A snowboarder is Bibian Mentel-Spee. She loved the camaraderie of the riders, the thrill of competing, and the feeling of being in the mountains.

She was a pioneer in the inclusion of her sport in the Winter Paralympics. She was an inspiration to millions as she overcame enormous health challenges. The first anniversary of her death will be before the Games of Beijing 2022.

She was not afraid to die, says her husband.

She was afraid to leave behind her son. She was not afraid of dying in the last five weeks.

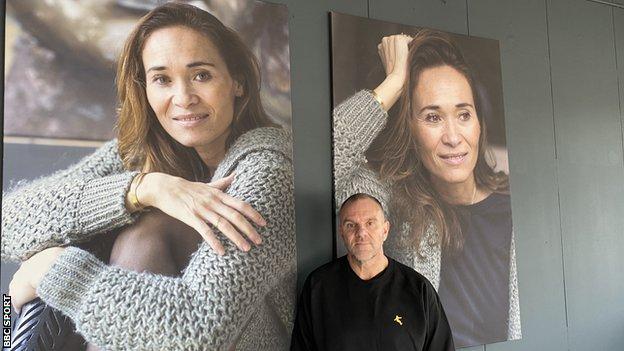

We are talking in the office of the charity that Mentel-Spee founded and that is run today.

There is a portrait on the wall. As he talks, his gaze flickers up to the image of his late wife and he pauses frequently, his eyes still on her.

He says thatbian was always giving love and that she got a lot of love back from the world.

She chose to live. She decided to become the best version of herself. She was a master at living life to the max.

Mentel-Spee died on March 29, 2021. She will be remembered for many years to come because of her achievements in winter sports.

During her campaign to qualify for the Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City, Mentel-Spee began her journey to becoming a Paralympian legend.

When she was diagnosed with bone cancer in her lower right leg at the age of 29, she was a successful snowboarder who was going to the Olympics.

Radical action was needed despite treatment.

She had to choose between her life and her lower leg.

It would be the beginning of almost two decades of illness and medical interventions. It was the beginning of a sporting life that would inspire millions.

Even after the operation, Mentel-Spee was back to her best, winning a seventh national title, despite the doubts of her doctors.

As a newly disabled athlete, Mentel-Spee was spurred to push the boundaries of her sport.

He says that she got that feeling that he had cancer, lost his leg and was back on his snowboard.

She knew she had to do something to show the world that this is possible. She decided to start a campaign after that.

The campaign was to get snowboarders into the games. It took a long time.

There were other riders in similar situations to Mentel-Spee, but there was little infrastructure, no common rules, and no global competition.

With a group of other Para-snowboarders from around the world, she set to work.

They organised a World Cup circuit, arranged sponsorship, Lobbyed officials and tried to keep the sport in the public eye. She wanted to prove that her sport was at the top table.

She had to make a choice because of her desire to grow the sport.

Mentel-Spee continued to compete in overall competition against able-bodied competitors after the campaign for Para-Snowboarding. She had to commit now.

If I want the Paralympics, I need to make a decision. Do I race with the able bodied or do I only race with the physical disabilities?

She quit able-bodied racing and moved to racing with disabled snowboarders.

The result was worth it for Mentel-Spee and her colleagues.

After eight years of campaigning, she got a phone call saying that snowboarding would be on the schedule at the Paralympics.

Even as she continued her career and worked on her campaign, she was 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217 800-273-3217

Every time she had to have surgery she knew it was going to be bad, but maybe it would go away for a year or two. It was gone for almost five years.

She was the favourite to win the gold medal in the first Paralympics snowboarding competition when it happened.

The burden of expectation and the effort she had put into the campaign to get to the Games left their mark.

I have never seen an athlete that nervous. This magic around these races is different.

Mentel-Spee went on to win gold, ahead of France's Cecile Hernandez-Cervellon and the USA's Purdy.

The medal was more than just a mark of success.

It was a big achievement as the first Paralympic snowboard gold medal, that you can win everything, even the fight against cancer. We still believed she could grow old.

At the closing ceremony of the Olympics, Mentel-Spee received a special award for her achievement.

She was if anything, Edwin says, more proud of that than her gold medal. And it is clear that her work with her charity, the Mentelity Foundation, was at least as important to her as sporting success.

She set it up in 2012 in the midst of her own competitive career and continued struggles with illness, to help share the joy and freedom of boarding and snow sports with young disabled people in her native Netherlands.

She continued to work until just days before she died. Even in the last weeks, when she couldn't use her wheelchair, she talked of packed evenings full of Zoom calls.

The work that the Foundation continues today is helping introduce young people to board and snow sports, funding and providing artificial limbs, and putting on events and competitions.

We promised Bibian to continue her legacy, her work for the Foundation, and that is to make life for children with a disability as good as for their able-bodied friends, to give them the same opportunities.

In the spirit of Bibian, this is always something to do with a board, so we have wake boarding, snowboarding, surfing, skateboarding, stand-up paddle boarding.

There are lessons, trips to the mountains, coaching, support and fun.

The idea is that disabled young people can play and compete in the same way as their able-bodied counterparts, just as Mentel-Spee had done before.

She helped a lot of people with the Foundation, but she gained a lot from it.

She got so much love back because she gave so much. Helping other people was what drove her through her life.

There were thousands of people next to the road when she died.

If you want to see what Bibian Mentel-Spee was like, you can watch the video. There is a lot of material available. She was a public speaker.

She was candid about both her health problems and her successes.

There's a TEDx talk she gave in 2018 in Amsterdam, six months or so after winning double gold at the Pyeongchang Paralympic Games.

She shows an X-ray of her neck and metal construction which has replaced a part of her spine.

She says it is titanium and it was a result of another cancer.

She went to South Korea for her second Winter Paralympics just weeks after having 16 hours of surgery to remove a tumours in her neck.

Doctors said she probably only had a few more months to live. She was getting ready to go again.

There were questions about whether it was the right thing for her to be in the Olympics given her health problems.

According to her husband, Mentel-Spee's answer was clear.

She said that this is the thing that keeps her alive because she is in better health than if she were at home and waiting for her life to end.

She went in the spirit of the Games and said that participating is more important than winning. This was her state of mind.

The standards in her sport have developed significantly since the Olympics of 2014, as well as her own health issues. She was still a contender even at the age of 45.

She had to work harder on the technical aspects of racing because of her neck surgery.

She won the snowboard cross and banked slalom for the second year in a row, and she could still be a winner.

She had 128 victories over her racing career and two more gold medals to add to that.

After the Olympics, Mentel-Spee stopped competing and focused her efforts on the Mentelity Foundation.

She had to use a wheelchair after needing more operations and treatments. Her health deteriorated in the last months of her life.

The opening of a sports facility named after her was her last public engagement. She was thrilled to be there.

She said that she got a lot of positive energy from it.

When he sits down to watch the snowboarding events in Beijing, he isn't sure how he will feel.

He will be watching as Dutch snowboarders such as Lisa Bunschoten and Chris Vos go for gold under the guidance of Mentel-Spee.

He says he will be laughing and having good memories. I don't know.

He knows how she would react.

The funny thing is that Bibian never cried. She would cry if someone won a gold medal.

She wasn't crying but other stuff.