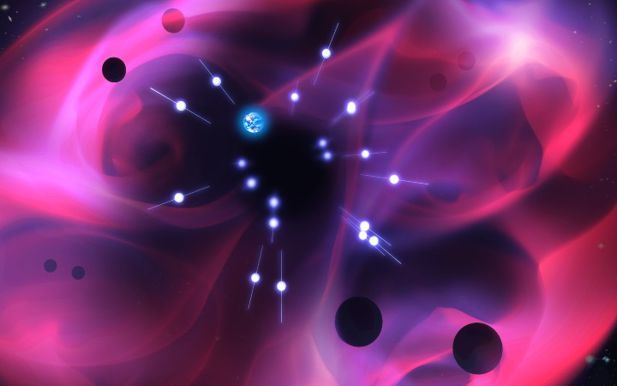

An illustration depicts the signals from millisecond pulsars as they travel towards Earth. Credit: C. Knox.

Scientists observed changes in the signals coming from millisecond pulsars, which may indicate the existence of ripples in the universe.

A millisecond pulsar is a stellar remnant that spins hundreds of times per second and produces precise radio waves. Scientists think that ripples in space-time can affect signals as they travel through space. A team of researchers recently detected a strange disruption to the signals of the pulsars, and decided that it may have been the result of an interplay.

This is a very exciting signal. The leader of the new work said in a statement that they may be starting to detect a background of the waves.

The treasure trove shows black holes.

The detection of waves in 2015 was one of the highlights of the decade. Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity suggested that the fabric of space-time can be undulate when large objects crash into one another, causing ripples that are felt across vast distances. It wasn't until the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO) in the U.S. and the Virgo Collaboration in Europe came about that the detection of these powerful vibrations was made possible.

Some questions remained. Physicists theorize that the amount of ripples produced by these cataclysmic events could have created a background that is present and pervasive in the universe.

The detection of the disrupted signal from the millisecond pulsars may be the first step towards proving the existence of this background.

millisecond pulsars emit radio signals from their poles as they spin. The signals are regular and can be used as a clock against which other phenomena can be timed.

A team of astronomer working as part of the IPTA project detected odd shifts in the signals. They think the disruption may be caused by the interference from the background.

The team acknowledges that other possible explanations for their detections need to be ruled out. The scientist who collaborated on the study said that they were looking into what else the signal could be. "For example, it could be the result of noise that is present in individual pulsars' data that may have been modeled in our analyses."

The combined findings from three independent data sets were collected by the European Pulsar Timing array.

The research was published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

You can follow the person on social media. Follow us on social media.