The biggest year-on-year change for 40 years is the change in the Formula 1 cars.

Aerodynamicists in the F1 teams have been working on their designs on and off since the beginning of the year, and this weekend represents a time of extreme anxiousness and high excitement as we find out for the first time how well we have interpreted the new rules.

The cars may look the same as those that ended the season. The rule book has been thrown out and the regulations started from scratch.

The shape of the car has changed. There is a bigger visual difference between the cars from different teams.

I work as a senior aerodynamicist in an F1 team, and this article is intended to guide you through what has changed and why, plus the key areas that will decide who is quick and who is not.

The rules have been in the works for five years and are the first to be based on research from within F1.

The last generation of cars made it difficult to overtake because they couldn't follow each other closely.

The main issue in car design was the way the aerodynamics worked.

The regulators believe that the new rules will lead to better racing because they want us to be in a direction which they deem aesthetically pleasing.

A wake is created when an F1 car drives around the track.

This is a bit like the water left behind a boat as it travels along, but as it is in the air you cannot see it.

The air in the wake is very turbulent. An F1 car needs clean air to work at their optimum and create the amount of down force that allows them to perform so well.

When one car got close behind another, the wake from the lead car reduced the down force of the following car, so it couldn't maintain its speed through the corners. Close racing and overtaking were very difficult because of this.

Something called outwash was the main reason for this. To make their cars work as well as possible, designers tried to push the wake created by the front wheels outward so that it didn't go over their own car and lose performance.

It came back just behind their car and washed over any cars that were close by.

The new regulations are supposed to stop us from washing the air. The new rules try to encourage more up washing.

They are trying to throw the wake up in the air so that it goes over the top of the car.

The team at F1 has done studies that show a reduction in wake that the following car experiences.

The figures look promising. The car lost 42% of its downforce when it was behind another car. A 2022 car should lose 15%. It should lose 8% at two car lengths, compared with 24% for a 2019.

This is the biggest rules change I have ever worked on, and many believe it to be the biggest in F1's history.

To find a change like this, you have to go back 40 years, to the winter of 1982. The changes that have been made are a reversal of what happened in the past.

Rule makers banned an aerodynamic design approach because they feared the cars were getting too fast.

The ground effect uses shaped tunnels to accelerate the air under the car. It is able to squeeze through the gap between the track and the car. This creates a low pressure area which sucks the car towards the track.

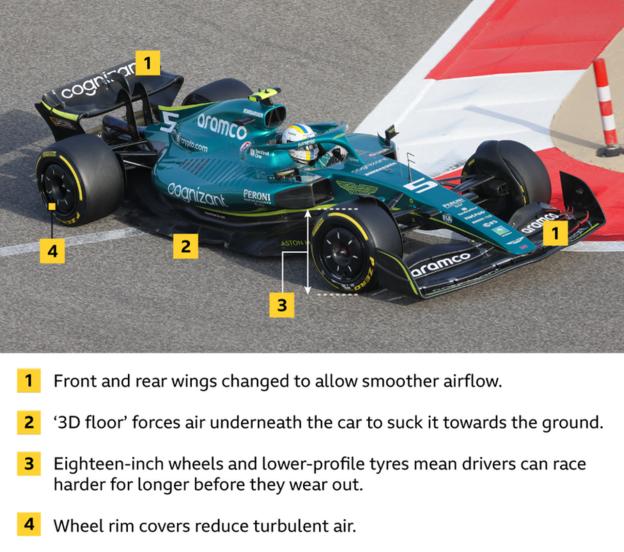

Flat undersides between the front and rear wheels have been a feature of F1 cars since 1983. The rule makers believe it will be effective in allowing cars to keep hold of a larger portion of their downforce when behind another car.

As a result of a wholesale change of philosophy, the underbodies are shaped again, and the front wing is less important in generating the airflow patterns that define the performance of the car.

The most obvious differences between the two cars are:

One thing is theory. Reality may be different. We don't know how well the new cars perform in relation to the theory until they compete together, and it will take a few races before a proper picture can be seen.

The previous generation of tyres were a major cause of the difficulty in overtaking, so it's not clear how well the new ones have been created.

One concern I have is that the extra upwash the cars generate behind them could cause the front wing of the following car to stop working.

Losing front downforce like that would make it more difficult for drivers to turn the cars into corners, and could affect some of the progress these regulations might make.

