We could watch whales and sharks adapt to climate change by measuring how they evolve and how their biology changes as temperatures and carbon dioxide levels rise. It could tell us a lot about the resilience of the oceans. It would take hundreds of years to understand our warming world today.

Consider the life of the copepod Acartia tonsa, a tiny and humble sea creature near the bottom of the food web. It creates a new generation in twenty days. The copepods pass in a year.

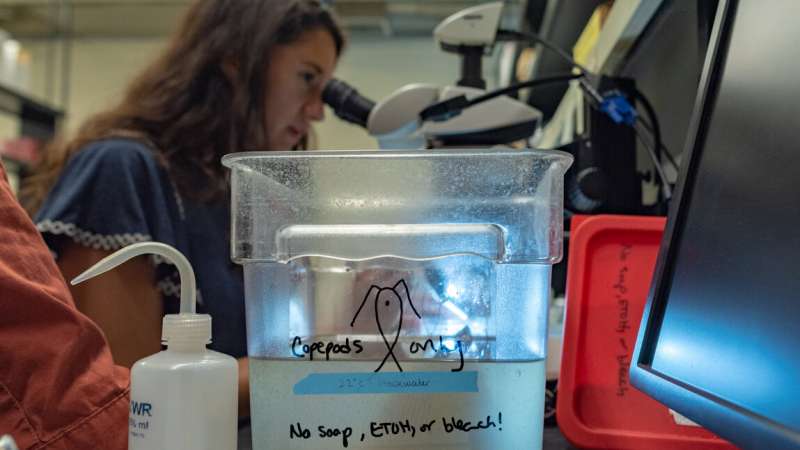

In a first-of-its kind laboratory experiment, a team of six scientists, led by University of Vermont biologists, exposed thousands of copepods to high temperatures and high carbon dioxide levels. As many generations passed, I watched. They took some of the copepods and brought them back to the baseline conditions that the first generation started in. As three more generations passed, they kept watching.

Pespeni says that the results show that there is hope, but also complexity in how life responds to climate change.

The price of change.

The team observed that the copepods did not die in the climate change conditions. They persisted and thrived. The scientists from UVM, University of Connecticut, and University of Colorado recorded many changes in the copepods genes related to how they manage heat stress. This shows that these creatures have the ability in their genetic make-up, using the variation that exist in natural populations, to adapt over twenty generations, evolving to maintain their fitness in a changed environment. The observations of the team support the idea that copepods, a globally distributed group of crustaceans eaten by many commercially important fish species, could be resilient to the unprecedented rapid warming and acidification now being unleashed in the oceans by human fossil-fuel use.

Pespeni says that the team observed what happened to the copepods that were returned to the baseline conditions. The hidden cost of the earlier twenty generations of adaptation was revealed by these creatures. The flexibility that helped the copepods to evolve over twenty generations was eroded when they tried to return to what had previously been benign conditions. The copepods were less healthy and produced smaller populations when brought home. After three generations, they were able to re-evolve back to their ancestral conditions, but they had lost the ability to tolerate limited food supply and showed reduced resilience to other new forms of stress.

If copepods or other creatures have to go down this adaptive path and spend some of their genetic variation to deal with climate change, will they be able to tolerate some new environmental stressor? A new study supported by the National Science Foundation supports the view that ceppods are resilient to rapid climate change.

"But we need to be careful of overly simple models about how well species will do and which ones will persist into the future, that look at just one variable," said Reid Brennan who completed this study. There may be unforeseen costs to quickly evolving in a suddenly-hot world according to a new study by the scientists.

More information: Reid S. Brennan et al, Loss of transcriptional plasticity but sustained adaptive capacity after adaptation to global change conditions in a marine copepod, Nature Communications (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-022-28742-6 Journal information: Nature Communications Citation: Ocean life may adapt to climate change, but with hidden costs (2022, March 21) retrieved 21 March 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2022-03-ocean-life-climate-hidden.html This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.