The nation-state-backed exploits that can quietly and remotely hack into iPhones anywhere in the world are what you hear of today. Governments buy and operate powerful hacking tools that are used to target their most vocal critics.

The average person is more likely to be affected by consumer-grade spyware apps that are controlled by everyday people.

The term "stalkerware" is used for consumer-grade software that can be used to track and monitor other people without their consent. The apps are hidden from home screens but secretly uploaded to the person's phone with call records, text messages, photos, browsing history and precise location data. It is easier to install a malicious app on the phone than on the computer, which is why many of them are built for the operating system.

The private phone data, messages and locations of hundreds of thousands of people, including Americans, are at risk because of a consumer-grade security issue that was revealed last October.

It's not just one app exposing people's phone data. It is an entire fleet of apps that share the same vulnerability.

The vulnerability was discovered as part of a broader exploration. The vulnerability is simple and allows near-unfettered remote access to a device's data. Codero, the web company that hosts the back-end server infrastructure for the operation, and those behind the operation have kept quiet about the security flaw that was privately disclosed.

Those targeted probably have no idea that their phone has been compromised. With no expectation that the vulnerability will be fixed any time soon, TechCrunch is now revealing more about the operation so that owners of compromised devices can uninstall the spyware themselves, if it's safe to do so.

CERT/CC, the vulnerability disclosure center at Carnegie Mellon University, has published a note about the spyware, given the complexity of notifying victims.

The findings of a months-long investigation into a massive stalkerware operation that is harvesting the data from some 400,000 phones around the world, with the number of victims growing daily, include the United States, Brazil, Indonesia, India, Jamaica, the Philippines, South Africa and Russia.

