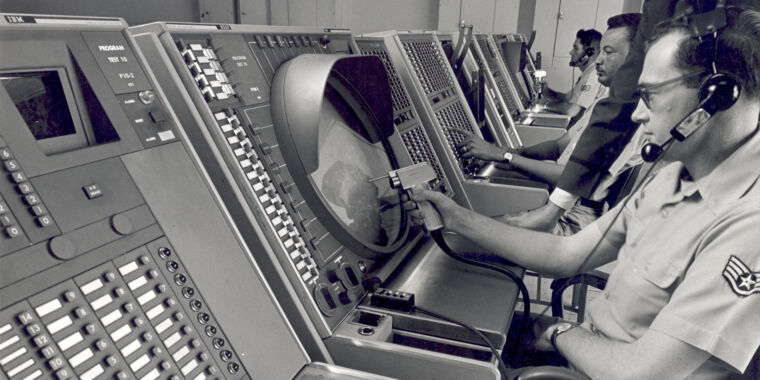

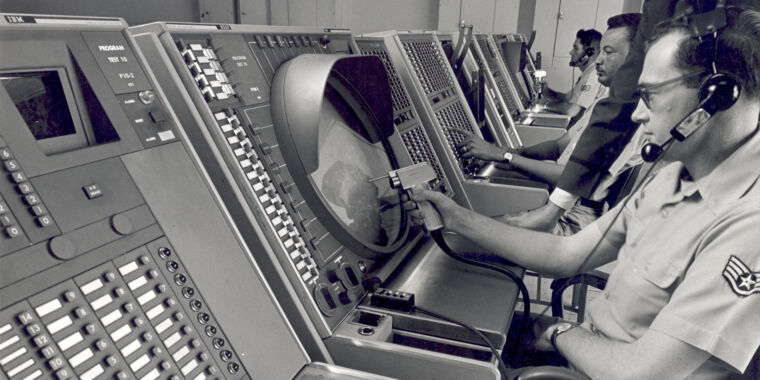

The airmen are operating the radar consoles.

It is not unusual to hear that a particular military technology has found its way into other applications, which have changed our lives. Many of the ideas that were refined to fly on spy satellites, for example, were originally thought to be bad science fiction.

This one did the same thing.

Consider the following scenario.

To protect the United States and Canada, a huge array of radars would be set up. Air Force personnel use high-speed links to a distributed network of computers and radar scope to look for activity in the skies. One day, an aircraft is discovered and headed towards the United States. A quick check of all known commercial flights shows that there was no planeload of holiday travelers lost over the Northern Canadian tundra. All attempts to contact the flight have failed, as it is designated a bogey at headquarters. A routine intercept will fly alongside to identify the aircraft and record registration information.

An attack is coming from Russia before the intercept can be completed. DEFCON 2 is one step below a nuclear war. A high-level picture of the attack is projected on a large screen for senior military leaders. The intercept director clicks on icons on his screen to assign a fighter to his target. All the essential information is radioed directly to the aircraft's computer without the pilot talking to it.

All the data needed to destroy the invader is loaded onto the plane before the pilot is buckled into his seat. The data load is acknowledged in the callout of "Dolly Sweet". Lifting off the runway and raising the gear, a flip of a switch in the cockpit turns the flight over to the computers on the ground and the radar controllers watching the bogey. A map of the area is provided by a large screen in the cockpit.

The entire intercept is flown by the pilot. The aircraft is updated with the latest data from ground controllers. When the target is within the fighter's radar range, the pilot assumes control and fires. The autopilot flies the fighter back to base after a quick evasive maneuver.

This isn't an excerpt from a graphic novel or a current magazine. It is all ancient history. The system was implemented in the year 1958.

The problem of defending North America from Soviet bombers during the Cold War was solved by the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment, called SAGE. After World War II, air defense was largely ignored as the consumer economy exploded. The US felt a need to implement a centralized defense strategy after the first Soviet atomic bomb was tested. In the early 1960's, air defense was fragmented and lacked a central coordinating authority as waves of fast- moving bombers were expected to attack. The technology of the time simply wasn't able to meet expectations, despite countless studies trying to come up with a solution.

Advertisement

Whirlwind I.

MIT researchers tried to design a facility for the Navy that would mimic an aircraft design in order to study its handling characteristics. The approach was abandoned when it became clear that the device wouldn't be fast enough for such simulations.

Whirlwind I, a sophisticated digital system at MIT, has a 32-bit word length, 16 math units, and 2,048 words of memory. The concept of cycle stealing during I/O operations was introduced by Whirlwind I.

The Air Force evaluated the system for air defense after the Navy lost interest in it due to its high cost. Whirlwind I proved that coordinating intercepts of bombers was practical after modifying several radars in the Northeast United States. The development of the first core memory and high-reliability vacuum tubes were key to this practicality. Increased processing made Whirlwind I four times faster than the original design, and these two advances reduced the machine's downtime.