Victoria Gill is a science correspondent.

Image source, ATOMIK

Image source, ATOMIKChernobyl moonshine started it all. Some scientists in the Chernobyl exclusion zone decided to use leftover grain to make alcohol.

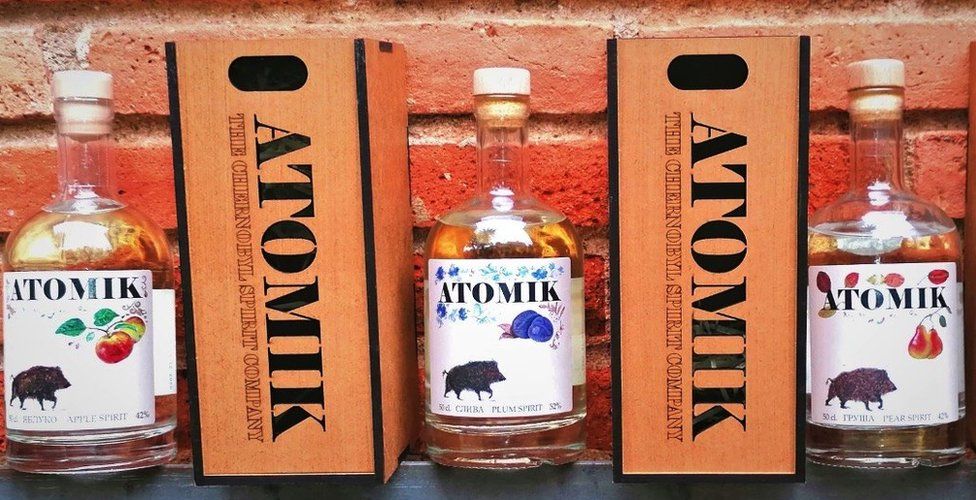

The social enterprise made and sold a spirit drink called Atomik.

The aim was to show that the slightly radioactive fruit grown in or near the exclusion zone surrounding Chernobyl could be distilled into a spirit that was not more radioactive than any other. Communities that live in deprived areas were the beneficiaries of the profits.

As Russian troops occupy the land where that fruit is grown and harvested, this unusual company is making a defiant marketing move by releasing two more premium drinks and donating profits to help Ukraine's refugees.

The future of an enterprise that makes a niche spirit is an example of how progress has been disrupted by war.

After studying the exclusion zone for 30 years, the scientists who set up the Atomik project allowed people to sell their own produce. It was a small but significant milestone in the recovery of a patch of Ukraine that was largely abandoned after the nuclear catastrophe in 1986.

The whole region where we harvest our fruit for production is occupied by Russian forces, according to a member of the Atomik team.

Military machinery kicking up radioactive dust in the usually carefully controlled zone caused a spike in radiation levels.

The information we are getting from the region is bad.

Russian forces have been accused of taking and destroying a research laboratory in the center of the exclusion zone.

One of the founding members of Atomik is Prof Jim Smith. He says that decades of progress is being destroyed because of the exclusion zone.

Image source, ATOMIK

Image source, ATOMIKThe communities that have been suffering for 35 years are now suffering more, he said.

The future of the Atomik project and the people who live and grow fruit in their orchards near the exclusion zone is uncertain.

If the war is over by the next harvest season, Kyrylo, who is still in his home in Kyiv with his wife and children, hopes to keep going. He wants to go back to his pre-war life and pick up the project that he left off.

The Chernobyl accident will no longer be the worst thing that happened there, so people there will need money and help.

Follow Victoria on social media.