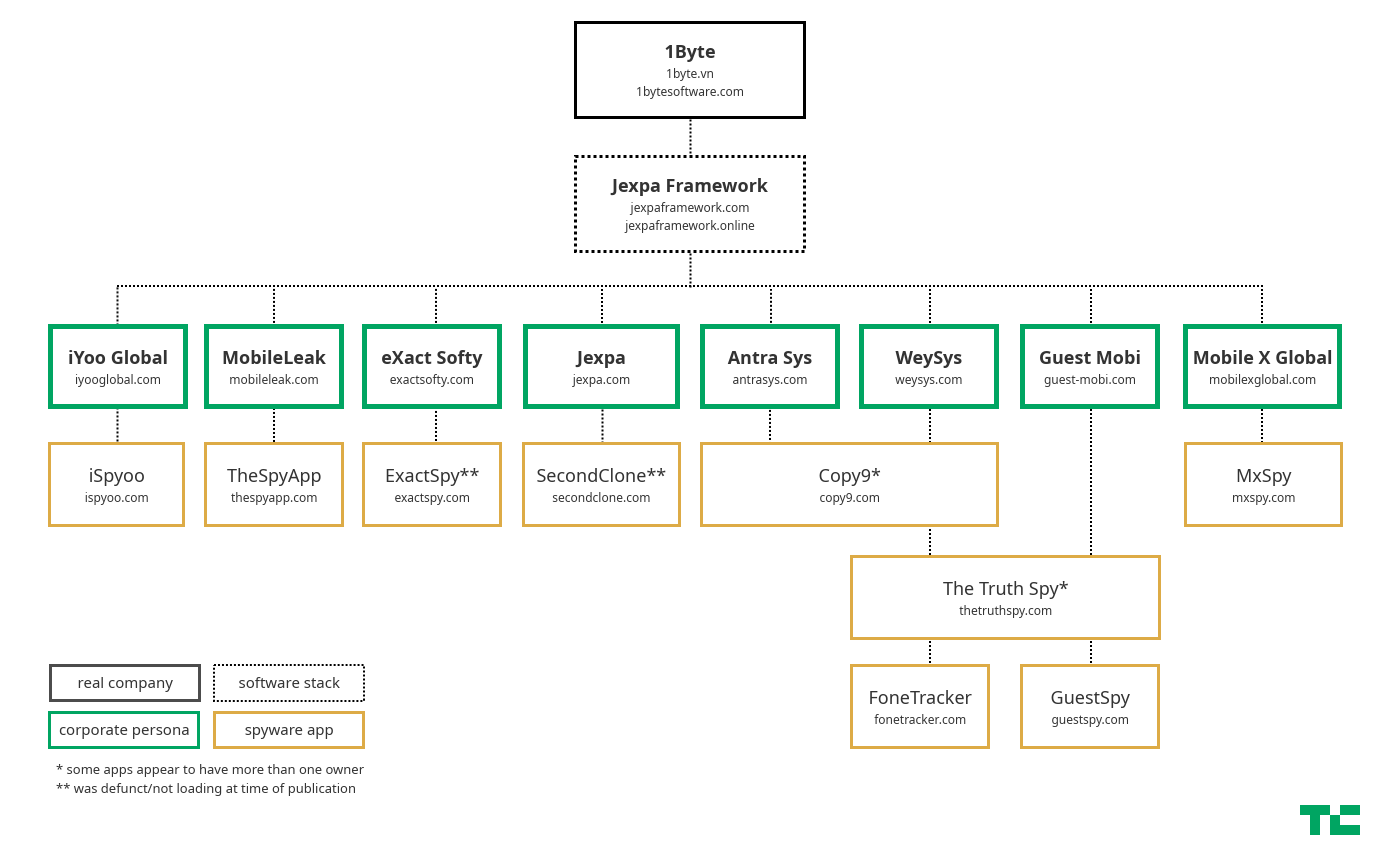

There is a collection of white-label Android spyware apps that continuously collect the contents of a person's phone, each with custom branding, and fronted by identical websites with U.S. corporate personas that offer cover. The operator of the server infrastructure behind the apps is known as 1 Byte.

