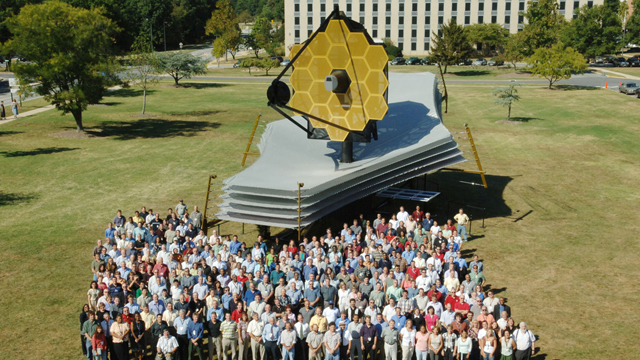

A scale model of a telescope.

Saturday was filled with all of the problems and perils of the world. Around the globe, the Omicron-fueled pandemic raged. The first snowstorm of the season happened in New York. Turmoil continued in other countries.

In space. There was a great triumph in space on Saturday.

After a quarter century of effort by tens of thousands of people, more than $10 billion in taxpayer funding, and some 350 deployment mechanisms, the James Webb Space Telescope has unfurled its wings. The process went smoothly after the final deployment of the massive spaceship.

Thanks to NASA, and space agencies in Europe and Canada, the world has a brilliant new space telescope that will allow humanity to see far further back into the depths of galactic time than ever before, and possibly identify the first truly Earth-like worlds around other stars.

I dare say that most of the world will not know or care about the amount of work that went into building, launching, and deployment of the James Webb Space Telescope. We know, but those of us who know. We are in awe.

After full deployment, NASA's chief of science, Thomas Zurbuchen, said, "This is an amazing milestone."

Scientists wanted to see back further into the early universe, so they started planning for a successor to the Hubble Space Telescope. They would need a dark environment far from Earth to do this. It is necessary to collect light from the most faint objects in the universe in order to avoid background interference.

Advertisement

Scientists planned to build a telescope that would make observations in the part of the spectrum that is just a little bit longer than red light. This portion of the spectrum is good for detecting heat emissions, and it's less likely that they will be hit by dust from the stars.

Scientists came up with a large, tennis-court sized heat shield to block light and heat from the Sun, because a telescope would need to be very cold. The heat shield and telescope would need to be folded to fit inside the protective shell of a rocket. That was the first thing that had ever been tried. It took the better part of two decades to build, test, and deploy the heat shield.

The launch of the telescope on Christmas Day two weeks ago was momentous, but it was just the beginning of the end of the journey from concept to science operations. There were 343 actions where a single-point failure could scuttle the telescope. Many of the scientists and engineers I have spoken with in recent years feel that the chance of a failure in space is very high, because this is a remarkable number of instances without a redundant capability.

The heat shield is working. The temperature on the Sun-facing side of the telescope is 55 degrees Celsius, which is very hot in the desert. The science instruments on the back side of the sun shield have been cooling to -199 degrees Celsius, the temperature at which liquid nitrogen is a liquid. They will cool down further.

Work continues, of course. It will take about 370,000 km to get to a stable Lagrange point, L2. Scientists and engineers check out the mirror segments. Scientific instruments have to be adjusted. When it comes to science spacecraft, all of this work is fairly routine. There are risks, but they are mostly known.

We can be certain that this summer will see the beginning of science observations by Webb. We should be in awe.