The beam wings have Diffusers.

This will be an area where development is focused and a lot of performance can be found because of the increased downforce of the cars.

If you can exploit the venturi effect under your car, that is a lot of down force.

The floors on these cars are very large. The venturi effect can be achieved by drawing all the air at the back of the car.

Teams were allowed to use vanes in the diffuser to turn the air in directions that aided performance last year. These are not allowed anymore. The aerodynamic element at the bottom of the rear wing has been replaced by a bigger beam wing.

The little flaps allowed last year can now be used with two substantial beam wing elements.

The changes will reduce our ability to outwash the air coming out from under the car, but will support upwards expansion, because the diffuser is pulling air under the floor.

There are edges on the floor.

To help seal off the tunnels from air outside, the edges of the floor drop slightly along the length of the car.

The venturi effect is dependent on this, as any air coming in from the side slows down the air that is upstream of it. To maximize downforce on a ground-effect car, we want to seal the edges of the floor.

One way to close the gap is to run the cars as low as possible. porpoising, which has been talked about since pre-season testing started, can present some problems.

Cars bounce up and down on straights. It's usually a result of high levels of downforce sucking a car down on to the road.

The cars get lower and lower until there is a point where the air cannot be worked harder. The whole cycle begins again when the car is brought back up by the sudden loss of downforce.

The floor can be sealed by blocking off the remaining distance between the edge of the floor and the track.

When air crosses a sharp edge, it forms tubes of air that spin around, just as we have at the sides of the floor.

There is a lot of detailing on the floor edges of the new F1 cars.

These are all about trying to form strong waves that are strong enough to seal the floor, and the sooner they start, the better.

Sidepods.

A lot of the decisions on the sidepods are driven by the clean air that strong vortices need to work properly.

How you shape the bodywork affects where you can feed clean air to and where you draw it from.

Some teams, such as Mercedes and McLaren, seem to be down washing their sidepods. Their bodywork sweeps down from the sidepod inlet towards their floor aggressively.

They are trying to get clean air from above to the floor early.

The super- slim design that Mercedes brought to the second test was extreme.

The winglet in front of the bodywork appears to be the key to their concept. The components all work together to set up a large scale rotation of the air, heading downwards at the centre of the car, then downwards towards the floor edge.

The Mercedes bodywork is sympathetic to the air flowing down towards the edge of the floor.

The narrow width keeps the bodywork away from the front wheel wake. This will help to prevent the wheel wake from attaching to the bodywork and then staying with it all the way down the car, ruining the flow of our carefully designed floor and rear corner.

If you pull the upper wheel wake in from above, it will head towards the rear corner of the car. You feed clean flow to the front but not at the expense of the rear.

Red Bull has gone for sidepods that are wider at the top. The floor edge will be fed with air that has gone under the sidepod. The clean air was sent towards the rear corner.

Some people are calling the concept of a scalloped cutout in the top of the sidepods a baby bath, and they have found a solution with Ferrari.

The interaction with the front wheel wake will be important in this design. The high pressure from the very flat sides will push the wheel wake out, away from the floor, as well as driving strong floor-edge vortices, before the air over the concave, upper surface is delivered to the rear of the car.

There are mini floor wings.

There is a lot of variation in the floor edges. The decisions they have already made on their sidepods are the reason why each team has ended up with will. They are all trying to achieve the same thing.

The floor-edge wing is an interesting difference in approach. The winglets seen on the floor edge of last year's cars were intended to be allowed under the rules, and that is the approach taken by some of the teams.

There is no need for these wings to be above the floor. Some teams have decided to put theirs under the floor. They can make strong, floor-sealing vortices from there.

The back of their floors are hiding some of the more smilng bumps.

I have seen the spy shots from the long lens cameras and they are definitely there.

Some of the problems we are trying to solve when designing an F1 car can be found here. No one decision in isolation makes a winning car.

There was a concern last year that the new rules would cause all the cars to look the same. That is far from what has happened.

I've been surprised by the amount of variation in the field.

In areas where there is some freedom, such as the bodywork, we looked at most of the concepts you can now see up and down the pit lane, did our research and came to our conclusion on the best direction to take.

I assumed that everyone else would come to the same conclusion. It's not clear who was right or who was wrong.

Once we go racing this weekend, we will be able to see which design philosophy produces the fastest car. We are in for a fascinating season, that is the only thing I am sure of right now.