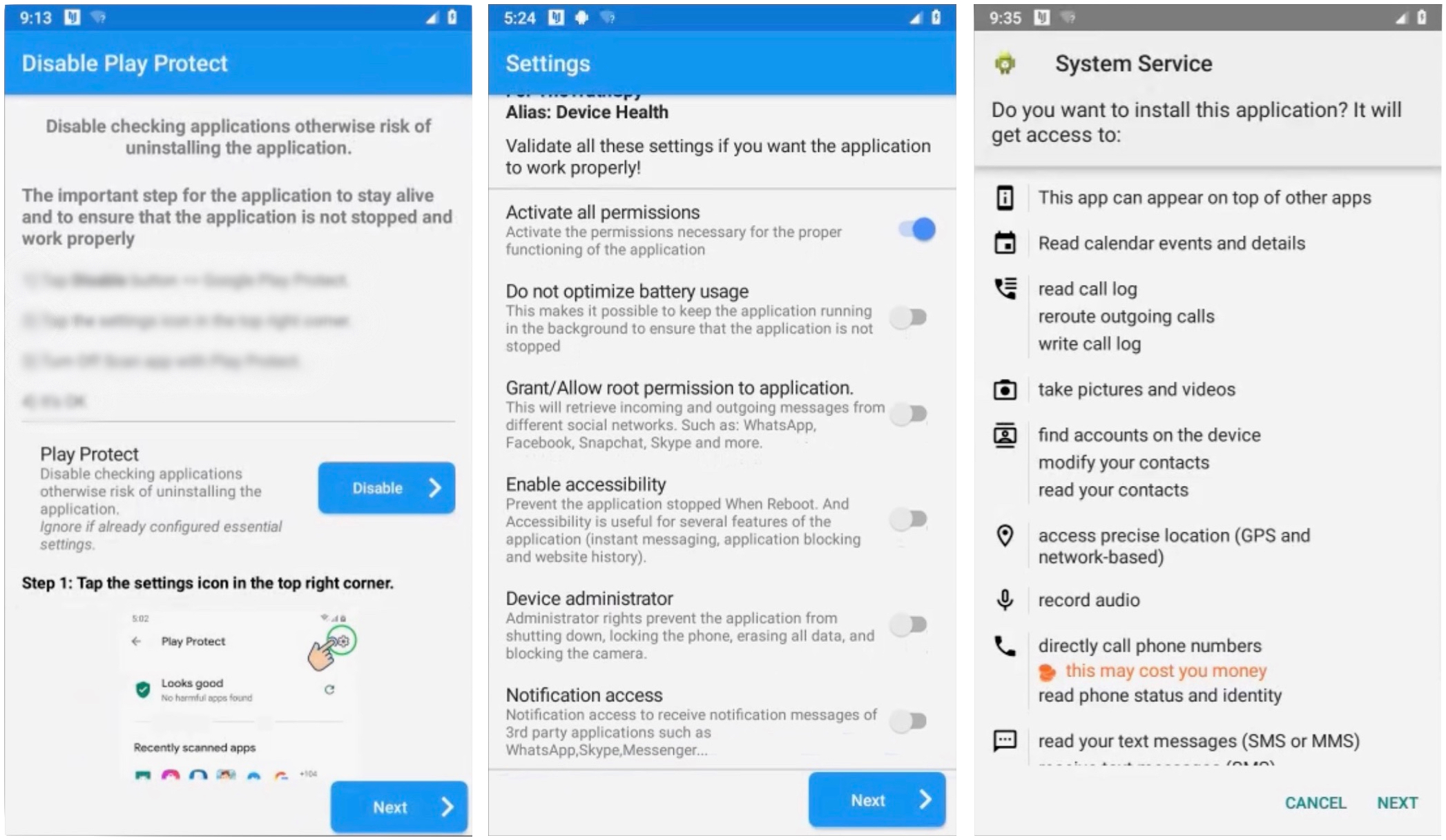

The user interface is used for planting spyware. The image is from TechCrunch.

TheTruthSpy, MxSpy, iSpyoo, SecondClone, TheSpyApp, ExactSpy, FoneTracker and GuestSpy were all found to be nearly identical.

The spyware apps have the same features under the hood, and the same user interface for setting it up. Once installed, each app allows the person who planted the spyware to view the victim's phone data in real time, including their messages, contacts, location, photos and more. Each dashboard is a duplicate of the same software. When we analyzed the network traffic of the apps, we found they all had the same server infrastructure.

Nine apps share the same code, infrastructure and infrastructure vulnerability.

The vulnerability in question is known as an IDOR, a class of bug that exposes files or data on a server because of sub-par, or no, security controls in place. It's similar to needing a key to open a mailbox, but that key can also open every other mailbox in your neighborhood. IDORs are one of the most common types of vulnerability, and have been found and disclosed before, such as when LabCorp exposed thousands of lab test results, and the recent case of CDC-approved health app Docket exposing COVID-19 digital vaccine records. IDORs have an advantage in that they can be fixed at the server level without having to roll out a software update to an app or a fleet of apps.

The private phone data of ordinary people was exposed by shoddy coding. More details about the operation are revealed by the bugs in the infrastructure. We learned that the data on some 400,000 devices has been compromised by the operation. Personal information about affiliates who bring in new paying customers and even the operators themselves were exposed because of sloppy coding.

Behind each branded app, web dashboard and front-facing website is a fake parent company with its own corporate website. The websites of the parent companies are identical and all claim to be software outsourcing companies with over a decade of experience and hundreds of engineers.

The parent company websites are all hosted on the same server if the identical websites weren't an immediate red flag. Current business records for any of the purported parent companies were not found in state and public databases.

Jexpa is a parent company. Jexpa does not appear to exist on paper, but for a time it did. In 2003 Jexpa was registered as a technology company in California, but it was MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE MzE The company's domain was left to expire.

The expired domain was purchased by an undisclosed buyer. There is no evidence of a connection between the former Jexpa and the purchaser of Jexpa.com. Jexpa.com is filled with stock photos and dummy pages and uses the likeness of several real-world identities, like Leonardo DiCaprio. The operators have gone to great lengths to hide their true involvement in the operation, including using the identities of other people to register email addresses, and using a photo of a former shipping executive.

1 Byte created a structure for the spyware apps. The image is from TechCrunch.

Jexpa is more than just a name. A set of release notes that was not meant to be public but had been left behind, and exposed on its server, were among the overlaps between Jexpa and the branded spyware apps.

The release notes describe the changes and fixes that have been made to the back-end web dashboard over the last three years. A developer with a Jexpa.com email address signed the notes.

The Jexpa Framework, the software stack running on its server that it uses to host the operation, each brand's web dashboard and the storage for the massive amounts of phone data collected from the spyware apps are all described in the notes. The source code for the Jexpa Framework was exposed to the internet just as they had done with the release notes.

The documentation laid out specific technical configurations and detailed instructions, with poorly redacted screenshots that showed portions of several domain and subdomains used by the spyware apps. The operator's own website was exposed in the same way. The documentation pages show how to set up new content storage server for each app from scratch, even down to which web host to use, as well as showing examples of the spyware apps themselves.

