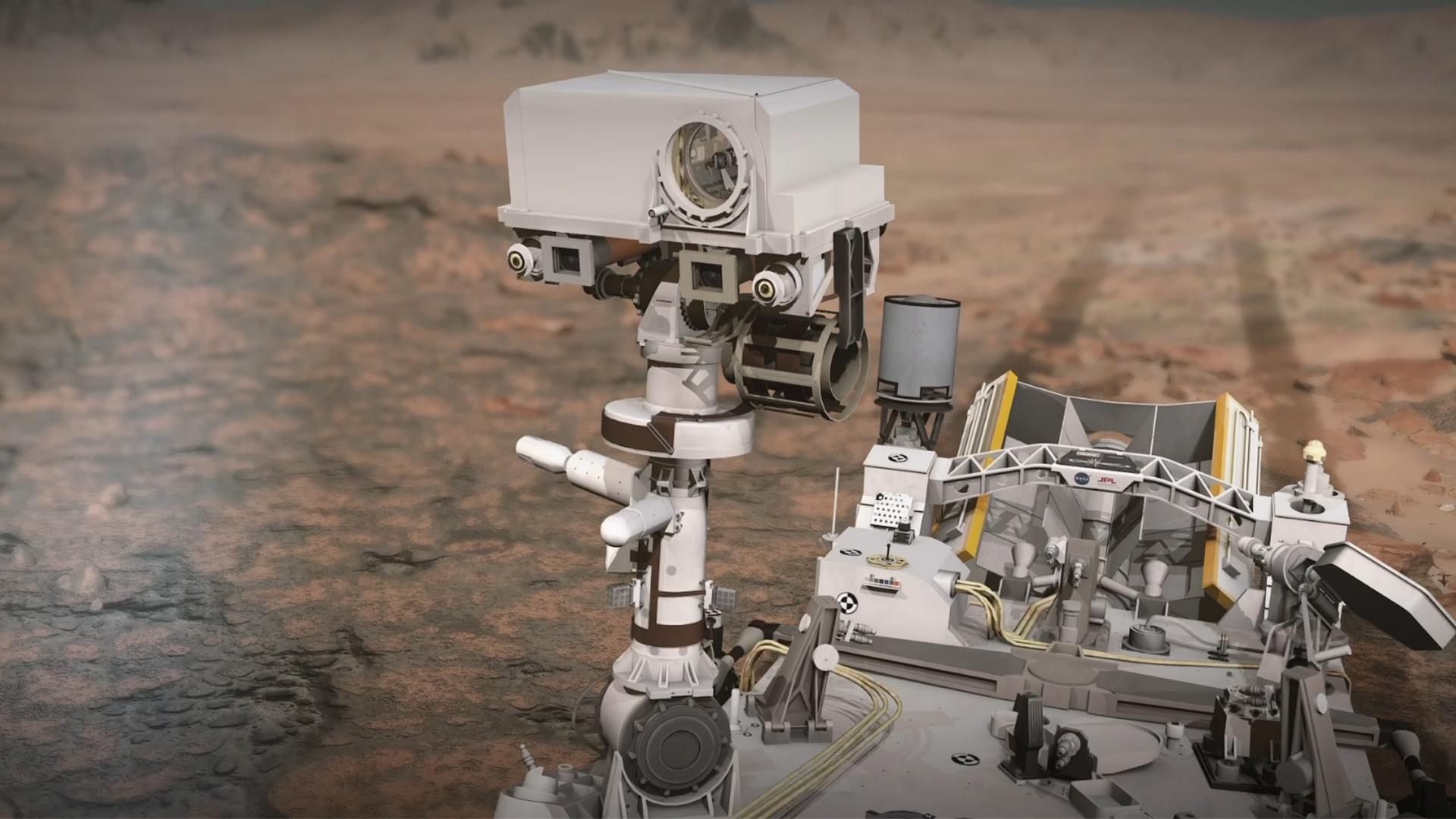

A team of scientists from Los Alamos National Laboratory used a microphone on Perseverance's SuperCam instrument to measure the speed of sound on Mars.

The scientists theorize that the strange behavior could be explained by thermal fluctuations in the first 6 miles of Mars' atmosphere. The Planetary Boundary Layer is a layer of Martian air caused by convective drafts and turbulence. That changes the behavior of carbon dioxide. The atmospheric pressure on Mars is very low. Earth's atmosphere contains only 0.041% of carbon dioxide.

Due to the unique properties of the carbon dioxide molecule at low pressure, Mars is the only planet in the solar system that has a change in sound speed in the middle of the bandwidth.

The researchers said that the carbon dioxide molecule does not have enough time to relax or return to its original state at higher frequencies.

If you were standing on Mars listening to distant music, you would hear higher-pitched sounds before you heard the lower-pitched ones.

The team plans to continue using SuperCam microphone data to observe how sound on Mars might be affected by daily and seasonal variations. They plan to compare acoustic temperature readings to readings from other instruments to figure out the large fluctuations, according to the statement in Science Alert.

The paper can be found on the website.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on social media. Follow us on social media.