The inability to personally care for loved ones who have fallen ill is one of the most devastating elements of the coronaviruses epidemic.

Grieving relatives have testified many times that their loved one's death was more devastating because they were unable to hold their family member's hand in their final days and hours.

Some people had to say their final goodbyes through their phones. Others use walkie-talkies or wave through windows.

How do you come to terms with the thought of a loved one dying alone?

I have no answer to this question. Christopher Kerr is a doctor who co-authored the book Death Is But a Dream: Finding Hope and Meaning at Life.

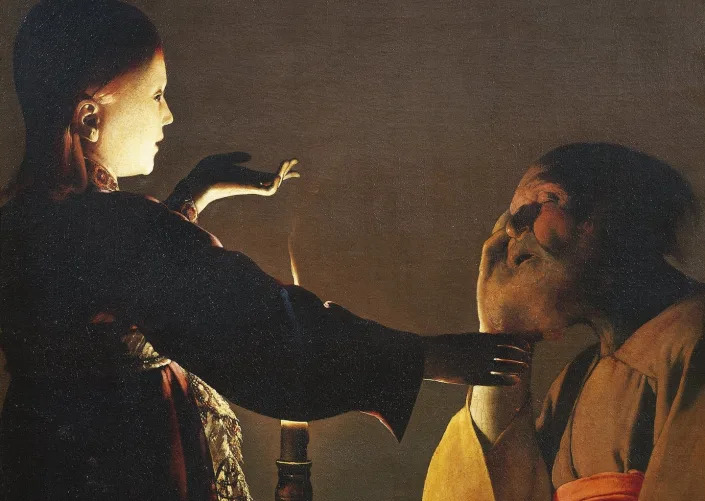

At the beginning of his career, Dr. Kerr was expected to attend to the physical care of his patients. He noticed that seasoned nurses were used to it. Many patients had dreams and visions of their dead loved ones who came to comfort them in their final days.

Doctors are trained to interpret these occurrences as drug-induced or delusional hallucinations that might warrant more medication or even a coma.

After seeing the peace and comfort these end-of-life experiences seemed to bring his patients, Dr. Kerr decided to pause and listen. One day in 2005, a dying patient named Mary had a vision in which she cooed at her child who had died in infancy decades prior.

This didn't seem like cognitive decline to Dr. Kerr. He wondered if the end of patients' lives mattered to their well-being in ways that should not be of concern to nurses, chaplains and social workers.

If all physicians stopped and listened, what would medical care look like?

At the sight of dying patients reaching out to their loved ones, many of whom they had not seen, touched or heard for decades, he began collecting and recording testimonies. Over the course of 10 years, he and his research team recorded the end-of-life experiences of 1,400 patients and families.

He was astounded by what he found. Over 80% of his patients had end-of-life experiences that were more than just strange dreams, no matter what walk of life, background or age group they came from. These were meaningful and vivid. Near death they always increased in frequencies.

They had visions of dead pets coming back to comfort their former owners, as well as long-lost mothers, fathers and relatives. They were about resurrection relationships, love and forgiveness. They provided reassurance and support.

I heard about Dr. Kerr's research in a barn.

I mucked my horse's stall. The stables were on Dr. Kerr's property, so we often discussed his work on the dreams and visions of his dying patients. He told me that he was working on a book project and that he was going to give a talk at the TEDx event.

I was moved by the work of this doctor and scientist. I offered to help when he said he was not getting far with the writing. At first, he hesitated. I was an English professor who was an expert in taking apart other people's stories. His agent was worried that I wouldn't be able to write in ways that were accessible to the public. The rest is history.

This collaboration turned me into a writer.

I was tasked with instilling more humanity into the medical intervention this scientific research represented, to put a human face on the statistical data that had already been published in medical journals.

The moving stories of Dr. Kerr's encounters with his patients and their families confirmed that he who should teach men to die would at the same time teach them to live.

I wassailed by conflicting feelings of guilt, despair and faith when I learned that Robert was losing Barbara, his wife of 60 years. He saw her reaching for the baby they had lost decades ago in a dream that was similar to Mary's. Robert was struck by his wife's smile and calm demeanor. They experienced a moment of pure completeness, one that changed their experience of dying. Seeing Barbara comforted brought Robert some peace in the midst of his irredeemable loss, as he was living her passing as a time of love regained.

Dr. Kerr cared for elderly couples who were separated by death. The deep wound left by her husband's passing was mended by her recurring dreams and visions. She would point out his presence during the day and at night when she was awake. These occurrences gave Lisa the knowledge that her parents' bond was not a thing of the past. Her mother's pre-death dreams and visions helped Lisa in her own journey toward acceptance.

Pets that are dead make appearances when children are dying. Jessica had visions of her former dog, Shadow, while she was dying of cancer. She told Dr. Kerr on one of his last visits that she would be fine.

The process she had been resisting: that of letting go, was started by these visions.

It is difficult to change the health care system. The dying process is appreciated as a rich and unique human experience and Dr. Kerr still hopes to help patients and their loved ones regain the dying process from a clinical approach.

Daily deep knowledge. You can sign up for The Conversation's newsletter.

Pre-death dreams and visions help fill the void that may be created by doubt and fear. They help the dying reunion with their loved ones, those who secured them affirmed them and brought them peace. They restore dignity and heal wounds. Knowing about this reality helps the grieving.

Hospitals and nursing homes are still closed to visitors because of the coronaviruses, so it may be helpful to know that the dying rarely speak of being alone. They talk of being loved and put back together.

There is no substitute for being able to hold our loved ones in their last moments, but there may be solace in knowing that they were being held.

The Conversation is a news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. Carine Mardorossian is a professor at the University at Buffalo.

Read more.