The Earth Biogenome Project aims to sequence the genomes of all complex life on earth in ten years.

The project's origins, aims and progress are detailed in two papers published today. It will forever change the way biological research is done.

Researchers will no longer be limited to a few "model species" and will be able to use the database of any organisms that show interesting characteristics. Understanding how complex life evolved, how it functions, and how biodiversity can be protected are some of the things we will be able to learn from this new information.

The project was first proposed in 2016 and I spoke at its launch in London in 2018). It is in the process of moving from a startup to full-scale production.

The goal of phase one is to sequence one genome from every family on the planet. By the end of the decade, one-third of these species should be done. Phase two will see the completion of all the species, and phase three will see the completion of all the genera.

The importance of weird animals.

The goal of the Earth Biogenome Project is to sequence the genomes of all the species of complex life on Earth. All organisms with true nuclei are included.

It's a huge advantage to be able to study other species that may work differently than the model organisms that we know about.

Many important biological principles were derived from studying obscure organisms. The genes that were discovered in peas and the rules that govern them were discovered in red bread mold.

Our knowledge of some systems that keep it secure came from research on tardigrades. Sex chromosomes have been explored in fish and platypus, as well as in mealworms and beetles. The ends of chromosomes were found in the pond scum.

Answering biological questions.

It is possible to discover what genes do and how they are regulated by comparing closely and distantly related species. In a paper published today in PNAS, I and my University of Canberra colleagues discovered that Australian dragon lizards regulate sex by the neighborhood of a sex genes, rather than the sequence itself.

Scientists use species comparisons to trace genes and regulatory systems back to their evolutionary origins, which can reveal amazing conserved genes over a billion years. The same genes are involved in the development of the eye in humans and fruit flies. The BRCA1 gene is involved in repairing DNA breaks in plants and animals.

The animal's genome is much more similar to that of humans. Several colleagues and I recently demonstrated that animal chromosomes are older than 694 million years old.

The "dark matter" of the genome will be explored, and it will be exciting to discover how the non-coding genes can still play a role in the evolution of the genome.

The Earth Biogenome Project is focused on the preservation of genetics. This field uses DNA sequencing to identify threatened species, which includes about 28 percent of the world's complex organisms, helping us monitor their genetic health and advise on management.

It is no longer an impossible task.

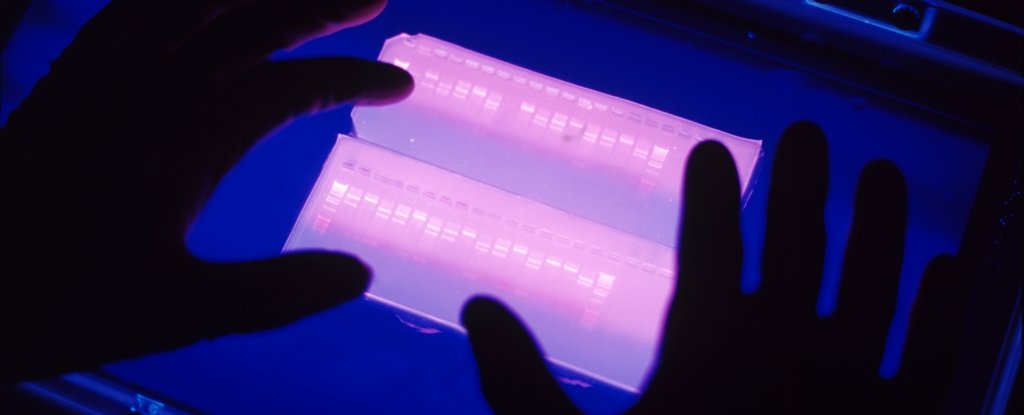

It took years and millions of dollars to sequence large genomes. It is now possible to sequence and assemble large genomes for a few thousand dollars. The Earth Biogenome Project will cost less than the human genome project, which was worth about US$3 billion.

Researchers used to have to identify the order of the four bases on millions of tiny DNA fragments, then paste the entire sequence together again. They can register different bases based on their physical properties, or they can bind each of the bases to a different dye. New methods of decoding the long strands of DNA can be used.

Why don't we just sequence just the key representative species?

The Earth Biogenome Project is about exploiting the variation between species to make comparisons and also to capture innovations in outliers.

There is a fear of missing out. If we only sequence 69,999 of the 70,000 species of nematode, we might miss the one that can reveal the secrets of how the disease can be caused.

There are 44 affiliated institutions working on the Earth Biogenome Project. There are 49 affiliated projects, including enormous projects such as the California Conservation Genomics Project, the Bird 10,000 Genomes Project, and the UK's Darwin Tree of Life Project, as well as many projects on particular groups such as bats and butterflies.

Jenny Graves is a professor at La Trobe University.

The Conversation's article is a Creative Commons licensed one. The original article can be found here.