Multiplesclerosis, an auto-immune disease that affects the brain and spinal cord, may emerge after an exposure to the Epstein-Barr virus.

According to the clinical resource UpToDate, an estimated 90 to 95 percent of people catch the human herpesviruses 4 by the time they reach adulthood.

In teens and young adults, the virus can cause mononucleosis, which is also known as a "mild" infection. There is evidence to suggest that infections with the virus are a risk factor for multiplesclerosis, a less common condition.

Studies have shown that people with multiplesclerosis have high levels of the immune molecule that protects against the virus. There is evidence that catching mono increases the risk of developing multiplesclerosis.

It has been difficult to show that the infections are an underlying cause of multiplesclerosis.

There are new findings about viruses.

A new study in the journal Science provides evidence for this idea. The risk of developing multiplesclerosis increases 32-fold following an infection with the virus, according to a research team that combed through data from 10 million US military members over the course of two decades.

They found no link between the disease and other infections, and no other risk factors show a high increase in risk.

Dr. Lawrence Steinman, a professor of neurology and neurological sciences at the school, said that the study shows that the development of multiplesclerosis can be prevented with the use of the vaccine.

Steinman told Live Science in an email that the research does not explain how the disease might be caused by the virus.

There is compelling evidence.

"We've been working on this hypothesis for about 20 years, and we think it's related to the risk of multiplesclerosis," said Kassandra Munger, a senior research scientist in the Neuroscience Research Group at the Harvard TH.

The team set out to identify people who had never been exposed to the virus, track their status through time, and see if their chance of developing multiple sclerosis increased after exposure.

"This is a challenging hypothesis to test because over 95 percent of the population is infectious with the disease by adulthood," Munger said. The team combed through a unique dataset to identify people with no prior exposure to the disease.

The Department of Defense has a repository of blood from military personnel. Every two years after their service, active-duty military members provide HIV screening and any leftover HIV testing is put in a repository.

The stored samples gave the researchers a way to check the status of each person through time, by checking for the antibodies against the virus.

The team used the data to investigate a possible link between the two. Their data only focused on the individuals who became exposed in their early 20s.

They used medical records to identify 801 people who developed multiplesclerosis during the study period and who had provided at least three samples of their blood prior to their diagnosis.

All but one person became exposed to the virus after 35 of them had tested negative for the specific antibodies. 800 of the 800 caught the disease.

The team ran several tests to see if any other viruses shared the same correlation with the disease, but found that the only one that stood out was the one with the EBV.

There are surprising facts about the immune system.

The team spotted signs of nerve damage in those who developed the disease, but before their officialMS diagnosis.

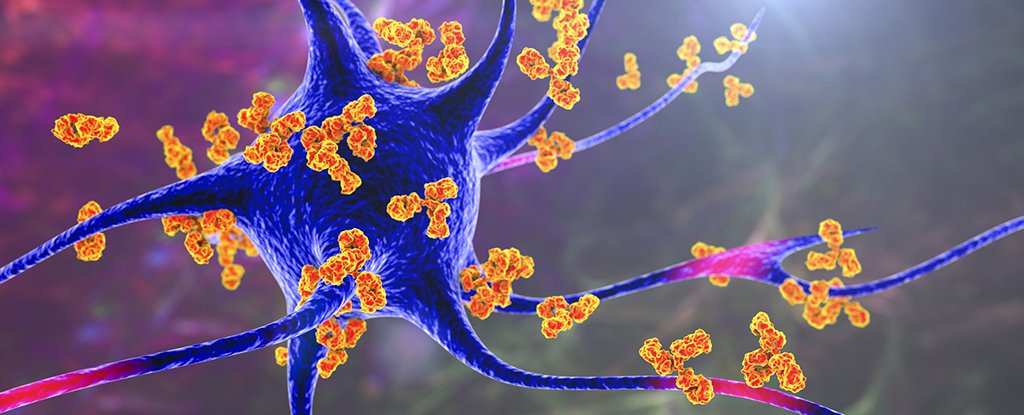

The immune system mistakenly attacks myelin, a sheath that surrounds many nerve fibers, and this damage impairs the ability of nerve cells to transmit signals. The team looked for signs of nerve cell damage in the samples, as early as six years prior to the start of multiple sclerosis.

They were looking for a light chain that goes up in the blood after damage to nerve cells. The people who went on to develop multiplesclerosis had a higher level of thisprotein in their blood.

The control group who never developed multiplesclerosis had the same concentration of neurofilament light chain in their blood after they caught the disease.

Munger said that the infection seems to occur before any evidence of nervous system involvement.

She told Live Science that this is really, we think, compelling evidence of causality.

Robinson said that it was inextricably linked to the development of the disease.

A recent study led by Robinson and Steinman provides some clues as to why this link exists.

The study was posted to the preprint database Research Square on January 11 but has not yet been peer-reviewed or published.

It suggests that people with multiplesclerosis have a lot of specific cells in the brain and spine. The cells that make myelin have a similar looking molecule to the cells that make the antibodies.

Other studies show evidence of the targeting of components of nerve cells and the myelin sheath.

Robinson thinks that the similarity of the viral component to a self protein causes the immune system to attack myelin.

Even with the mounting evidence, one big question remains: Why do some people go on to develop multiplesclerosis when most people catch the disease at some point? The answer is in their genes.

Robinson said that there is evidence that certain versions of genes that regulate the immune system may make a person susceptible to multiplesclerosis.

Within that genetic context, it's possible for EBV to light up the cause of multiplesclerosis. In the future, a vaccine that protects the body against the virus could be used to stop multiplesclerosis, he said.

Steinman and Robinson wrote in a commentary that they thought that the disease could be eradicated.

There is a related content.

There are amazing images in medicine.

There are 11 infectious movies on the big screen.

The most deadly viruses of all time.

The article was published by Live Science. The original article can be found here.