The government announced additional vaccine booster jabs for the over-75s last week and said a further shot is likely to be needed in the autumn. Imagine if the next Covid vaccine was the last you needed. Researchers feel it could be possible to make a universal vaccine against the sars-coV-2 virus, which would work well against all existing versions.

Some are thinking bigger. In January, Joe Biden's chief medical adviser, Anthony Fauci, and two other experts called for more research into a vaccine against coronaviruses.

Is that a real thing? Not necessarily. It was thought that we would have a vaccine against Covid-19 in less than a year. The experience has proved that the research community can pull together and do remarkable things.

The current vaccines were developed against the original version. Even against Delta, they still work well against the new variant in preventing severe disease. The Omicron variant has caused alarm because of its ability to transmit quickly and to cause disease. Omicron can suppress the immune defences of individuals who have not been exposed to it.

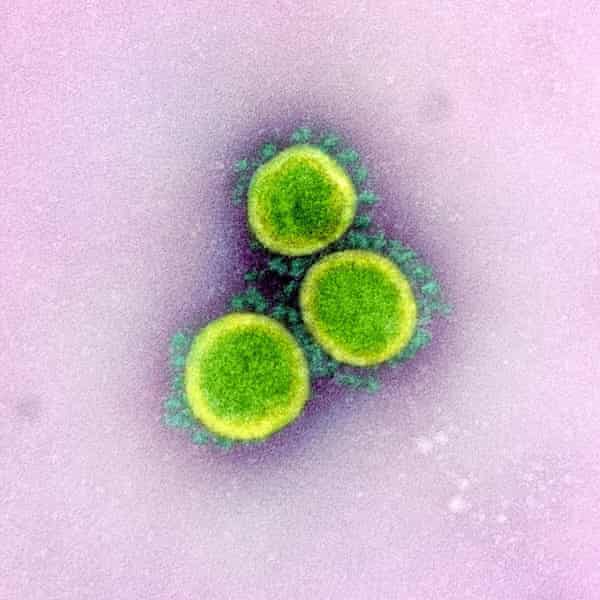

When the virus replicates, theVariants acquire changes to the chemical structure of the viral proteins that give them some competitive advantage. Many of these changes happen on the spike protein, which sticks out of the virus shell and attacks the cells with a point of attachment. Omicron has an alarming number of such mutations, showing how much capacity Sars-CoV-2 has to spring surprises.

The vaccines can be adapted to the variant. The vaccines made by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna contain templates for our cells to make harmless fragments of the spike protein. This is the vaccine that causes the immune system to fight the virus. Our immune system is ready to destroy the actual virus if it enters our bodies. Other vaccines use other methods to get the same immune response. In principle, we can change the RNA molecule to one that contains part of the new variant if it has a slightly different structure.

One option is to give the immune system many ways to spot, and suppress, the invader, in the hope that one will work

The vaccines could be tailored to any variant of the disease if it becomes endemic in the population, and if it becomes an epidemic with the potential to produce an outbreak. Each season's flu vaccine is based on a best guess of what the season's strains are likely to be.

That's all well, except that Omicron has shown how quickly a new variant of the coronaviruses can spread. Pfizer and Moderna are working on a vaccine. It may be too late if this can be made and tested within a few months. A vaccine that can protect against all of the coronaviruses is needed.

We don't have a pan-variant vaccine for endemic viruses. There are promising signs that a universal vaccine could be possible, which would make flu epidemics less lethal. Similar lines would be followed by the design principle for a universal Covid vaccine.

One option is to prime the immune system to recognize a lot of bits of a different version of the same virus. We would give the immune system many different ways to spot and suppress the invader in the hope that one will work. An example of this would be to make a vaccine that contains many different genes, each with a different function. A single particle could hold several different fragments.

If you look for parts of the virus that seem to be conserved, you can find parts that don't change much at all. How can you know what those will be, even if they haven't emerged yet? If you can find things that are in common between the two, you can see if there are highly conserved regions among a whole family of related coronaviruses.

At the moment, researchers are trying to hit just a subset of the coronaviruses universe, which is usually to cause an immune response against a part of the spike protein. The host cells have a spike protein that can be found in theRBD. The chemical structure of the variant doesn't change much, it should work against any virus in this family, and it has small changes in itsRBD.

Modjarrad's team began Phase I clinical trials in April of 2021. The ferritin is studded with many copies of the sars-coV-2RBD, a natural iron atom store.

It has been known for a long time that a stronger immune response can be elicited by many copies of the same vaccine particle. The institute doesn't want to give out any information until the clinical trial data is published. In December, the team published results showing that their ferritin vaccine confers good protection in macaques not only against the ancestral form of sars-coV-2 but also against the Alpha,Beta, and Delta variant and the original sars virus.

Barton Haynes of the Duke University School of Medicine in North Carolina is using ferritin-based nanoparticles. He and his coworkers reported a vaccine that protected macaques against some bat coronaviruses. They showed that it generated a good immune response against the Delta and Omicron variant.

Haynes says they hope to start human trials at the end of the century. If they work out, he thinks it will take a year or two before the vaccine is ready to use, depending on whether it is different enough from the ones we already have to conduct another large-scale Phase III clinical trial.

The universal coronaviruses vaccines that Fauci and colleagues have called for might have an even wider scope if these efforts are successful. Haynes says that finding the crucialRBDs for other families and adding those on to the particles would be necessary. The beauty of the approach is that it can incorporate a variety of fragments into a vaccine.

The first axiom of infectious disease is, never underestimate your pathogen. One wouldn’t bet against this virus

Finding the right fragments for the coronaviruses could mean combing through thousands of them, as well as the four coronaviruses already endemic in human populations and which cause mild cold-like respiratory symptoms. It would be difficult. The investment would be cheap compared to the economic and social harm it would cause. It might be possible for a single jab to protect against all coronaviruses for five to 10 years.

No one knows what the Covid-19 virus will do in the future. One wouldn't bet against it.

Even viruses have limits. The sotrovimab still works against it despite the extensive set of mutations.

We're building up an arsenal of antivirals and other treatments, and the current vaccines still do well at preventing deaths. A vaccine that blocks transmission is more important now than ever. He says that even when death rates are reduced, the things that make modern culture be interfered with. It would be difficult to assess the effectiveness of second- generation vaccines until they are rolled out.

Virgin says that it is tempting to think that we need to solve the Pandemic before preparing for the next one. It's easier for governments to spend on solving an existing problem than on one that hasn't happened yet, he says.

Neil King of the University of Washington in Seattle is working on a vaccine that will prevent the next epidemic.