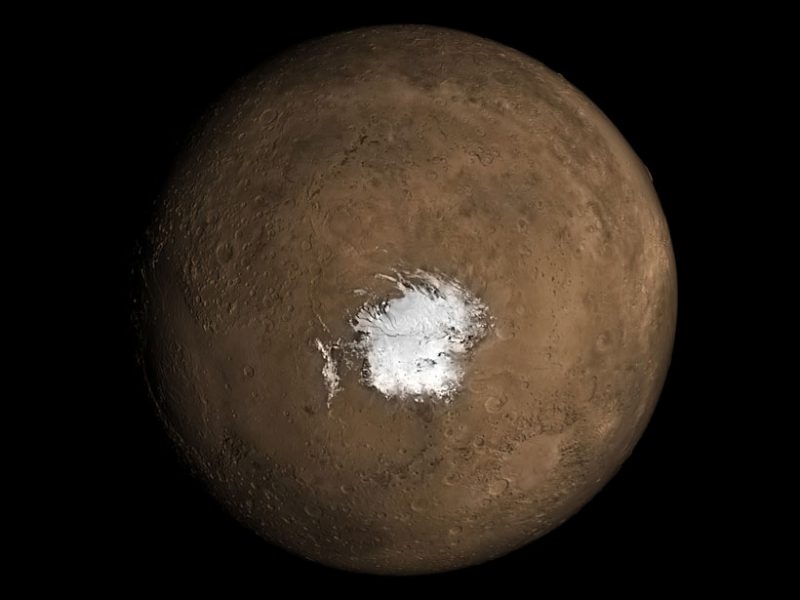

There was surface water on Mars a long time ago. Most people interested in Mars think that it's underground and probably frozen.

There is evidence that there is a lake of liquid water under the South Pole. Other evidence does not agree with it. What is going on?

Science is what.

Is there a lake on Mars? Each study arrived at a different answer after tackling the question. One confirms and the other refutes it. What do people think about this?

It might look like scientists don't know what they're doing, but that's not true. The scientific method is being played out in real-time.

We are used to simple yes or no answers, but that is not how things are. The Earth is round, right? It wasn't always this way. Everyone had the same evidence, but it took a lot of arguments before people realized that the Earth is a sphere. Earth is an oblate spheroid.

Nature hides the truth and things aren't always straightforward.

“I’d really like to know if brines do or do not exist under the SPLD, but uncertainty rules the day!”

Dr. David Stillman, Geophysicist, Southwest Research Institute.

We can look at the underground lakes around Mars. We have to rely on satellites to gather evidence. The data has to be understood. The interpretation is hard to understand.

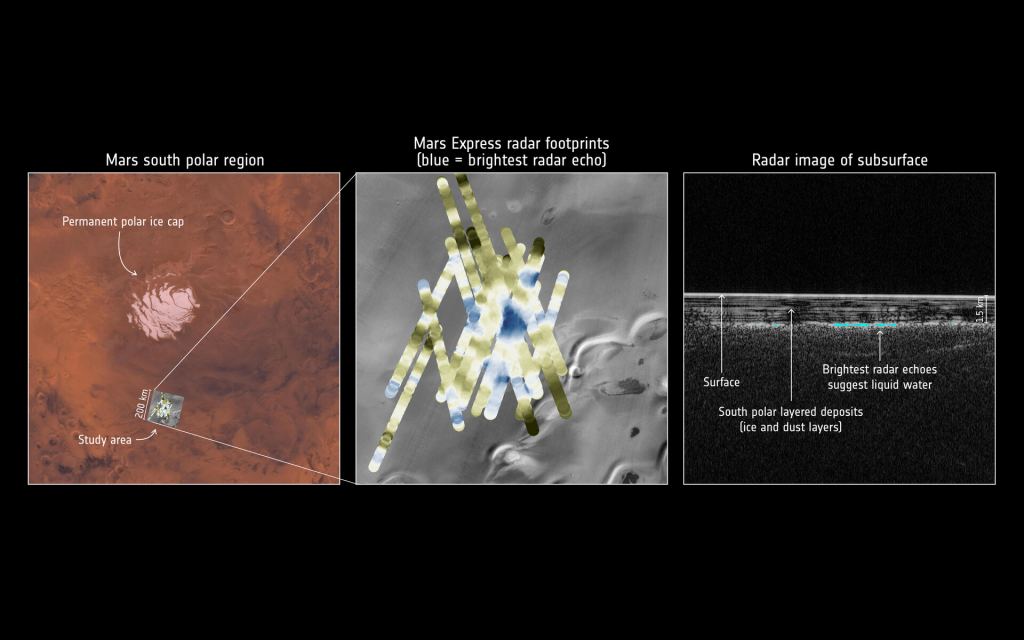

There was radar data from the Mars Express that suggested an underground lake near the south pole. The discovery was reported in the journal Science. The scientists concluded that it was water, or more accurately, brines, after analyzing the 20 km long reflective subsurface zone.

