Five years ago, I met John Grunsfeld outside of a coffee shop in Houston, across the street from Johnson Space Center.

He retired from NASA after a long career. Over the course of nearly two decades, Grunsfeld had flown into space five times, the last three of which were missions to service the Hubble Space Telescope. He was affectionately known as the "Hubble Hugger" for his work on the venerable instrument in space.

He was the associate administrator of the agency's science directorate after leaving the astronaut corps. We met in the fall of 2016 and he was back to his private life. I wanted to know what Grunsfeld thought about the science priorities of the space agency. He was in Houston for his annual physical for astronauts, and we enjoyed the late November sunshine as cars drove by on NASA Road 1.

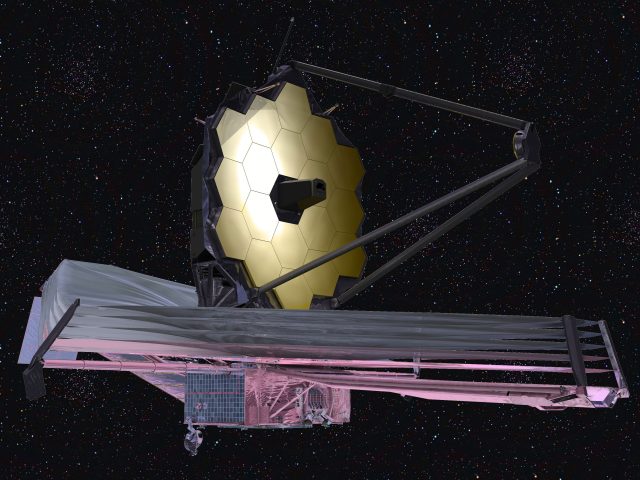

We talked about a lot of topics, but the one that stood out to me was the few minutes we talked about the James Webb Space Telescope. The deployment process in space had hundreds of single-point failures, and that's what Grunsfeld was worried about. He said that many things could go wrong. He thought something would go sideways and then where would NASA go next to ask for money for a project?

As I spoke with other scientists and engineers over the years, they all offered variations on the same theme of concern. It began to appear that something could go wrong during the deployment or the transit to a lagrange point 1.5 million kilometers away. I wondered if the telescope would launch. None of the successors would want to assume the personal risk of failing on their watch.

Something miraculous happened after that. The James Webb Space Telescope was launched on Christmas morning of 2021. The associate administrator for science at NASA made the call. He would take the blame if he failed.

The Ariane 5 rocket performed the flight with such precision that it was able to save precious fuel for maneuvering and extend the lifetime of the craft. Engineers and scientists worked for two weeks to extend the telescope and its sun shield. On Monday, the spacecraft performed one final major burn of its thrusters, falling into a halo around the L2 point.

This means that the telescope has reached its final destination and will stay in line with the Earth as both the telescope and planet travel around the Sun. While using a minimum amount of fuel to hold its position, the sun shield can be used to keep the telescope and instruments cold.

The work is not done. The telescope has 18 primary mirror segments. They have been shown to work and have already been tested. Over the next three months, telescope operators will fine-tune the alignment of these mirrors. Scientists will use a Sun-like star to focus the mirrors. The star can be found in the center of the Big Dipper.

In order to be able to detect the faint signals of heat from the Universe's oldest galaxies, the mirrors and their scientific instruments will have to cool down.

It is difficult to believe that this is happening. The entire space science project is complete, and now the instruments should be routine. The odds are very high that it will get there.

I have only been an outside observer of this process for the last five years, but I am concerned about the fate of this $10 billion telescope, but not facing any serious consequences should it fail. I have been worried about the fate of the man for a long time. I have been discouraged about making a science observation. Over the last couple of weeks, everything has fallen into place and I have been happy.

I can only imagine the joy of the scientists who worked on this project. To all of you, a big thank you.