School was canceled the next day. In response to the chaos of the previous night, the Brooklyn Center City Council hurried to pass a resolution banning aggressive police tactics such as rubber bullets, tear gas, andkettling. There was a curfew from 7 to 6 a.m. The council's resolution went into effect on the 12th, but police continued to use banned tactics. Approximately 20 businesses were broken into that night.

Customs and Border Protection Helicopters were summoned from the US Department of Homeland Security as part of the operation. The presence of circling aircraft would become a hallmark of the operation. During the peak of the protests, the helicopters flew from a difficult-to-access industrial area near the Mississippi River between Brooklyn Center and Minneapolis to avoid detection.

During the height of the protests, law enforcement took detailed photographs of members of the press who were covering the events and briefly detained them.

The class action lawsuit against the city over its treatment of journalists during the protests has been settled by the American Civil Liberties Union and two private law firms. The settlement requires the city to pay over $800,000 to injured journalists, and a federal judge ordered an injunction lasting six years that prohibits Minnesota policing agencies from attacking and arresting journalists.

The state's use of force against Minnesotans exercising their First Amendment rights in Brooklyn Center and militarization of our cities is what the 75 community organizations called for on April 15. The NAACP called out the use of militaristic tools of oppression to intimidate and halt peaceful protest.

The Minneapolis Legislative Delegation, a group of state legislators, sent a letter to Minnesota governor Tim Walz condemning OSN and asking for a rethink of tactics. The investigation is still going on.

The operation cost tens of millions of public dollars. According to an email sent to MIT Technology Review, the Minnesota State Patrol paid over $1 million and the Minnesota National Guard paid at least $25 million.

Most details of OSN's attempts to surveil the public remained secret despite the public costs.

According to Lieta Walker, a lawyer, MIT Technology Review obtained a watch list used by the agencies in the operation that included photos and personal information of journalists and other people. It was compiled by the Criminal Intelligence Division of the Hennepin County Sheriff's Office, one of the groups that participated in OSN.

The Minnesota State Patrol and Minneapolis Police Department both told MIT Technology Review in an email that they were not aware of the document.

OSN used a real-time data-sharing tool called Intrepid Response, which is sold on a subscription basis by AT&T. Credentialed members of the press who were covering the unrest in Brooklyn Center were temporarily detained and photographed, and those photos were uploaded into the Intrepid Response system.

The State Patrol denied many records requests from MIT Technology Review, but J.D. Duggan was able to get his personal file. The pages include photos of his face, body, and press badges, as well as time stamps and maps showing the location of his brief detention, which illuminates the extent of law enforcement's efforts to track individuals in real time.

Police agencies participating in OSN had access to a number of other technological tools, including a face recognition system made by a controversial firm, cell site simulators for cell-phone surveillance, license plate readers, and drones. A core part of OSN was social media intelligence gathering.

During the protests after Floyd's murder, a technology typically used to monitor battlefields in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere, was spotted flying over the city. The police already own the better aerial surveillance technology, which was shown in the two National Guard spy plane flights. In a report, the inspector general of the US Air Force said that the helicopter imagery provided by the Minnesota State Police was better than that provided by RC-26 spy planes. The police obtained a warrant to get information on people involved in the May 2020 protests.

OSN requires officers from nine agencies in Minnesota, 120 out-of-state supporting officers, and at least 3,000 National Guard soldiers. Several different intelligence groups collaborated throughout the operation to manage the surveillance tools. The structure of these intelligence teams, the personnel, and the extent of federal agencies involvement have not previously been reported.

The Strategic Information Center is located in the same area where federal agencies were flying in and out of. The SIC was a central planning site for the operation safety net and also afusion center for the Minneapolis police department. The facility has the latest technology and is plugged into the city's camera feeds and data-sharing systems. The SIC was used frequently by OSN leaders to coordinate field operations and intelligence work.

