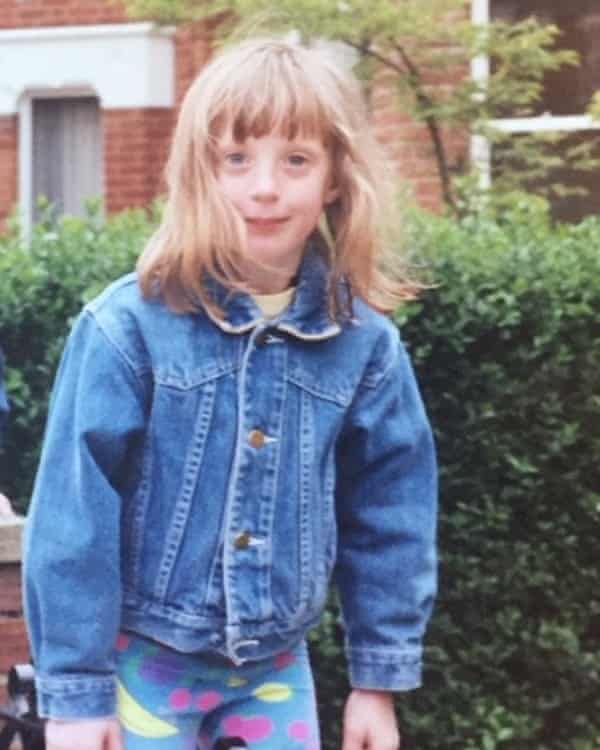

Kitty Wallace remembers the first time she felt a problem with her face.

She remembers looking at her reflection and thinking how different she looked to her.

The belief in the wrongness of her face grew stronger and stronger. By the time Wallace reached her teens, she had become paranoid about public humiliation.

She says that the fear of being made fun of was overwhelming.

At the time, Wallace didn't know that she was suffering from body dysmorphic disorder, a condition that causes a preoccupation with perceived defects in your appearance, often causing self-consciousness and fear of social rejection.

Wallace is one of the UK's leading advocates for BDD, using her own battle to raise awareness of this often misunderstood and still largely hidden illness. A study estimates that BDD affects about 2% of the population, which is about 50 people.

She says that despite celebrities talking openly about their struggles with BDD, there is still barely any understanding of what this condition is. People are not getting help or treatment that they need. Most people don't get a diagnosis for at least 10 years.

Wallace sees her story reflected in the struggles of people who have BDD, as the head of operations for the BDDF.

It was an overwhelming belief that there was something wrong with the core of who I was.

Wallace is the charity's main staff member, she also manages the website and facilitates support groups.

I went to the first BDD conference in 2016 as an attender, and then the next year I organised the conference.

Wallace felt a huge sense of compassion for everyone who was brave enough to attend. She was 19 when she was diagnosed. I lost a lot of years to BDD and it still affects my life today. Nobody should have to go through that.

She says that BDD is one of the biggest problems, because it can manifest in late childhood or early adolescence when many people are going through emotional and physical upheavals.

She now sees that the signs were there all the time. She struggled with acute anxiety as a small child and never felt comfortable in herself or in the world. She has many tendencies associated with obsessive compulsive disorder that she now sees as signposts to her BDD.

I remember being very young and being obsessed with my clothes being clean, even the smallest mark would mean I had to change. I felt like people would think I was dirty and disgusting if I spilled something on myself.

She had short hair and glasses when she was sent to an all-girls boarding school at the age of 12. She says that it made her the focus of a lot of attention and that there were constant comments on her appearance. I had to find ways to make myself and my face acceptable.

Wallace had a lot of makeup sessions every day. She spent two hours on her makeup before she was able to leave her room and go to breakfast.

I would eat breakfast quickly, run back up to my room to check my makeup, and then go back to class to check it out. I didn't let it slip for a while. It was tiring and lonely.

Her BDD shifted her focus from her hair to her skin, as well as spending hours on makeup routines. The thought of a whitehead on my face was torture.

Wallace's nose became a source of fear and shame. I hid behind a fringe that was my security blanket for years, trying to keep my face out of the public eye.

Wallace says that many students with BDD drop out of education altogether. A study found that almost 60 percent of young people with a diagnosis of BDD were either not attending school at all or only intermittently.

The risk of suicide among those with the condition is 45 times higher than the national average, according to a study. She says that if it weren't for the support of her family, she wouldn't have survived.

She says that many people have lost their lives because they don't know what BDD is. Many people alter their faces through multiple surgeries and get very limited and painful lives.

When Wallace heard about BDD, she had finished school and was living in self-imposed seclusion at her family home while her friends took gap years and attended universities across the country. Her brother got a call. He said that he thought the documentary was wrong for your sister.

Her mother found it online. Wallace felt like someone had crawled inside her brain and written down everything they could find when she read the BDD symptom checklist on the website. The idea that I had a condition, that it wasn't my fault, was a huge weight off my shoulders. For years, I blamed myself for everything.

One of the only BDD clinics in the country was run by the Priory. She was referred to Dr Rob Wilson, a cognitive behavioural therapist who works on BDD and the co- founder of the BDDF.

Going into treatment was tough at the beginning, but soon I was having huge moments. She says that she clipped her fringe back for the first time and was able to walk down the street.

It has not been a straight line towards recovery. Wallace relapsed after she developed a red rash on her face. I wouldn't sit in the back garden if the neighbours saw me.

Wilson told her that most of the funding came from In Memoriam donations from families who had lost children to the condition.

Three years after Wallace started volunteering, he became the first paid staff member. Hundreds of people with BDD have been helped by a dedicated email helpline that she launched after securing lottery funding. The number of visitors to the website has more than doubled this year to 500,000. She says that it's frustrating because they are a small charity and they are struggling to cope with the numbers asking for help.

She co-facilitated monthly face-to-face support sessions for people with BDD. They stopped meeting in person but started weekly online sessions.

She says that facilitating these groups is one of the most rewarding parts of her job. You can see that person change when they realize that they are in a safe place and that they don't need to apologize or explain their actions. There is no judgement.

There is a constant bombardment of images of people looking flawless on social media, with no transparency about how much these pictures have been altered.

Wallace helped launch a partnership between the BDDF and the fashion brand Monki, lobbying for EU legislation that would see brands and social media users legally required to put a notice on advertising or social media posts that had been altered or filters. More than 30,000 people have signed their petition since it was launched three weeks ago.

The campaign with Monki is important because it gets awareness of BDD out to a huge number of people and this could save lives.

Even though my BDD is still with me, I'm getting married next year and these things seemed impossible a few years ago. I want people with BDD to know that they are not alone.

More information about the petition can be found on the bdd foundation website.

Samaritans can be reached in the UK and Ireland by email or phone. The National Suicide Prevention Hotline is in the US. The crisis support service in Australia is 13 11 14. There are other international helplines at befrienders.org.