A collection of carved and polished spherical stones, each about the size of a cricket ball, will be on display in the British Museum. The stones are 5,000 years old and have mostly been found in Scotland. The most famous of the 400 or so discoveries is a beautiful polished black sphere from Towie, Aberdeenshire, with three tactile surfaces, as a miniature Henry Moore. The sphere is carved with whorls and spirals. The longer you look at the stones, the more mysterious they seem.

One thing that the balls and the culture that prized them make clear is that their creators were people of enormous curiosity and skill, prepared to invest untold hours in making a perfect object, because they could. They liked stone.

I was thinking about the ancient magic of those finds, and their more spectacular counterparts, while driving across Salisbury Plain last week with the British Museum's World of Stonehenge show in the background. The landscape has not changed since the bluestone and sar, with a trace of moon still visible, a thin mist lying in the valleys, and the morning light just beginning to ink in the curves of hills. The Salisbury Plain is the largest area of chalk grassland in northern Europe. Its rolling flatness and enormous skies demand some verticality, like the surface of the moon demanded a flag, and it is a monument that gives a sharp sense of identity to the landscape around it.

It is also a place made for sunrise because of its celebrated alignment with the sun during the winter and summer. The silhouettes of the oldest stones came more alive in the light and glow of a wintry dawn, borrowing the pinks and golds of the horizon. In this period of managed access to the site, to be in among the megaliths, in the absence of tourist crowds, felt like a lifetime privilege; in the quiet of the breaking morning, the building feels like an awesome natural receptacle for the new day. The double circle is designed to allow you to capture parts of the ruin without having to get the whole in your camera frame. The doors open up different ways as the show illuminates the monument.

The first earthworks at the site in 3000BC were the beginning of a series of interventions over the course of 1,500 years that included 90 truncated human generations. The constellation of ancient sites encircles the henge. The earthworks and settlements of nearby Durrington on the River Avon, the extraordinary stone circle and monumental ditch that runs through the centre of the village of Avebury, and the underground hilltop gravesite at West Kennet Long Barrow, approached over farmland. Most of the neolithic and bronze age treasures found by archaeologists and detectorists at such sites are housed in the two museums at Salisbury and Devizes.

This is the first time that the British Museum has devoted to this local history. It might seem timely and politic to have an exhibition devoted to this island's prehistory, as the museum is in repatriation arguments. The story is not that simple.

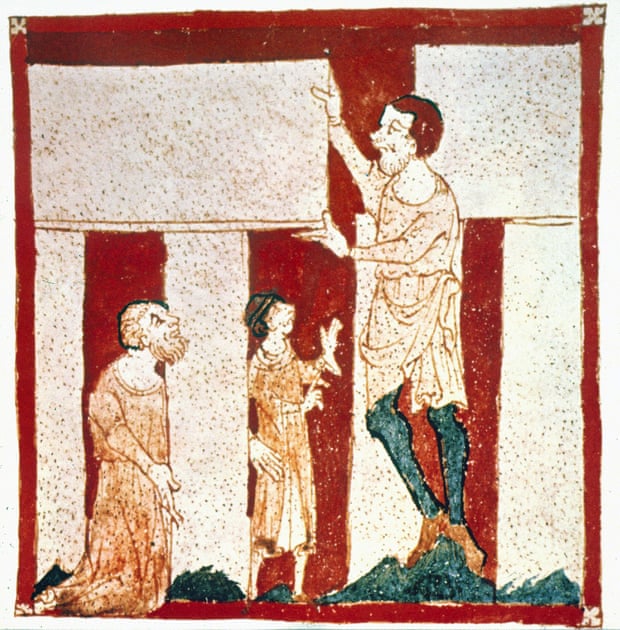

One 12th-century legend says that the wizard Merlin brought the rocks of Stonehenge to Britain. The rocks were first carried from Africa to Ireland by giants, and then removed by force by 5th-century British knights, according to the Historia regum Britanniae. The rocks were transported across the water by Merlin when the knights couldn't move them. Inigo Jones, an English architect, believed that the temple was a Roman temple, and John Aubrey, an antiquarian, believed that the Celts built it. William Stukeley imagined that druids would sacrifice themselves to the sun. TheSaxons, the Danes and the Egyptians were named as builders. By the late 19th century, the site had been dated to the bronze age. New age groups continued to lay claim to the site in the 20th century. In 1984, the association stuck, as Spinal Tap claimed that the legacy of the strange race of people, the druids, remained in the living rock of Stonehenge. The oldest known illustration of Stonehenge is in the 14th-century manuscript of a work by the Norman poet Wace. In the early 19th century, William Blake, JMW Turner and John Constable all marveled at the monument and explored its mythological resonances. In the 20th century, the Royal Navy named a destroyer and one of its submarines after Stonehenge, a symbol of British power and influence. The original function of Stonehenge has been a topic of debate for a long time. It has been thought of as a burial ground, a place of worship for ancestors, and a place of healing. The mystery of the stones and their hold on our imagination is as potent as ever. There is a person named Killian Fox.Quick GuideShow

I think people will think that this is a show about England, and then be surprised to find that, actually, to understand, you have to widen your focus.