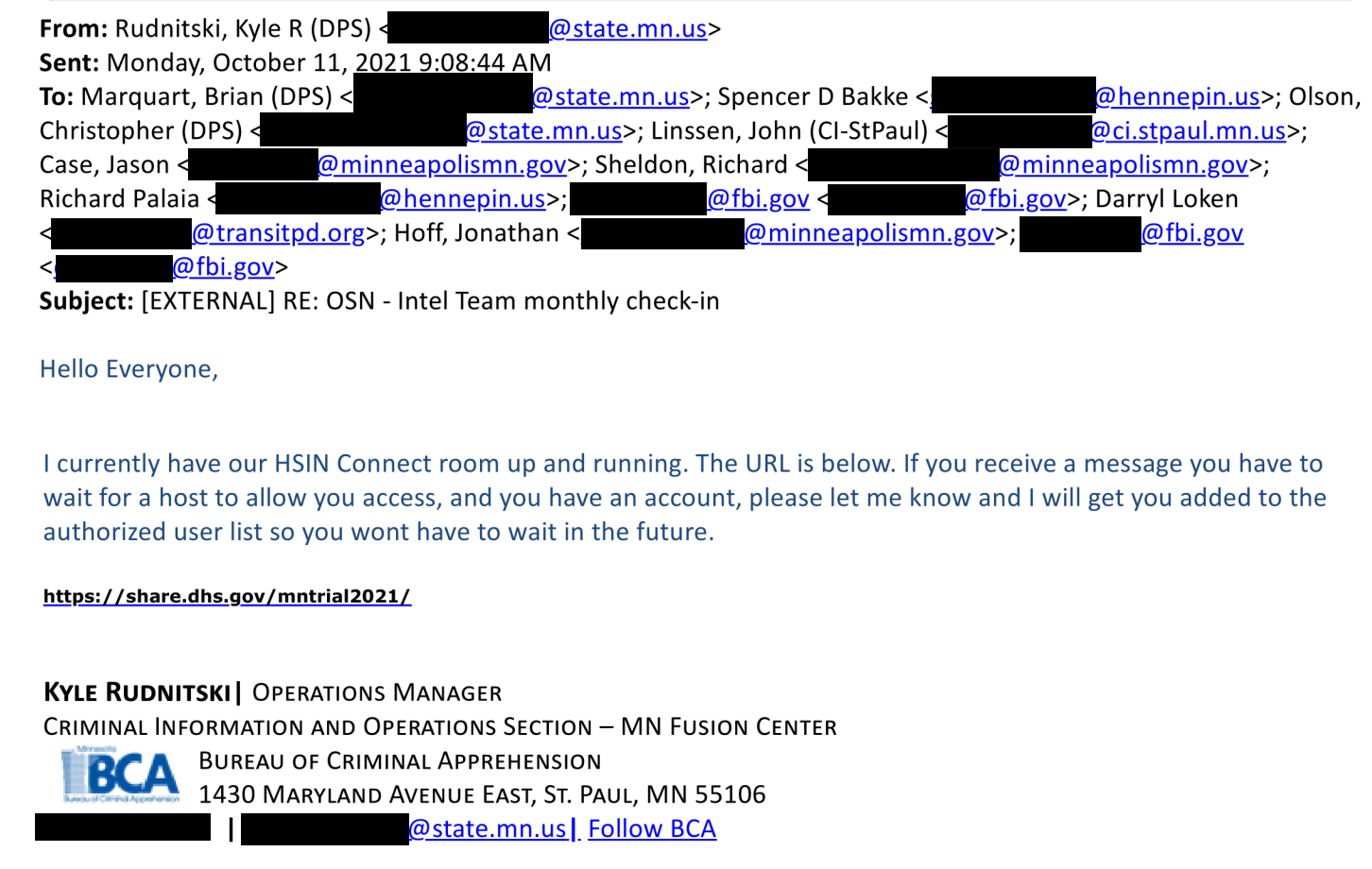

Emails obtained through public records requests shed light on anintel team within operation safety net It was made up of at least 12 people from various agencies. The intel team used the Homeland Security Information Network (HSIN), run by the US Department of Homeland Security, to share information and met regularly through at least October 2021. Bruce Gordon, director of communications at the Minnesota Department of Public Safety, told MIT Technology Review in an email that the state Bureau of Criminal Apprehension's (BCA) fusion center has access to facial recognition technology.

Four FBI agents are included in the executive team of operation, along with two intel agents, as a result of our investigation into the involvement of federal agencies at the highest level of the safety net. During the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, federal agents were deployed to several cities, including New York and Seattle. In Portland, Oregon, the FBI covertly filmed activists. On June 2, 2020, the deputy director of the FBI released a memo encouraging aggressive surveilling of the activists, calling the protest movement a national crisis.

Kyle Rudnitski acted as the administrator of HSIN for the intel team and the host for planning meetings, according to his email signature. Rudnitski was in charge of account permission for the team.

The primary data-sharing center for Minnesota is the BCA's fusion center. The facility is staffed by criminal intelligence analysts and others who run a constellation of intelligence-gathering tools and reporting networks.

Intelligence-sharing and analysis hubs are spread throughout the country and bring together intelligence from local, state, and federal sources. In the wake of the 9/11 terror attacks, these centers were set up to consolidate intelligence and quickly assess threats to national security. According to the Department of Homeland Security's website, these centers are intended to increase collaboration between agencies through data sharing. Multiple police agencies, federal law enforcement and National Guard personnel are sometimes called to work at the centers. The risk of abusive policing practices has been raised by the proliferation of these centers.

Instead of looking for terrorist threats, fusion centers were monitoring political and religious activity. A 2012 report from the Brennan Center describes a Muslim get-out campaign as "subversive". An investigation by the Senate found that such tactics were not uncommon. It concluded that fusion centers produce useless or inappropriate intelligence that endangers civil liberties.

Minneapolis police shot and killed a young Black man, who appeared to be sleeping on a couch, when they executed a no-knock warrant as part of a homicide investigation. Locke wasn't a suspect in the homicide, as initial police press releases claimed.

