A frog has regrown a lost leg after being treated with a cocktail of drugs.

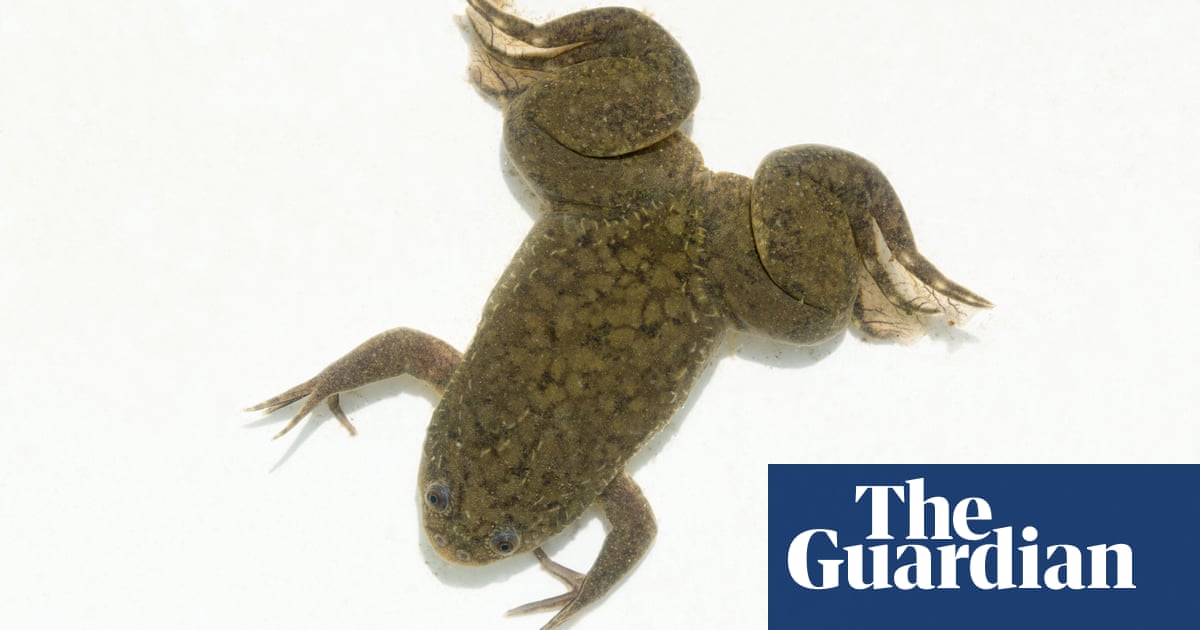

The African clawed frog, which is unable to regenerate its limbs, was treated with drugs for just 24 hours and this resulted in the regrowth of a leg. The demonstration raises the possibility that in the future drugs could be used to restore tissues lost to disease or injury in humans.

Nirosha Murugan, the first author of the paper, said that it was exciting to see that the drugs they selected were helping to create an almost complete limb.

salamanders, starfish, crabs and lizards are some of the creatures that are capable of regenerating limbs. Flatworms can be chopped into pieces.

Children can grow the tips of their fingers after being halved and the human's body can grow back to full size after being halved. Natural processes in mammals can't restore the loss of a large limb. The formation of scar tissue protects us from blood loss and infections.

In the latest research, published in the journal Science Advances, scientists sewed a wound in a frog's hind-leg with a five-drug cocktail. The drugs have different purposes, including reducing inflammation and stopping scar tissue from growing. New nerve fibres, blood vessels and muscle were promoted by the drugs.

The experiment was repeated in dozens of frog and many of them had regrowth of tissue, with many re-creating an almost fully functional leg, including bone tissue and even toe-like structures at the end of the limb.

The regrown limb moved when it was touched, and the frog were able to use it for swimming.

In the first few days of treatment, scientists observed the activation of pathways that are normally used to map out limbs in the embryo. They believe that adult humans still have the information needed to make body structures and that it should be possible to use this ability.

The right drug cocktail and covering the open wound with a liquid environment under the Silicone cap could provide the necessary first signals to set the regeneration process in motion. The technique will be tested in mammals.

Bob Lanza, head of Astellas Global Regenerative Medicine, who was not involved in the research, described it as an amazing achievement.

The study has exciting ramifications for the field of regenerative medicine. With the right combination of drugs and factors, a similar approach could potentially spur regeneration and restore lost function in humans.

The pig-to-human heart transplant is only a last resort.

Michael Schneider, a professor in cardiology at Imperial College London, said that the findings could have applications in other areas of regeneration, such as the possibility of scarless healing after a heart attack.