The exhibition argues that the stones are best understood in the context of immigration waves. The first hunter-gatherer tribes who migrated north across the sea bridge to the Kent coast were from North Yorkshire. The first farmers came across the Channel 6,000 years ago, bringing with them seeds of cereals and sheep, and building the first stone circles. The Beaker people, named for their distinctive pottery, arrived from central Europe 1,500 years later and completely replaced the people who built Stonehenge.

The exhibition will give a shorthand story of all the population movements, focusing on the two millennia in which the first farmers on Salisbury Plain celebrated the sun and the seasons, and the period in which precious metals allowed the worship of golden light to be more personal and portable. The last exhibit in the show is a delicate sun pendant from the end of the bronze age in 1000BC. It was made by an Irish smithy. The decoration still has solar symbolism, but now the sun is setting.

The show will show how the mobile populations who have congregated at it for thousands of years have never had a settled meaning. In 1967, the archaeologist wrote that every age has the Stonehenge. At the 1985 Battle of the Beanfield, 537 new age travellers were arrested after clashing with Orgreave -hardened police over plans for a free festival. Scientific advancement has changed the structure of the monument. Celtic druids, who appeared about 2,000 years after the stones were erected, played no part in the creation of the monument.

The twin advances of radiocarbon dating and DNA analysis have changed our understanding of the societies that built the monuments. There is a whole new series of stories you can tell about a period of history which we have been taught to believe we know very little about, with a far more nuanced understanding of surviving objects. The forensic geology of an exquisite jadeitite axe head quarried in northern Italy and left as an offering beside the Sweet Track, a wooden pathway built through reed beds on the Somerset Levels in 3807BC, proves the movement of neolithic people over vast distances. Specific family relations are established by the testing of grave remains, giving a new human connection to the oldest bones.

The oldest, smaller, bluestone circle in Wales is where the most recent work on the stones by the archaeologist Mike Parker Pearson has identified. The location of the stones, weighing between two and five tonnes, was found by Pearson last year on a hill called Waun Mawn. In a book published to coincide with the exhibition, How to build Stonehen ge, the neolithic expert and British Archaeology magazine editor, Mike Pitts, documents the likely route by sea, river and land. The methods by which the great post-glacial sarsen megaliths with their unique lintels were hauled from the Marlborough downs and raised in place was surveyed by Pitts. According to new research, most of the stones were probably moved on enormous sledges across logs as rails, rather than on rollers, as was previously thought. It would take hundreds of thousands of man hours to shape and dress the stones.

The conclusion of his book is that the technology used to create the henge did not come from nowhere. There were many wooden structures of the same design across Britain and beyond. The British Museum show will include part of the outer ring of the Seahenge, a timber circle with a great upended oak tree. The 4,000-year-old bark of the Seahenge was exposed by rising sea levels in 1998.

A closer understanding of the lives of the people who built the henges and the people who moved the great stones suggests a high level of commonality and shared purpose. There are skeletons in the burial sites near the monument. The act of building may be as important as the building itself. Silbury Hill is the largest structure in Europe in 2400BC and is similar to the pyramids in Egypt. There is no tomb beneath the great mound. The latest theories suggest that it was a community effort and a monument to pastoral co-operation. The sarsen uprights of Stonehenge, and the long avenue that approached them, seem to have been constructed as this kind of society, with its deification of stone, was first beginning to come under threat.

The grave of the Amesbury archer, which was found in 2002 in a village three miles from Stonehenge, is an early example of this great technological and social shift. The man, who was in middle age, died 4,350 years ago and was buried with many objects, including five Beaker pots, three copper knives, a pair of gold hair ornaments, a small anvil used in metalworking and 122 pieces of worked flint.

The truth of the mix of grave relics makes him even more fascinating. The pots are likely to have been manufactured in the area where the Beaker style originated. The gold ornaments are made in a British style and probably came from mainland Europe. The Amesbury archer had grown up in the western Alps and traveled to Britain later in life, according to an analysis of his teeth. Archeologists conclude that this man was among the first to bring the magic of copper to Britain and that his burial was a high-status one.

The collective burial sites of the earlier period were more common in the centuries that followed. The appearance of metal objects, including gold, in these graves seems to coincide, the exhibition suggests, with new social networks and trading routes related to the ever-increasing demand for metal. Above ground, the implication of single-occupancy graves was mirrored. The implications of the new detailed DNA and dating advances are that the collective agrarian spirit that enabled it gave way to a more modern sense of individualism and selfhood. Cecil Chubb, a local born barrister, bought the property as a present for his wife in 1915. He gave it back to the nation in exchange for a baronetcy.

We talk about connecting a lot, but I think that we are using those connections to explain some of the fundamental issues.

There is a long period of competing traditions in which metal objects were made to celebrate and explain the movement of the sun and stars. The earliest such object in the world, the Nebra Sky Disc, is an exceptional loan to the British Museum from the Halle State Museum of Prehistory in Germany. The first-known depiction of the universe is a gold relief against a dark sky background. It is made of Cornish tin and gold and has astronomy knowledge from the Mediterranean and Egypt. The ideas that were once set in stone are now free to travel.