The lake is buried 1.5 km below the surface and resists freezing. It is similar to lakes found in northern Canada, and NASA found salts on Mars that could keep the lake from freezing. There were reasons to believe that the findings were plausible.

Some people were skeptical of the discovery. Jeffrey Plaut, a planetary scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said that it was not a slam dunk yet.

In 2020 another study confirmed the presence of the lake and found additional lakes. What they thought was lakes. The reflective surfaces were buried. The study generated more excitement because it might support simple life on Mars.

The reflective surfaces could be clays. The scientific was in full swing. Where is the issue now?

Two new studies come to different conclusions. Will one of them bring this issue to an end?

The original discovery of liquid water under the south pole could still be correct according to a new research letter published in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters. The title is Assessing the role of clay and salts on the origin of MARSIS bright reflections. The original paper showing the presence of liquid water under the southern polar region was written by Mattei and co-authors. The initial discovery of a lake is the subject of this letter.

The instrument on the Mars Express has detected the issue. The device is called MARSIS. It searches for frozen water on Mars. Liquid water is more reflective than frozen water.

The paper announcing the presence of buried liquid water was based on MARSIS data. The basis for the papers that arrive at different explanations for the measured reflectivity is also here. The data isn't in doubt, just the interpretations and scientific inquiry around it.

There is no liquid water, according to the research.

The Planetary Science Institute has a senior scientist named Nathaniel Putzig. Putzig is one of the authors of a paper. It is not necessary to use liquid water at the base of the polar cap to explain the MARSIS observations. Some metallic minerals, clays, and salty ice are alternatives.

The new research letter doesn't agree. The counter-explanations for the MARSIS signal are acknowledged by the authors. They discount clays, metallic minerals and salty ice as explanations.

A scientist at the Southwest Research Institute did lab experiments that were used in the new research letter. David Stillman, a co-author of the new research letter, conducted laboratory experiments on ice-brine mixtures at low temperatures.

There are lakes of liquid water underneath glaciers in the polar regions, so we have Earth analogues for finding liquid water below the ice. We studied how these salts would respond to radar.

The research showed that we don't have to have lakes of perchlorate and chloride brines, but that these brines could exist between the grains of ice or sediments. This is similar to how salt in the water saturates sand at the shoreline or how the taste of a slushie is different on the South Pole of Mars.

The issue is related to temperature. We don't know what the temperature is on Mars. If the water is briny, it can remain liquid at lower temperatures. The permittivity of different materials is affected by the temperature.

The authors wrote a paper about the different types of clays on Mars and how they appear in MARSIS data at different temperatures. The hypothesis that clay can generate a dielectric contrast with the SPLD large enough to obtain bright echoes is not supported by the fact that very low temperatures, such as those commonly inferred at the base of the SPLD (200 K), are totally inconsistent.

The cause of MARSIS bright reflections is not salty ice, but the brines of Ca and Mg that are found at Mars.

The clay samples were subjected to extremely low temperatures in the lab.

The temperature problem was discussed by Dr. Stillman on Universe Today.

The temperature behind the SPLD is critical. Stillman said that their understanding of the temperature was poor. It is more complex than a single sheet of ice.

Scientists don't know how the SPLD affects temperature uncertainty.

Are there lakes below Mars? We don't know. It might be more slush than a lake, and it might not be a lake at all.

The power of the scientific method is shown in this back-and-forth. They are just engaging with the evidence and reaching different conclusions.

This is how the scientific method works. It is frustrating to see papers that are very different from each other. Cyril Grima is a planetary scientist at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics. In a separate article, Universe Today will cover that paper.

VID plays a role as well. In normal times, scientists would discuss issues like this at conferences and share their ideas and lines of inquiry. Face-to-face discussions at conferences don't guarantee consensus, but they are a part of the scientific process.

Some of this is due to the lack of in-person conferences due to COVID, Stillman said.

I don't know which assumptions are correct because we are studying a planet so far away.

We need better data before we can agree. It is frustrating for researchers and the rest of us who are interested in Mars, water, habitability, and the host of issues that ride shotgun alongside Martian water.

It is a fascinating look at the scientific method that is being used.

I would really like to know if brines exist below the SPLD. I think partially saturated brines are the most correct answer, but I can't be positive. This is what makes science fun.