According to a small new study, a widely-used cancer drug that works on the immune system may be able to push HIV out of hiding.

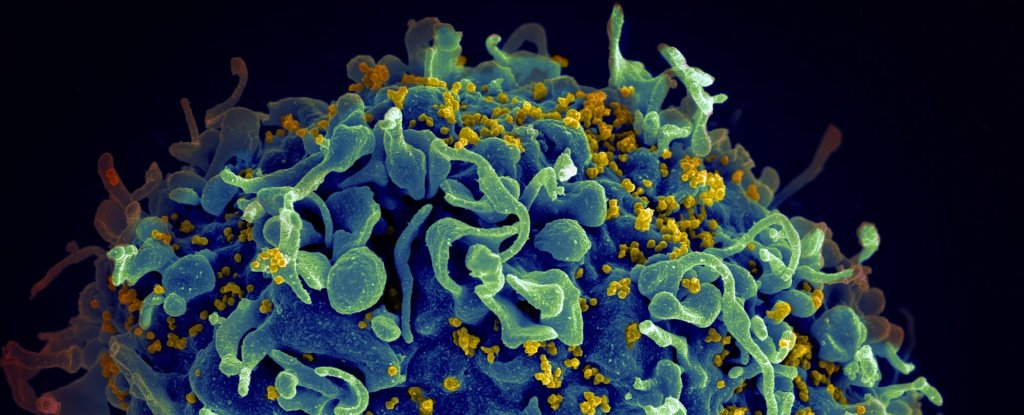

The human immunodeficiency virus is known for its ability to evade the immune system. It can escape detection by hiding its genetic material inside long-lived immune cells.

This has been a major roadblock to developing a cure for HIV, as the virus is still present in the body even after a cure is achieved.

A new study suggests that pembrolizumab, an immunotherapy drug which has transformed the treatment of melanoma and other cancers, might also be able to reverse HIV latency.

The trial was only small, featuring 32 people living with both HIV and cancer, and the results are very exciting.

Pembrolizumab works by reactivating worn-out immune cells that express a bunch of proteins on their surface. Lewin and colleagues have shown that HIV co-opts these markers to sneak into hibernation and lie undetected.

T cells that seek and destroy cancer cells are awakened by blockingPD1 with pembrolizumab. Researchers wondered if the drug could bring the HIV out of hiding and unlocked the dormant immune cells.

Until now, there have only been a few case reports showing that pembrolizumab might flush HIV out of immune cells in people with HIV, because they have an increased risk of developing cancer.

The drug did not eradicate HIV in the study, but the result Informs efforts to manipulate T cells to cure HIV, according to Thomas Uldrick of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Blood samples were collected from participants before and after treatment with pembrolizumab, and the samples were analyzed to see how much of the virus was in the blood.

Although most people in the trial still had undetectable levels of HIV in their blood, the researchers found evidence that a week after the first treatment, a modest but significant level of the virus had been coaxed out of hibernation and started replicating again.

More research is needed to figure out how anti-PD1 drugs affect the immune response and act on HIV-specific T cells. Lewin says that the team is pursuing these questions in the hope that it will also kill the HIV-infected cells in the way it kills cancer cells.

There is potential for this and other similar treatments to develop a pathway towards a pragmatic HIV cure, according to a Kirby Institute researcher. He wasn't involved in the study.

Lewin believes that immunotherapies could form part of a multi-pronged treatment approach that she hopes could help the nearly 2 million people diagnosed with HIV every year.

Researchers will need to further investigate and weigh up the drug's known side effects, which may be tolerable for people with a life-threatening illness such as cancer, but have thus far been a barrier to testing immunotherapies in otherwise healthy people living with HIV.

Lewin says that people with HIV can now live normal and healthy lives.

Lewin says that the researchers are about to embark on another trial looking at the effects of anti-PD1 therapy on blood cells and lymph nodes to try and find the lowest, safest dose for people living with HIV who don't have cancer.

Science Translational Medicine published the current study.