An underwater volcano in the South Pacific erupted last month and shattered two records at the same time: The volcanic plume reached greater heights than any eruption ever captured in the satellite record, and the eruption generated an unparalleled number of lightning strikes over the course of three days.

The combination of volcanic heat and the amount of superheated water from the ocean made this eruption unprecedented. Kristopher Bedka, an atmospheric scientist at NASA's Langley Research Center who specializes in studying extreme storms, said in a statement that it was like hyper-fuel for a mega-thunderstorm.

The volcano is located north of the capital of Nuku'aloFA and is part of the so-called Tonga-Kermadec volcanic arcs.

Elves, blue jets, and Earth's weird lightning are related.

The eruption began on January 13th and caused a major lightning event. On January 15th, rising magma from the volcano caused a huge blast above the volcano. When water is quickly heated into steam by magma, it expands quickly, and bubbles of volcanic gas help to drive these dramatic blasts up and out of the water, Nature reported.

The Jan. 15 eruption was an exception to the rule that underwater volcanic eruptions do not release large amounts of gas and particles into the air.

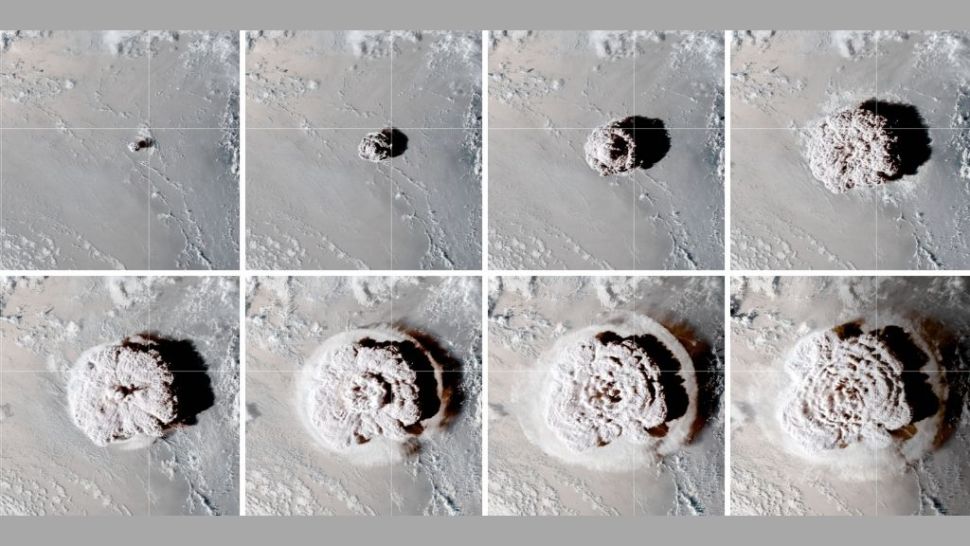

Two weather satellites captured the eruption from above.

From the two angles of the satellites, we were able to recreate a three-dimensional picture of the clouds.

There are 10 incredible volcanoes in our solar system.

According to the NASA statement, they determined that the mesosphere was pierced by the plume at its highest point. A secondary blast from the volcano sent ash, gas and steam more than 30 miles into the air.

In 1991, Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines unleashed a volcanic eruption that lasted 22 miles above the volcano, and it was the largest known volcanic eruption in the satellite record.

When the highest portions of the plumes reached the mesosphere, they transitioned into a gaseous state. The volcano's gas and ash spread to cover an area of 60,000 square miles.

Chris Vagasky, a meteorologist at the environmental technology company, said that the eruption appears to have created waves in the atmosphere. Vagasky and his colleagues are still studying the lightning activity generated by the eruption, and they are interested in how these atmospheric waves influenced the pattern of lightning strikes.

The data from the lightning detection network is being used by the team. The data shows that about 400,000 lightning strikes took place within six hours after the big blast.

The largest volcanic lightning event in the history of Vaisala happened in Indonesia in the year of Anak Krakatau, generating about 340,000 strikes over a week. More than 1,300 strikes landed on the main island of Tongatapu, after the team determined that about half of the lightning struck the surface of the land or ocean.

There were two flavors of lightning. Dry charging is when ash, rocks and lava particles collide in the air and swap negatively charged electrons. The second type of lightning was caused by ice charging, which occurs when the volcanic plume reaches heights where water can freeze and form ice particles that slam into each other.

The processes cause the electrons to build up on the undersides of the clouds and then the negatively charged particles jump to higher, positively charged regions of the clouds or to the sea below.

The percentage of lightning that was classified as cloud-to-ground was higher than you would normally see in a typical thunderstorm and that creates some interesting research questions.

It was originally published on Live Science.