The story of the Thai Cave Rescue was excerpted and adapted from Aquanaut: The Inside Story of the Thai Cave Rescue. All rights reserved

A group of young football players and their coach became stranded in the cave system of Northern Thailand in June of last year. The international rescue effort over the next three weeks had the world on edge. The expedition was led by veteran British cave divers, Rick and John, and they would locate the team and bring them out safely.

They would have to rescue themselves on their own. The two divers began their journey deeper into the cave after the rain stopped and the water levels in the subterranean passages continued to rise. They found they were not alone.

The entrance chamber had changed a lot from the night before. The river was cascading from the cave's throat, and it was now a large lake.

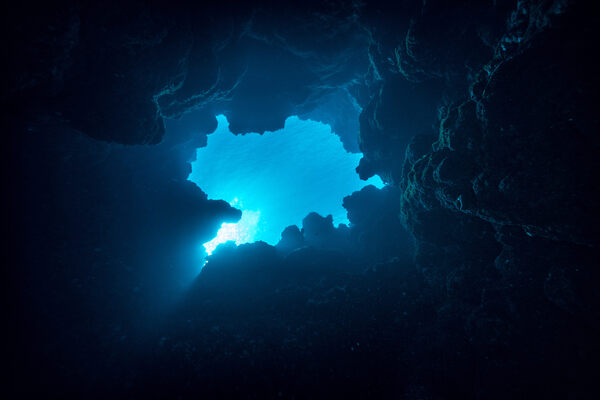

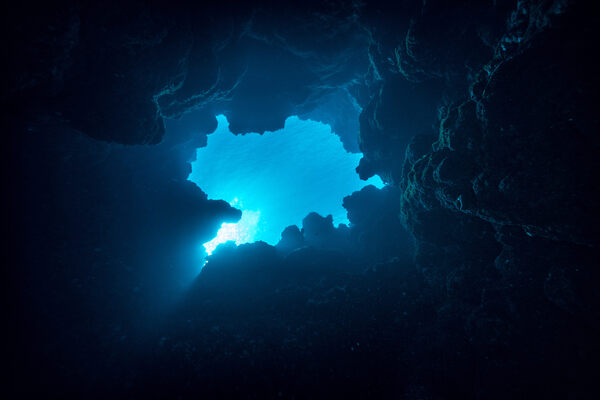

The cave system was flooded in June of last year. YE AUNG THU is pictured.

We were able to walk through the entrance just 14 hours earlier. We went in after slipping our fins over our wellies. We were immersed in the muddy water with no visibility and a vicious current and had to lay line as we penetrated further inside. We were standing in a river that was surging against us after we surfaced at the far end of the sump. John and I are both experienced whitewater kayakers, and our knowledge of navigating through swiftly moving water became useful for us as we walked through, placing ourselves strategically to prevent the force of the current from knocking us off our feet or pinning us against the wall at the corners.

The cave back here was polluted with diesel fuel leaking from the pump beyond Chamber 3. I began to gag. The archway that nearly trapped another diver the previous evening was now four meters underwater. On the other side, we were confused by cables and large clusters of hose as we went towards the large third chamber. John and I were startled to see a flashlight and hear voices.

There is a book aboutASTRO OBSCURA.

The world has something to offer.

A journey through the history, culture, and places of the world of food. Order now.

The boys are here? I was wondering incredulously. Have they found a way out in desperation? I saw that the voices were four men. My initial disappointment was replaced by confusion and then aggravation. What were they doing there?

The men were excited to see us, and the one who came forward as their leader was the most excited of them all. When it became clear that John and I were foreigners who didn't understand the language, he began gesticulating wildly with his hands and arms. The four of them were working on installing the water pumps in Chamber 3. They had been napping in an alcove when everybody else had left. They woke up to find themselves trapped and abandoned.

They must have been here when Rob came in. John said what I was thinking. Has nobody noticed that they have been missing?

During the early stages of the rescue operation, Thai soldiers and locals placed cables and other equipment in the mouth of the cave. LILLIAN SUWANRUMPHA/ Agence France-Presse.

We took off our diving gear and walked around in our wetsuits and wellies. The side of the chamber that was muddy was on this side. There was a dividing rib on the far side of the rock, which had a large sandy plateau on it. The men were trapped in the sand of the rise of the plateau to measure the level of water. The water had risen half a meter in the past half-hour alone, and at the moment, this plateau was less than a meter above water.

We need to take the men out, but how? There were four of them and two of us. We didn't have time to retreat, put together a plan, find reinforcements, or return in time. We held a quick discussion.

They will be treading water before we get back to them if we leave them here.

There is no one else. We would be the ones to save the day.

We have everything we need. Let's do it.

Let's just do it.

Cave divers depend on the continuity of equipment. You should always have at least two things. Each of the harnesses held two cylinders and each had its own demand valve attached to it. We used hand gestures to let the men know that we would be diving them out one at a time, with them breathing off of our spare cylinder. The men seemed to be more concerned about their phones than their rescue. I watched as they carefully wrapped their mobile devices in plastic bags and then put them inside a canvas pouch, which they handed over to me delicately.

