CDn.vox-cdn.com has achorus image.

After traveling hundreds of thousands of miles through space over the last month, NASA's revolutionary new James Webb Space Telescope performed its last big course correction maneuver this afternoon, putting itself into its final resting place in space. The observatory will live for a long time at a distance of 1 million miles from the Earth.

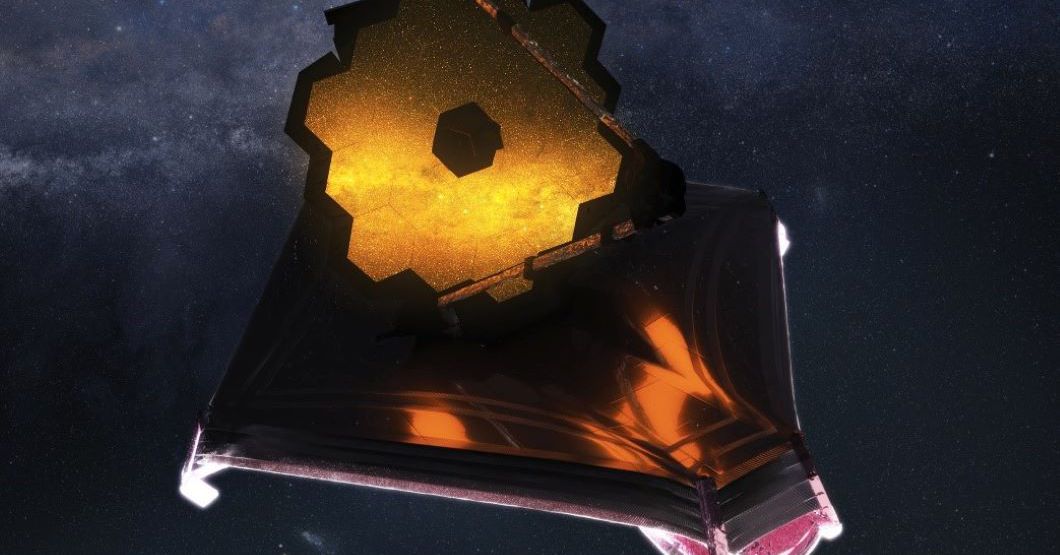

On Christmas Day, NASA launched the James Webb Space Telescope, or JWST. The telescope had to be folded up in a rocket to fly to space. When it reached space, the JWST began an extremely complex routine of shape shifting and unfurling, a type of choreography that had never been done before. The major deployment of JWST was completed on January 8th and it blossomed into its full configuration.

You can live in perpetuity at 1 million miles from the Earth.

One failure could have jeopardized the entire mission, as they had to work as planned. When unfurling was over, the mission team was still uneasy. In order to do its job properly, JWST had to get into its final position in space. If the observatory didn't slow down just right today, the vehicle would be at risk of missing its target trajectory. It would have been difficult for scientists to communicate with the nearly $10 billion space observatory if the mission had failed.

The last maneuver was performed perfectly by the JWST. Bill Ochs, the project manager at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, said in a statement that the project has achieved amazing success and is a tribute to all the people who have worked on it.

It didn't take long for JWST to get to its final destination. The onboard thrusters were fired for about 5 minutes. It was the last of three course correction burns that the JWST has done, slowing the craft down enough to put it into a very precise position in space.

The Earth-Sun lagrange point is an invisible point in space. There is a place in space where the gravity and centripetal forces of the Sun and the Earth are just right, allowing objects to remain in a relatively stable position. Jean-Paul Pinaud, the lead of the ground operations at the primary contractor of the JWST, says there is a tug of war going on wheregravity balances out perfectly. Nobody wins that tug of war.

There is a tug of war going on.

The Earth and the Sun share five of these points. There are two planets in between the Earth and the Sun and one on the opposite side of our star. L2 is a Lagrangian point located on the far side of the Earth further from the Sun. As Earth moves around the star, the JWST will follow the planet almost in lockstep, like a constant companion. No matter where Earth is on its course around the Sun, it will be a million miles away from us.

The distance between the Earth and the Moon is roughly the width of the track that the JWST is taking around L2. The observatory needs some help to stay on that trajectory. L2 is known as a pseudo stable, meaning objects that are in this location will drift away in one direction. Pinaud says it is like sitting on a saddle of a horse. You are stable on a saddle of a horse. Imagine yourself as a marble, from head to tail, you will probably roll down to the center, but then you will fall to the ground if you go to either side of the saddle.

Noupscale is a file on thechorusasset.com.

Over its lifetime, JWST will have to make small adjustments to its path. Every 20 days or so, the telescope will fire its thrusters for two to three minutes at a time to make sure it stays on track. How long the JWST can stay in space will be determined by these adjustments. The observatory's mission will end when the propellant runs out in the next 20 years. The Ariane 5 rocket put the telescope on such a great trajectory that it will last longer than expected.

It may seem like a lot of work is needed to keep it stable. For a variety of reasons, L2 is an attractive place for this observatory. It is far away from the Earth and the Sun. A type of light that is associated with heat was collected by JWST. The telescope must be very cold at all times. It has a sun shield that will always be facing the Sun, a protective umbrella that will reflect the star's heat, and a telescope that is extra cold. If NASA isn't careful, any nearby object emitting heat and light could muck up the observations. NASA is guaranteeing that the light from the Earth and the Moon won't interfere with the telescope.

L2 is an attractive place for an observatory.

L2 is great for power because one side of JWST will always be facing the Sun. The telescope has a solar panel that gathers sunlight for power. The Hubble Space Telescope doesn't have that luxury. Hubble has to store power in its batteries when it is on the night side of Earth. That will not be the case for JWST. Kyle Hott, the mission systems engineering lead for JWST at Northrop Grumman, says that they don't have to worry about any eclipses.

Extreme fluctuations in temperature can cause a spacecraft's instruments to degrade over time, and there are other drawbacks to constantly changing between day and night. Throughout its lifetime, JWST will operate at the same temperatures.

There is a benefit to continuous communication. With L2 always in the same position relative to Earth, JWST will be a set distance away from our planet at all times. We can be in constant contact with the observatory. Hott says that they can be tugged along at L2 by the Earth-Sun system. A lot of the mission operations are simplified by that.

The way for the science to finally begin is paved by this crucial finale. We still have to wait for the observations to start. The first images of the most ancient stars and galaxies in the Universe will be collected by the observatory, and scientists and engineers will soon start aligning the telescope's mirrors.

If the process goes well, the first historical images could be beamed back to Earth as soon as this summer.