In the summer of 1958, a 17-year-old Brazilian took international football by storm.

There were six goals in four games. There was a hat-trick in the semi-final. Brazil won the trophy they so desperately wanted.

Pelé was an unknown when he arrived in Sweden for the World Cup, but he went on to achieve sporting immortality. The man in the Brazil camp argued against him playing.

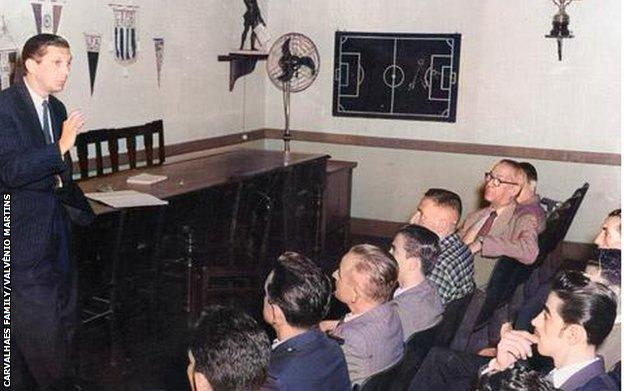

Professor Carvalhaes was the team's psychologist. He had real influence over selection, unlike his modern-day counterparts, who tend to be focused on supporting players and mental health.

The results of the psychometric tests Carvalhaes applied was the reason for his somewhat dubious advice. The legendary footballer said that Carvalhaes methods were either ahead of their time for football or just odd.

He is a sporting pioneer. The concept of psychology laboratories to South American football was introduced by Carvalhaes.

They wanted all the help they could get.

The World Cup campaigns of Brazil were torturous. In 1950, Brazil was mourning the loss of its spiritual home of football, the Maracan.

Brazil were reduced to nine men during a 4-2 loss to Hungary in the quarter-finals of the 1954.

While the national team tried to move on from the emotional trauma, a little-known psychologist was making his entrance into Brazilian football.

In 1957, Carvalhaes left a job training referees for the football federation to join São Paulo. The club was interested in the psychology laboratory he had founded, the likes of which would not be seen in Europe until the late 1980s.

10 tests examining cognitive functions were housed in the lab at the federation's headquarters. The tests were used by Carvalhaes to highlight the skills that would be needed to become a professional referee.

Candidates scoring below a benchmark considered unable to referee are set thresholds by Carvalhaes. Participants who recorded a result slower than 50 hundredths of a second during thereaction time test fell into this category.

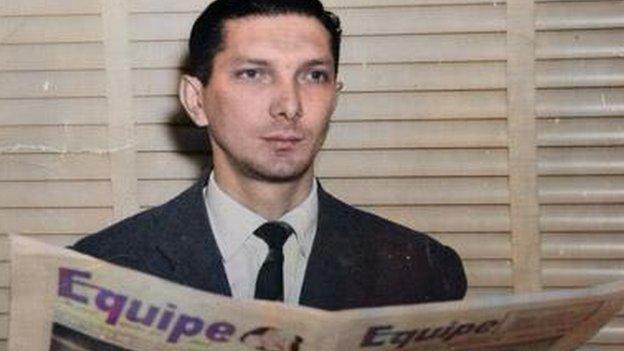

He used the name Joao of the Ring after combining his day job with regular evening stint as a boxing commentator and journalist. In contrast to his ringside persona, Carvalhaes' touchline demeanor was reflective according to his former colleague.

"Arriving at the training ground, you could see everyone excited, but João would be in the corner, quiet, hands in his pockets, just observing," he told a 2000 documentary on Carvalhaes' work, made by the São Paulo Regional Council of Psychology.

Carvalhaes was far from a mere observer.

Carvalhaes was hailed for his role in the selection decision that proved to be the key to victory after the team won the Campeonato Paulista in 1957.

The replacement of Ademar with Sarara was based on concerns about his state of mind, according to the club director.

The Brazilian Football Confederation came calling a year later. The man in charge of planning for the World Cup asked Carvalhaes to join the technical committee. The offer was too good to refuse.