None of the men seemed to be very comfortable in the water. I didn't think we'd have a problem because they were desperate to get out and they all seemed willing. One of the younger men was selected to go first. I gave him a regulator to practice breathing through while he was submerged in order to help him acclimatize to being underwater. This is usually helpful in calming a non-diver who would be breathing underwater for the first time, but it didn't work this time. The young man was flailing his arms wildly as he tried to pull his face out of the water. I thought it might be comforting for him to see others go first. We set off underwater after I beckoned to Surapin, who was more agreeable to the learning process.

What an amazing event.

Despite the risk of rapid seasonal flooding, many of the caves in Northern Thailand are popular with locals and tourists. The Alongkotrit Sumjearapol is part of the Images.

He was tethered to me by the hose that was providing his life-sustaining air when he was breathing through the regulator attached to my second cylinder. He would need to be with me. With my arm around his back and my hand on his shirt, I guided him through the difficult terrain. My other hand was holding the line to keep us from being lost.

I knew diving down to the archway on the way out would be awkward, but I wasn't expecting to see the ledges of rock jutting out towards us. The jagged walls and ceiling were hidden by the rocks on the ceiling above us as we ascended. Heading down to go out, they kept catching us as we tried to get through. I was doing everything I could to avoid the rocks. I heard an audible thud when his head hit the ceiling, because I had no way to protect it. After passing through the archway, he must have felt that we were rising, and he became desperate. Surapin tried to swim away from me in an attempt to get to the surface more quickly. I could see that he had lost control. The rescue turned into a wrestling match.

The rescue turned into a wrestling match.

I had to hold him with one hand while keeping my other hand fastened around the line. If he escaped from me, I knew he wouldn't locate the airspace that lay ahead of him, and I would be hard-pressed to find him. We would both be lost if I lost the line. I let go of my grip on him, knowing I would deal with the consequences in a moment after I gained my bearings.

The area where he surfaced was low, with a small airspace between the water and the ceiling. I was hoping he would turn onto his back and keep his nose up, but I heard his head hit the roof as he tried to get out of the water. I ascended and surfaced along the line, gained my bearings and made my way back to him, twisting his head so his nose was sticking into the airspace.

I led him to an area that was large enough for him to breathe comfortably after a few breaths. I guided him to a ledge where he could stand. I clipped the spare reg to its D-ring on my neck strap and dived back to Chamber 3 after he was safely on dry land. John was waiting to see how it went.

I told him that it was exciting. Not in a good way.

While we were on our adventure, John thought that the first worker would have been a lot calmer if he had been wearing a mask. I would lend my mask to the next worker and John would come back with it after the dive. John was hesitant to give his mask over, but he knew he had to. We were having to adapt as we went, and this situation wasn't ideal.

John Volanthen was a partner in the rescue operation. Linh Pham is a photographer.

The dives from Chamber 3 went more smoothly than the first. The current was stronger when John and I left. I wondered if the men had noticed how much water had risen in the twenty minutes since we arrived.

When the men were together again in the second chamber, they were much calmer and I was struck by their resourcefulness when they unplugged one of the electric lights to keep their eyes open. The final dive of the rescue was once again done by me and Surapin. I assumed he still trusted me despite what had happened earlier, but as luck would have it, my light went off just as we descended beneath the surface of the water. I thought it was better to turn around and get the light sorted before diving because I briefly debated continuing in darkness.

When we surfaced, he thought we had reached safety. He ran up the passage to look for the others. I let him go and was confident he would sort himself out. I knew he didn't have a place to go. He came back to me with a quizzical look, not understanding why his friends weren't there. When my light came back on, I said we still had to dive out. He accepted this relatively calmly.

When we got to the entrance chamber, we approached the nearest Thai SEAL as a group. Four men were brought out of Chamber 3. I was struck by how ridiculous the past hour had been when I heard John say those words. The Thai navyman looked a bit bewildered. Fortunately, we had a person who could explain the situation to them. The four men thanked us repeatedly for saving them, but they wanted to be sure that we understood their gratitude in spite of the language barrier. The four men disappeared into the crowd after I handed over their phones.

British cave diver Rick Stanton walks past reporters outside the cave in the early days of the rescue operation. Linh Pham is a photographer.

The rescue mission that day was full of drama and provided valuable lessons that would inform many of the decisions we would make the following week. What did we learn? What would we do differently? Our gears were turning. The boys were not expected to stay calm during a series of dives that would be much longer and more difficult than the dives the men had just struggled with. We had to find a way to account for the panic. We appreciated that today's rescue had provided us clear lessons for what would need to be done, even though neither of us held much hope for finding the boys alive.

Something to protect their heads during the dive out.

We returned to our gear room in a state of silence, still trying to process everything that had happened and wondering what could possibly go wrong next.