Two tiny fossils, each smaller than an aspirin pill, contain nerve tissue from 500 million years ago. The evolutionary history of modern-day spiders and scorpions could be better understood with the help of the bug-like Cambrian creatures.

Nicholas Strausfeld, a regents professor in the Department, said it was not clear where the fossils were.

The eyes and nerve cords of the animals can be seen in the fossils, but other parts of the nervous system are hard to see.

Strausfeld said that it is unclear whether the animals carry a brain-like bundle of nerves called a synganglion, and without this key piece of evidence, their relation to other animals remains fuzzy.

10 fascinating brain findings from dino brains to thought control.

The mess in the middle of the head is where the synganglion would sit. The researchers can tell that the mess is nerve tissue, but they can't tell what it is.

It is true that we do not have every single characteristic of the nervous system mapped out, because the fossils only tell us so much.

The researchers acknowledge this uncertainty in their new report, and present a few different ideas as to how these fossils relate to ancient and modern-day creatures. The place on the tree of life may eventually be resolved if more fossils are uncovered in the future.

The nerve tissue was found between 543 million and 490 million years ago.

According to a 2012 report in the journal Nature Communications, scientists discovered the first evidence of a arthropod brain about a decade ago.

More than a dozen Cambrian fossils have been found with preserved nerve tissue, most of them arthropods.

The fossils featured in the new study were found in the depths of the museum collections at the Harvard University Museum of Comparative Zoology in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the Washington, DC, museum.

The Harvard fossil is about 13 inches long and 3.5 inches wide and is oriented so that you can see the arthropod from above.

The side-view of M. symmetrica is offered by the fossil from the Smithsonian.

There are 8 rare and unusual fossils.

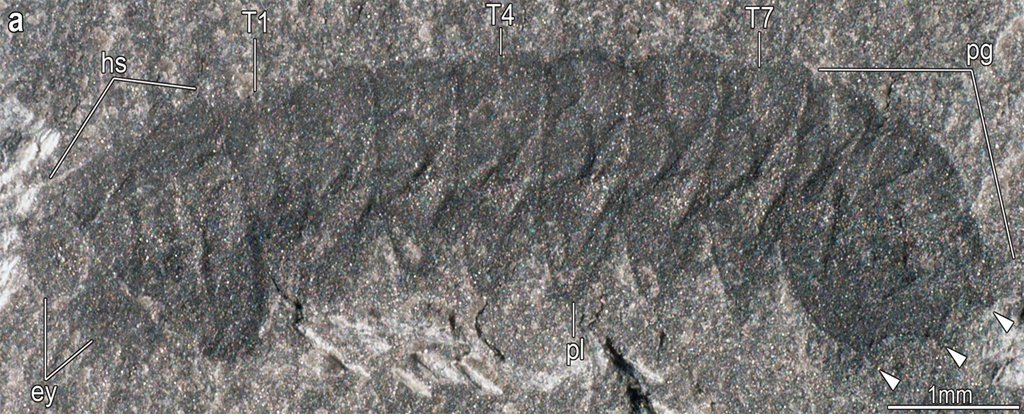

There is a view of a fossil. Ortega-Hern et al., Nat Commun., 2022.

Neither fossil looks particularly exciting to the naked eye. He said that the minuscule Smithsonian fossil is extremely unremarkable.

The M. symmetrica has a head shield, a trunk, and a shield on top of it.

The researchers think that the arthropod had seven pairs of appendages, two fangs, and six pairs of limbs, based on a fossil from a different species.

The fossils used in the new study lack appendages, and are highly unusual to find with intact limbs.

He spotted something intriguing when he put the fossils under a microscope.

He found that the arthropods were well-preserved. The nerves look like they have been fossilized and turned into carbon.

A nerve cord can be seen running down the length of the arthropod's belly, with some nerves jutting out from its underside. In the Harvard specimen, one can see two huge, orb-like eyes on the head, and a bit of the nerve cord peeking out from beneath the animal's digestive tract, which obscures the rest of the cord.

Strausfeld said the evidence for the nerves that run from the arthropods' eyes to the main body is ambiguous, and ideally, these features would be clearer.

We can see that there is something in there, but we don't have enough resolution to say that it is organized in this way or that way.

The relationship of M. symmetrica to other animals is murky because of the uncertainty in the fossil record. The team constructed two evolutionary trees based on the features of the arthropods.

The trees show that the ancient animal had a relatively simple nervous system that gave rise to the brain seen in modern-day members.

The megacheirans, one of the important arthropod groups from the Cambrian, have similar nervous systems to the modern ones.

There is a view of the Harvard M. symmetrica fossil. Ortega-Hern et al., Nat Commun., 2022.

Depending on where these various groups sit on their evolutionary tree, their placement either shows that the brain evolved in a stepwise manner through time, or that the nervous system evolved independently and at different times in some arthropods.

Strausfeld said he would be cautious about placing M. symmetrica anywhere on an evolutionary tree. He said he would need clearer evidence of how the arthropods' nerves are structured, as well as evidence of nerves extending out to the roots of the animal's limbs.

Strausfeld said that one needs a better preparation, a better specimen, than the ones examined so far.

There are related content.

There are 9 strange spiders.

The skull is nearly complete.

The oldest Homo sapiens fossils have been found.

The article was published by Live Science. The original article can be found here.