The waves are moving three times faster than scientists thought they could.

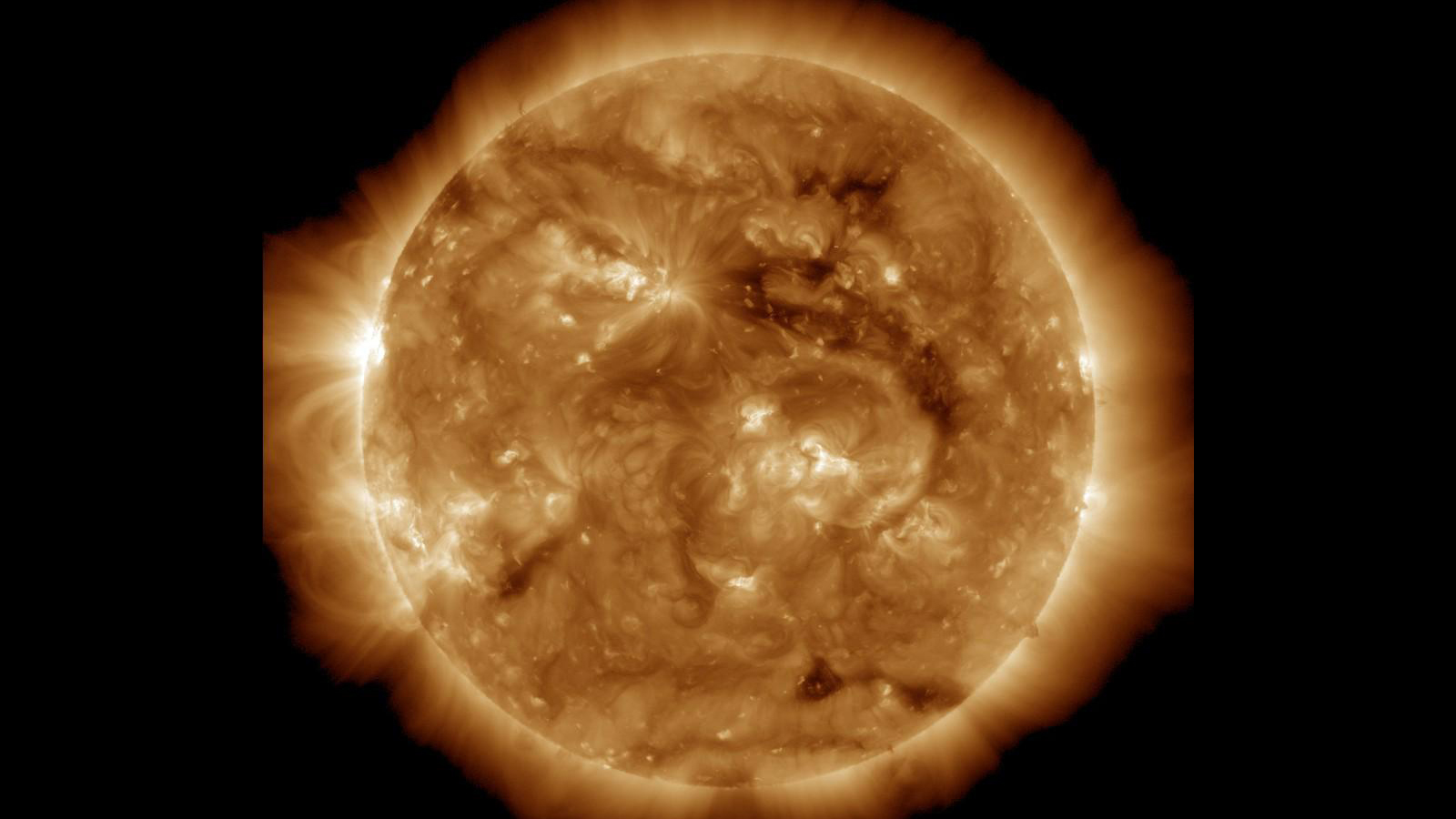

The HFR waves were seen rippling backward through the sun's plasma in the opposite direction of its rotation. A study published in the journal Nature Astronomy describes a previously unknown type of wave.

Scientists can't see into the sun's fiery depths, so they measure the acoustic waves that move across its surface and bounce back toward its core to infer what's going on inside. The unprecedented speed of the HFR waves, spotted in 25 years of data from space and ground-based telescopes, suggests that scientists might be missing something big.

Humanity has touched the sun, in a landmark achievement for space exploration.

The existence of HFR modes is a mystery and may be related to exciting physics, according to co-author Shravan Hanasoge.

Scientists thought that the acoustic solar waves form near the sun's surface because of the Coriolis effect, in which points on a rotating sphere's equator seem to move faster than points on its poles.

Scientists think one of three possible processes could accelerate the waves into HFR waves: either the sun's magnetic field or its gravity could be boosting the Coriolis waves, or superhot convection currents moving under and across its surface could be dragging them to unprecedented. None of these processes fit the data.

Chris Hanson, a solar physicist at New York University Abu Dhabi's Center for Space Science, said the finding would have answered some questions about the sun.

The new waves don't seem to be a result of these processes, and that's exciting because it leads to a whole new set of questions.

The researchers might be able to better understand the sun's interior, as well as get a better sense of how the sun affects Earth and other planets in the solar system by filling in the gaps in their knowledge. It could give insight into a wave called a Rossby wave, which has been seen traversing Earth's oceans four times faster than current models can explain.

It was originally published on Live Science.