A new method of dating asteroids and planetary bodies could help scientists reconstruct how and when planets were born.

The Chelyabinsk meteorite, which fell to Earth and hit the headlines in 2013), was combined with other ancient impact events to get more accurate constraints on the timing.

Their study, published in Communications Earth and Environment, looked at how minerals within the meteorite were damaged by different impacts over time, meaning they could identify the biggest and oldest events that may have been involved in planetary formation.

Craig Walton, who led the research and is based in the area, said that the work shows that we need to draw on multiple lines of evidence to be more certain about impact histories.

Early in the history of the Solar System, planets like the Earth were formed from massive collision between asteroids and larger bodies.

Evidence of these impacts is so old that it has been lost on the planets, according to the co-author.

meteorites are cold and old, but asteroids are cold and young, making them faithful timekeepers of collision.

The new research, which was a collaboration with researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Open University, recorded how the Chelyabinsk meteorite was shattered to varying degrees in order to piece together a collision history.

They wanted to corroborate the time elapsed for one of the elements to decay to another in the meteorite.

The shock events experienced by the meteorites on their parent bodies can be dated by using the phosphates in primitive meteorites.

There are two impact ages of this meteorite, one 4.5 billion years old and the other 50 million years old.

These ages are not clear-cut. A once clear picture can be obscured by successive collisions, leading to uncertainty among the scientific community over the age and even the number of impacts recorded.

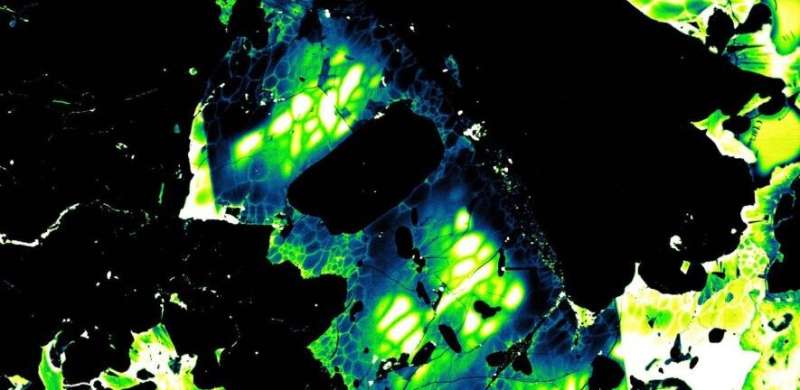

The new study shows that the Chelyabinsk meteorite had new lead ages that were linked to evidence for heating inside their crystal structures. The minerals have tiny clues that build up with each impact, so they can be distinguished and dated.

Their findings show that the minerals in the oldest collision were either shattered into many smaller crystals at high temperatures or severely damaged at high pressures.

Some mineral grains in the meteorite that were fractured by a lesser impact, at lower pressures and temperatures, and which have a much more recent age of less than 50 million years, were described by the team. The Chelyabinsk meteorite may have been knocked off its host asteroid by this impact.

The question for us was whether these dates could be trusted, could we tie these impacts to evidence of superheating from an impact?

The date of the 4.5-billion-year-old impact is important to scientists because they think the Earth-Moon system came to be as a result of two planetary bodies colliding.

The Chelyabinsk meteorite is part of a group of stony meteorites, all of which contain highly shattered and remelted material.

The new dates support the idea that many asteroids experienced high energy crashes between 4.40 billion years ago and 4.48 billion years ago.

The window of the Moon-forming impact could tell us how our own planet came to be.

More information: Walton, C.R. et al, Ancient and recent collisions revealed by phosphate minerals in the Chelyabinsk meteorite, Communications Earth & Environment (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-022-00373-1 Journal information: Communications Earth & Environment Citation: Microscopic view on asteroid collisions could help us understand planet formation (2022, February 23) retrieved 23 February 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2022-02-microscopic-view-asteroid-collisions-planet.html This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.