The operator put a lot of effort into making Jexpa look like the top of the operation. The operator left behind a trail of internet records, exposed source code and documentation that connects Jexpa, the Jexpa Framework and the fleet of spyware apps to a Vietnam-based company called 1 Byte.

The Jexpa Framework's documentation pages were put behind a password wall after we contacted 1 Byte about the vulnerability.

The small team of developers living and working outside of Vietnam's capital Ho Chi Minh City look like any other software startup. The group is enjoying the rewards of their work on its Facebook page. The same group of developers behind this enormous spyware operation that facilitates the surveillement of hundreds of thousands of people around the world are also behind 1 Byte.

The layers that were built to distance themselves from the operation suggest that the group is aware of the legal risks associated with running an operation like this.

It's not the only one that wants to keep its involvement a secret. The affiliates tried to hide their identities.

1 Byte set up another company called Affiligate, which handles the payments for new customers buying the software and also gets the affiliates paid. A small marketplace that sells mostly spyware was set up under the guise of allowing app developers to sell their software. 1 Byte seems to follow shoddy coding wherever it goes. The real identities of affiliates in the browser are leaking because of a bug in the marketplace.

Depending on where you look on the website, the company is either based in the U.K. or France. 1 Byte is listed as its Singapore office, but there is no evidence that it has a physical presence in Singapore. The U.K. company was struck-off by the U.K. registrar in March 2021. Daniel Knights was unsuccessful in locating and reaching him.

Only one other name appears in the paperwork. Van Thieu is the only shareholder of the company and he is located in London. Thieu is a shareholder of 1 Byte in Vietnam, and in his profile photo he wears a T-shirt with the 1 Byte logo. The director of 1 Byte is believed to be Thieu. Thieu is seen in several team photos on the group's Facebook page. The Jexpa Framework's code was left by one of the other 1 Byte employees.

The security vulnerability was sent to 1 Byte. We did not get a reply after the emails were opened. We followed up with 1 Byte using the email address we had previously messaged, but the email bounced and was returned with an error message stating that the email address no longer exists. We did not receive any replies to the emails that were sent to us.

At least two of the branded spyware apps stopped working after contacting 1 Byte and known affiliates.

We are here. Even if bad actors are to blame for the security vulnerability, the risk to hundreds of thousands of people is too great for the site to reveal.

If you believe it is safe to remove the spyware from your phone, we have put together an explainer. The person who planted the spyware will likely be alert to the fact that it is covert-by-design and could create an unsafe situation if they don't remove it. You can get help with creating a safety plan from the Coalition Against Stalkerware and the National Network to End Domestic Violence.

Despite the growing threat posed by consumer-grade spyware in recent years, U.S. authorities have been hamstrung by legal and technical challenges.

There is a gray area in the United States where the possession of spyware is not illegal. In rare cases, federal prosecutors have taken action against those who illegally plant spyware used for the sole purpose of secretly intercepting a person's communications. The U.S. government's enforcement powers against operators are limited at best, and overseas operators find themselves out of the reach of law enforcement.

Much of the front-line effort against stalkerware has been fought by antivirus makers and cybersecurity companies working together with human rights defenders at the technical level. The Coalition Against stalkerware was launched in 2019. Information about new threats can be given to other companies if the coalition shares resources and samples of known stalkerware.

After banning stalkerware apps from the Play store in 2020, the search engine blocked stalkerware apps from advertising in its results.

Federal authorities sometimes use novel legal approaches to justify taking civil action against operators, like for failing to adequately protect the vast amounts of phone data that they collect, often by citing U.S. consumer protection and data breach laws. The Federal Trade Commission banned SpyFone from the industry in the first order of its kind after it was found to have a lack of basic security that led to the public exposure of data on more than 2,000 phones. The FTC settled with Retina-X after it was hacked several times.

Recent years have seen a lot of headlines for spilling, exposing or falling victim to hackers who access vast troves of data.

An entire fleet of stalkerware apps can now be added to the pile.

The National Domestic Violence Hotline provides free, confidential support to victims of domestic abuse and violence. If you need help, call the emergency number. If you think your phone has been compromised, the Coalition Against Stalkerware has resources for you. You can reach this reporter by email at Zack.Whittaker@techcrunch.com.

Your Android phone could have stalkerware, here’s how to remove it