Since being identified in people, the disease has spread to a wide range of animals. There are concerns that the species jumps could lead to novel changes.

The researchers from the University of Pennsylvania's School of Veterinary Medicine and Perelman School of Medicine found that for at least one example of apparent interspecies transmission, this crossing the species boundary did not cause the virus to gain a significant number of mutations.

A domestic house cat that was treated at Penn Vet's Ryan Hospital was found to have a variant of the disease after its owner came in contact with it. The full genome sequence of the virus was very similar to the viral sequence in the Philadelphia region at the time.

Elizabeth Lennon, senior author on the work, a vet, and assistant professor at Penn, says that the work has a wide host range.

This is the first instance of the delta variant occurring in a domestic cat in the United States. Testing the cat's fecal matter was the only way to identify the infection. A positive test did not result from a nasal sample.

The importance of sampling at multiple body sites was highlighted by this.

Lennon and colleagues have been sampling dogs and cats for the disease. A pet cat was brought to Ryan Hospital in September with gastrointestinal symptoms. It had been exposed to an owner who had been isolating from the cat for 11 days before it was hospitalized.

The team obtained a whole genome sequence of the cat's virus from Frederic Bushman's laboratory at the Penn Center for Research on Coronaviruses and Other Emerging Pathogens.

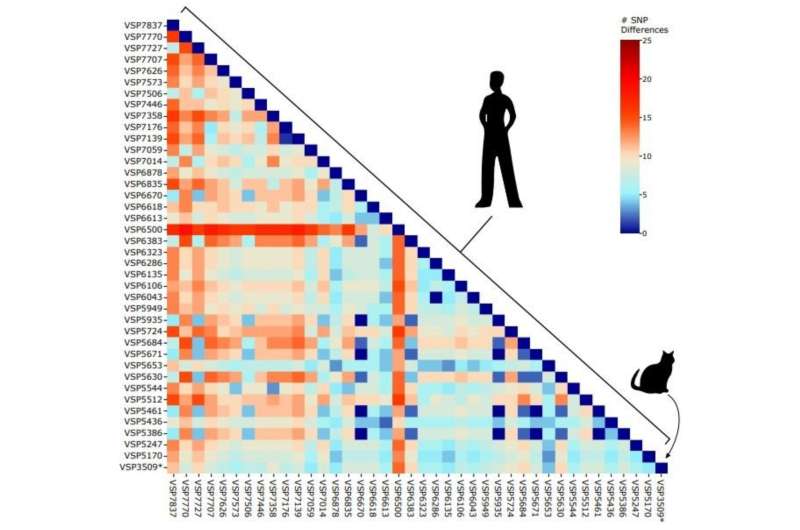

The AY.3 lineage was revealed by the delta variant. The researchers didn't have a sample from the owner. The sequence of the cat's virus was similar to the one circulating in the Delaware Valley region at the time.

Lennon says that there wasn't anything dramatically different about the cat's sample.

Not all of the different versions of SARS-CoV-2 have been able to cause the same amount of damage. The original strain of the Wuhan strain was not able to cause harm to mice. The early days of the Pandemic were when scientists began to see infections in cats and dogs.

Lennon says that as different versions of the disease emerge, they seem to be retaining the ability to cause a wide range of diseases.

Lennon and colleagues, including Bushman and Susan Weiss of Penn's medical school, hope to continue studying other examples to see how the virus evolved. The Institute for Infectious and Zoonotic Disease at Penn Vet will look at human- animal interactions when it comes to pathogen transmission.

Lennon says that they know that the SARS-CoV-2 is changing as it passes between becoming more and more transmissible. Host-adapting to people is what it is. Does the virus adapt to other animal species when they get it? Do the viruses that may adapt to a different species still affect humans?

More information: Olivia C. Lenz et al, SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant (AY.3) in the Feces of a Domestic Cat, Viruses (2022). DOI: 10.3390/v14020421 Citation: Genome sequence of COVID in a cat nearly identical to viral sequences found in people (2022, March 1) retrieved 1 March 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2022-03-genome-sequence-covid-cat-identical.html This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.