Wari elites added vilca, a powerful hallucinogen, to chicha, a beer-like beverage made from fruit. The researchers say that the combination made for a potent party drug helped those in power bond with their guests and consolidate relationships. The social and political importance of these feasts was boosted by the fact that vilca could only be produced by the elites. The findings of a new study were published today.

Prior to the emergence of the Inca Empire, the Wari state ruled over the Peruvian Andes from 600CE to 1000CE. The Wari outpost at Quilcapampa in Peru was built during the 9th centuryCE and contained evidence of the vilca-chicha mixture. Matthew Biwer, an archaeologist at Dickinson College in Pennsylvania, contributed to the analysis.

Biwer, the first author of the new book, states that Quilcapampa is one of the few investigated Wari sites in the Arequipa province of Peru. The site has provided critical evidence of how Wari operated in the region as well as insights into the Wari-local relationships that developed over the short occupation of the site.

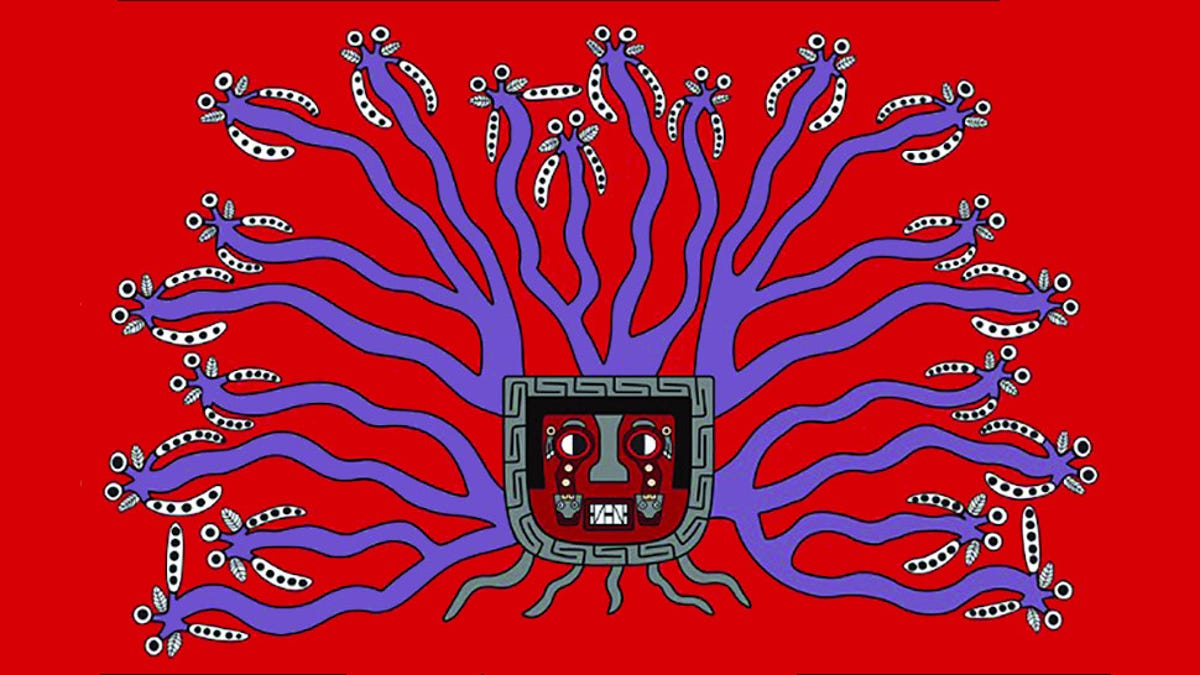

It wasn't clear if Wari individuals partook in Vilca, a drug that dates back thousands of years. The members of the contemporary Tiwanaku state did. The drug has potent psychotropic qualities due to the chemical bufotenine DMT. The Wari people used vilca to get high, but instead of consuming it as snuff, they added it to chicha, which is derived from the fruits of the Schinus molle tree.

Biwer said that the first finding of vilca at a Wari site was a glimpse of its use. We could only assume how it was used, since it was found in burial tombs before. These findings show a more nuanced understanding of Wari politics and how vilca was involved in them.

The site at Quilcapampa provided evidence of both substances, as over a million pea-sized molle dregs, or fruits, were found, and also some seeds of the vilca tree, which is used to produce the hallucinogenic drug. Biwer explained that the archaeological context allowed his team to conclude that the two substances were mixed together.

He said that Vilca is not common at the site. It was limited to certain contexts and not widespread.

There was a central garbage pile located near a pit of molle chicha dregs where vilca was recovered. The close association of the vilca to the molle chicha dregs, the complete absence of snuff paraphernalia at the site, and evidence pointing to a big party, all point to the use of the vilca-chicha mixture in a feast held at Quilcap

The elites hosted these communal feasts to cement social relationships. Biwer argued in his email that beer and drugs allowed the Wari empire to maintain political control.

The ability to provide a feast for guests has powerful social, economic, and political connotations. Food and other resources are given to guests at a feast. This can provide a lot of social and political clout for a host, whose guests witness the economic abilities of the host to provide the feast. A politically charged atmosphere is created by who is invited, what is served, and how much is eaten. The guests of a feast may become indebted to the host who gave them food and drink, not everyone has the means to repay. They would have to repay the host in some way, which would mean real power for the host. Feasts and surplus can be used to create relationships that some people will become indebted to.

The vilca drug seems to have exclusive control over the elites. The nearest source of the tree is more than 250 miles away. It was in the best interest of Wari leaders to control access and use of hallucinogenic seeds because not everyone had the means to procure them.

The new research shows that Wari had access to vilca and that they added it to chicha as opposed to snuff. Biwer said that this is significant because snuff creates a mind-changing experience for an individual, whereas vilca to chicha can provide this experience to many more people. He said that by doing so, Wari began to use the experience to create social relationships and power with locals and other groups.

South Americans had access to a lot of drugs. A 1,000-year-old ritual bundle consists of five different substances, including ayahuasca and cocaine. The bundle was likely the property of a shaman who had a lot of knowledge about plants and where to get them.

Discovery in Mexico sheds light on an ancient game.