When we attached tiny, backpack-like tracking devices to five Australian magpies for a pilot study, we didn't expect to discover an entirely new social behavior.

To learn more about the movement and social dynamics of these highly intelligent birds, and to test the new, durable and reuseable devices, was our goal. The birds were smarter than us.

The new research paper explains that the magpies began showing evidence of rescue behavior to help each other remove the tracker.

This was the first instance in which we knew of a person helping another person in a group without getting a reward.

Testing new devices.

We are used to experiments going awry in one way or another. Expired substances, failing equipment, contaminated samples, and an unexpected power outage can all set back months or even years of carefully planned research.

unpredictability is part of the job description for those who study animals. We often need pilot studies because of this.

Most trackers are too big to fit on medium to small birds, and those that do tend to have very limited capacity for data storage or battery life. They are single-use only.

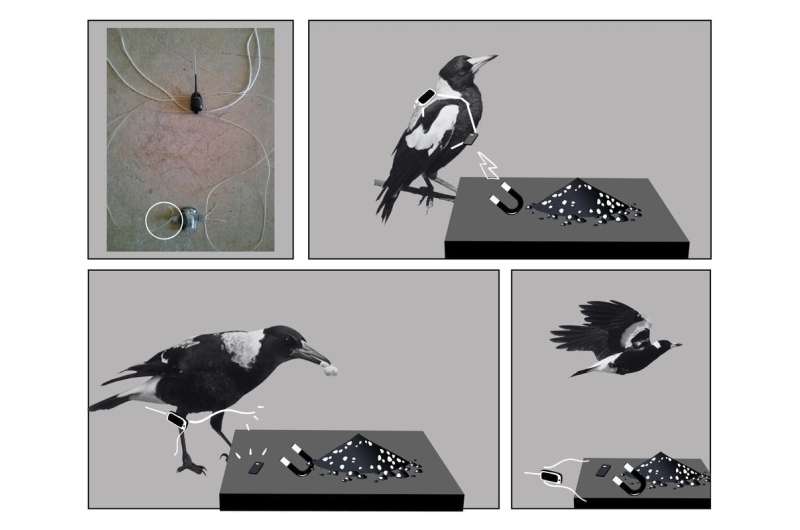

The design of the harness that held the tracker was novel. We came up with a method that did not require birds to be caught again to download data or reuse small devices.

We trained a group of local magpies to come to an outdoor, ground feeding station that could either wirelessly charge the battery of the tracker, download data, or release the tracker and harness by using a magnet.

The harness was tough and only one weak point where the magnet could work. The harness needed to be removed with a magnet or scissors. The design gave us many possibilities for efficiency and allowed us to collect a lot of data.

We wanted to find out if the new design would work and what kind of data we could gather. How far did the magpies go? Did they have a schedule for movement throughout the day? How did their age, sex, or dominance rank affect their activities?

We fitted five of the magpies with tiny trackers that weighed less than one gram. We had to wait and watch, and then lure the birds back to the station to get the data.

It was not going to happen.

The health, safety and survival of the group are ensured by the cooperation of animals. Cognitive ability and social cooperation have been found to correlate. Animals living in larger groups tend to have better problem-solving skills, such as spotted wrasse and house sparrows.

Australian magpies are no exception. It has adapted well to the changes to their habitat that humans have made.

Australian magpies live in social groups of between two and 12 people, and are known to occupy and defend their territory through song and aggressive behaviors. Older siblings help to raise young birds.

During the pilot study, we found out how quickly magpies solve a group problem. Within ten minutes of fitting the final tracker, we saw an adult female without a tracker working with her bill to try and remove the harness from a younger bird.

Most of the other trackers were removed within hours. The tracker of the dominant male of the group was dismantled by day 3.

We don't know if it was the same individual helping each other or if they shared duties, but we had never heard of any other bird cooperating in this way to remove tracking devices.

The birds needed to solve a problem by testing at pulling and snipping at different sections of the harness. They needed to help other people and accept help.

The only other example of this type of behavior we could find in the literature was that of the warblers in the islands. This is a very rare behavior.

Saving birds.

Most bird species that have been tracked haven't been very social or considered to be cognitive problem solvers. The tracker may be seen by the magpies as a kind of parasites that needs to be removed.

Climate change is making magpies vulnerable to the increasing intensity of heatwaves, which is why it's important to track them.

In a study published this week, researchers from Perth showed the survival rate of magpie chicks can be as low as 10%.

They found that higher temperatures resulted in lower cognitive performance. Cooperative behaviors could become even more important in a warming climate.

Scientists are always learning to solve problems. We need to go back to the drawing board to find ways of collecting more vital behavioral data to help magpies survive in a changing world.

This article is free to use under a Creative Commons license. The original article is worth a read.

Citation: Altruism in birds? Magpies have outwitted scientists by helping each other remove tracking devices (2022, February 22) retrieved 22 February 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2022-02-altruism-birds-magpies-outwitted-scientists.html This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.