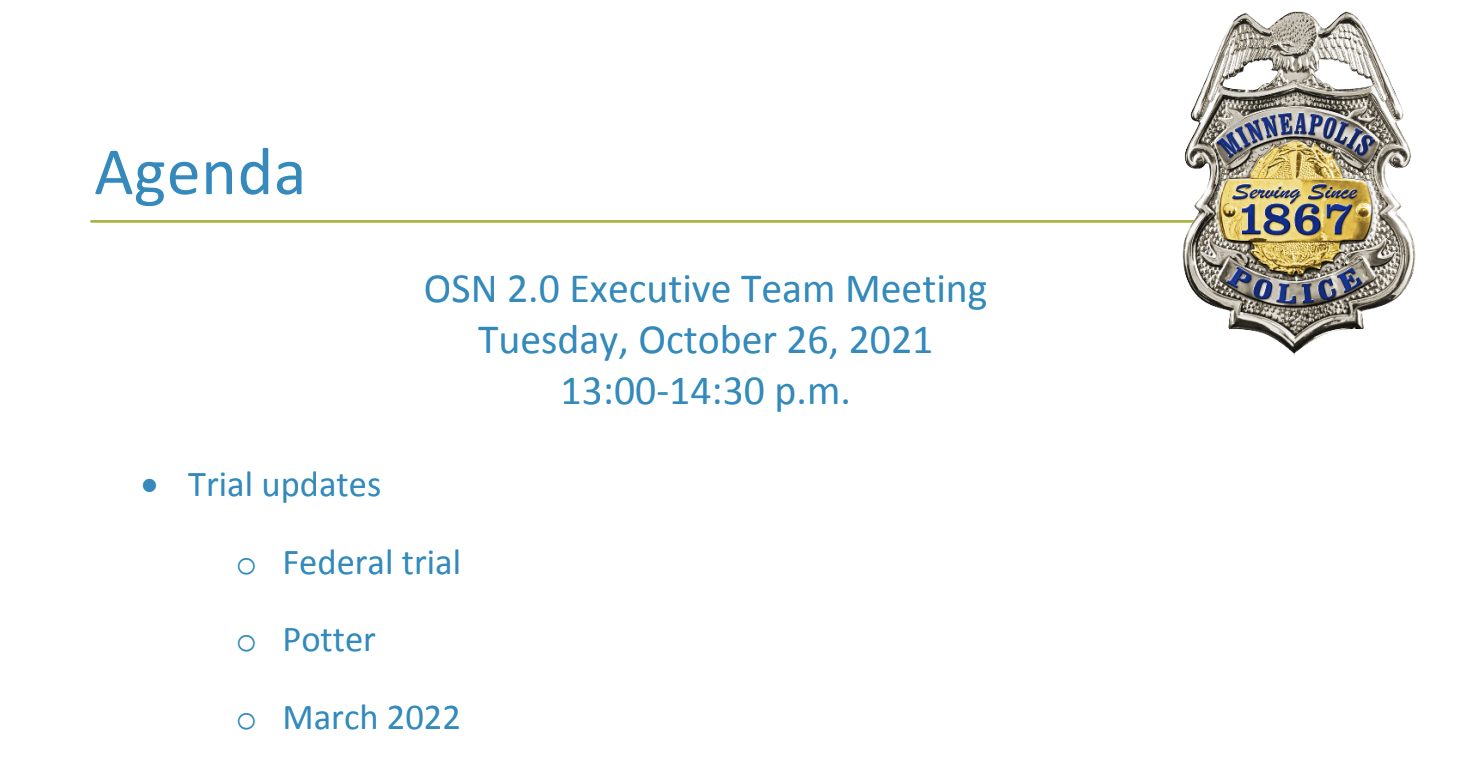

The final phase of the OSN operation would begin on April 22, 2021. According to documents obtained by MIT Technology Review, regular planning meetings, secured chat rooms, and the sharing and updating of operation documents remained in effect through at least October.

The emails contained information about a meeting on October 26, 2021, for the OSN 2.0 Executive Team, which included items related to the trial of Kim Potter.

Gordon told MIT Technology Review that there was never an OSN 2.0 and that any reference was an informal way of notifying state. This was not unique to the time when OSN existed.

The three other officers who were on the scene of George Floyd's murder were found guilty of federal crimes, though they still await a state trial.

A new era of protest policing has been created by the events in Minnesota. Protests that were intended to call attention to the injustice committed by police gave those police forces an opportunity to consolidate power, strengthen their inventories, and update their technology and training to achieve a far more powerful, connected, and surveilled apparatus. This investigative series will show how new titles and positions were created within the Minneapolis Police Department and the aviation section of the Minnesota State Patrol that use new technologies and methods.

Anonymity is important to free speech. Anonymity is a shield from tyranny, according to a landmark 1995 Supreme Court case.

But a wild proliferation of technologies and tools have recently made such anonymous free speech nearly impossible in the United States. This series will provide a rare glimpse behind the curtain during a transformative time for policing and public demonstration in the US.