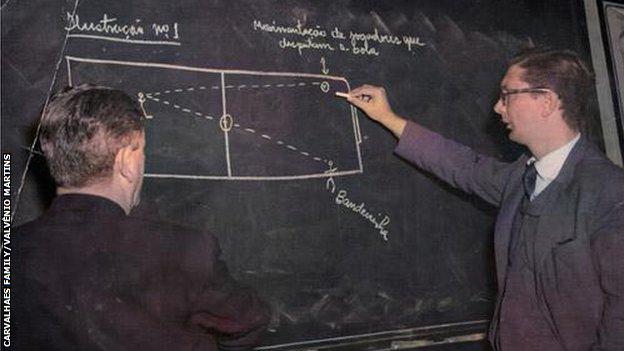

Carvalhaes wasted little time in implementing the methods he had used at São Paulo. During the squad's pre-tournament camp, he conducted an adaptation of an American programme designed to assess the intellectual capability of World War One recruits.

The 50-minute exam looked at players' ability to read and write. Those deemed less capable were asked to take a test that included exercises such as completing half-drawn pictures and tracing paths through two-dimensional mazes.

The tests pushed the boundaries of thinking at the time, particularly in a sport that had seen very little, if anything, in the way of psychology-focused interventions.

The CBF technical committee asked Carvalhaes to present his findings. He was upset that the results were leaked to the Brazilian media. Carvalhaes wrote a letter to de Carvalho saying that his documents were stolen.

Garrincha, who had poor test results, was thought to have failed to make the cut for the World Cup. Carvalhaes was angry. His behind-the-scenes way of working was disrupted by the public backlash.

The storm was short-lived. After Garrincha was named in Brazil's squad, media speculation died down and Carvalhaes went to Sweden with the rest of the backroom staff. He continued to work with the players, using Myokinetic Psychodiagnosis tests to analyse individual characteristics and tailor his support accordingly.

The theory behind the MKP tests is that if players are given a blank sheet of paper and asked to draw whatever they want, it will indicate their temperament.

Carvalhaes was applying techniques that had never been used before. He ran into trouble again.

The team psychologist conducted tests on all the players as part of the preparations, according to Pel.

We had to draw sketches of people and answer questions about whether we should be picked or not.

He concluded that I should not be selected. He was advised against Garrincha because he was not seen as responsible enough.

Vicente Feola, Brazil's manager, nodded gravely at the psychologist and said: "You may be right." You don't know anything about football. If Pel is ready, he plays.

Others were more positive.

Goalkeeper Gilmar said he gave them the chance to take on ideas that could improve their performance after the tournament.

The team learned to enter the pitch smiling, and Brazilian radio reports after the World Cup victory spoke of the importance of Carvalhaes.

The CBF was less forthcoming in commending him, a stance that took an emotional toll on a reflective individual.

He was upset because de Carvalho made inappropriate comments about his work.

He was starting to get more attention. According to Barella, Carvalhaes received interview invitations from magazines in Spain, France and Germany, as well as Sports Illustrated, which highlighted his contribution to the Brazil team.

Carvalhaes was helped by the international recognition. It may have paved the way for future leading practitioners, such as Dr Bruno Demichelis, AC Milan's venerated former sport scientist, to advance the use of psychology in elite football.

Two years after retiring, Carvalhaes died at the age of 58. After the World Cup, he stepped down from his national team position to return to his role at the club that helped make him famous.

Carvalhaes was able to introduce new ideas such as individual counseling sessions for players to supplement the cognitive testing that he was renowned for.

He worked for São Paulo until 1974 and provided psychological support for Brazilian fighters in the Pan American Games in 1963.

Coleman Griffith was the first sports psychologist, but his work was limited to American football. Carvalhaes was implementing methods that had never before been seen in top-level football.

If he played a role in laying the groundwork for modern sports psychology, the CBF would have lent a helping hand.

Without the risk taken in appointing a psychologist, who only worked for one season before joining the national team, it is likely that his work would not have been as well known.

Even though English clubs are mandated to provide psychological support for players at academy level, psychologists are still not commonplace.

"Psychology is accepted to various degrees within football clubs", says Simon Clifford, who led the sports science department at Saints in the early 2000s.

Some managers don't want their players to see a professional psychologist unless there is a problem, while others will have psychologists working closely with first-team players.

When clubs started to embrace strength and conditioning, it was like that. It took some time for the first team staff to trust the practitioners. We are still in the early days of psychology.

There will be a time when psychologists and coaching teams work together more smoothly, in part because of the influence a player's state of mind has on performance.

Even if some of Carvalhaes work could be seen as crude by current standards, there was still far-sightedness to it that you can see in the roots of today's sports science.

The role psychology plays in elite football is massive.

Bill Beswick once said that the mind is the athlete. The means of the body.