Dark matter is one of the most annoying problems we have with the Universe.

The existence of the universe was first mentioned in the 1930s, but it wasn't until the 1960s and '70s that astronomer Vera Rubin showed that the universe had more matter in it than was thought. Since that time, this dark matter has been shown to exist in study after study, in fact 5 times more abundant than normal matter, and very few if any astronomer doubts its existence at this point.

What is it? Observations ruled out faint stars, rogue planets, cold gas, and other objects that give off little light. Most scientists think it may be in the form of axions, a type of particle that has never been detected. It's a good working hypothesis, but it's not proven.

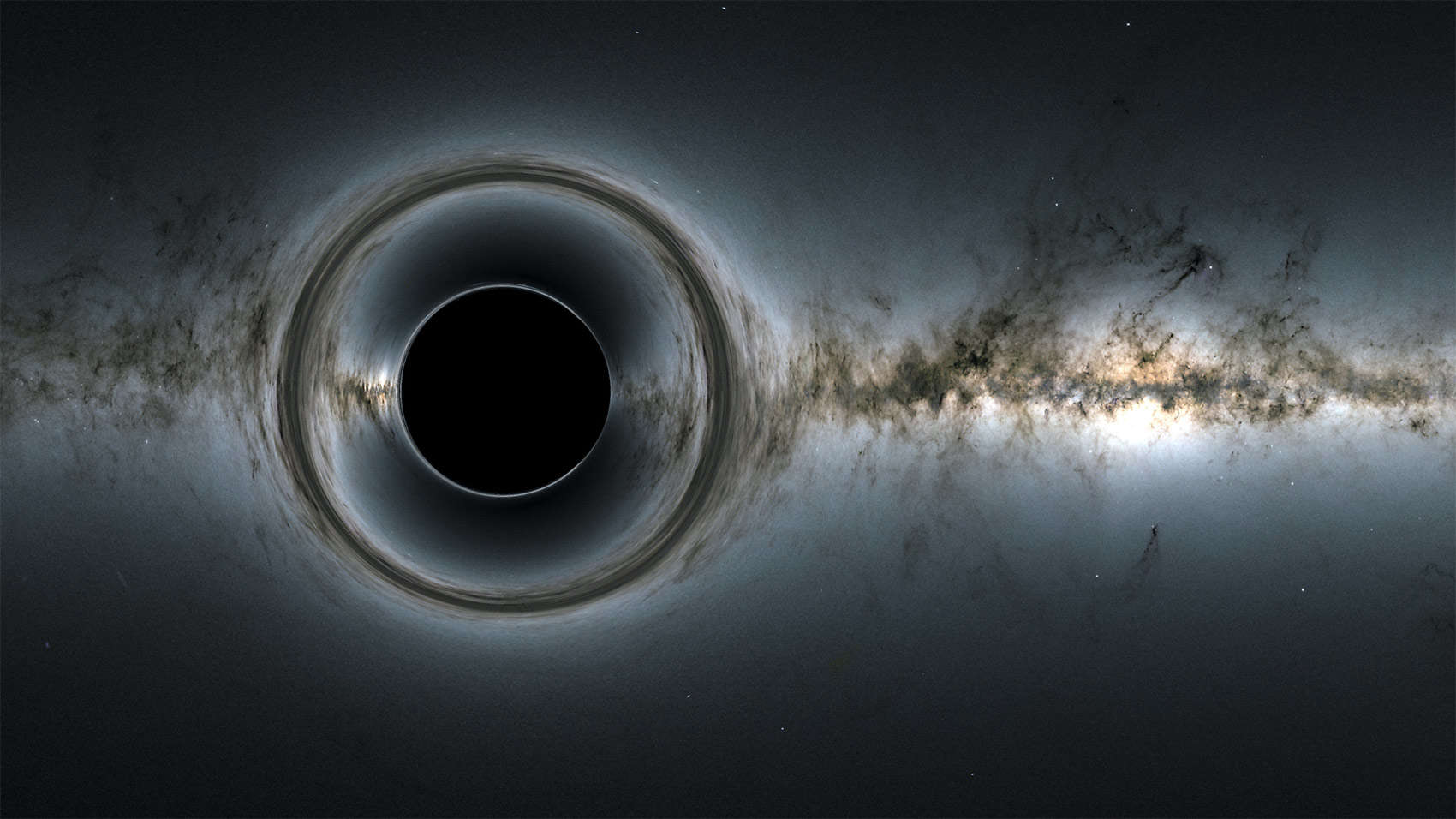

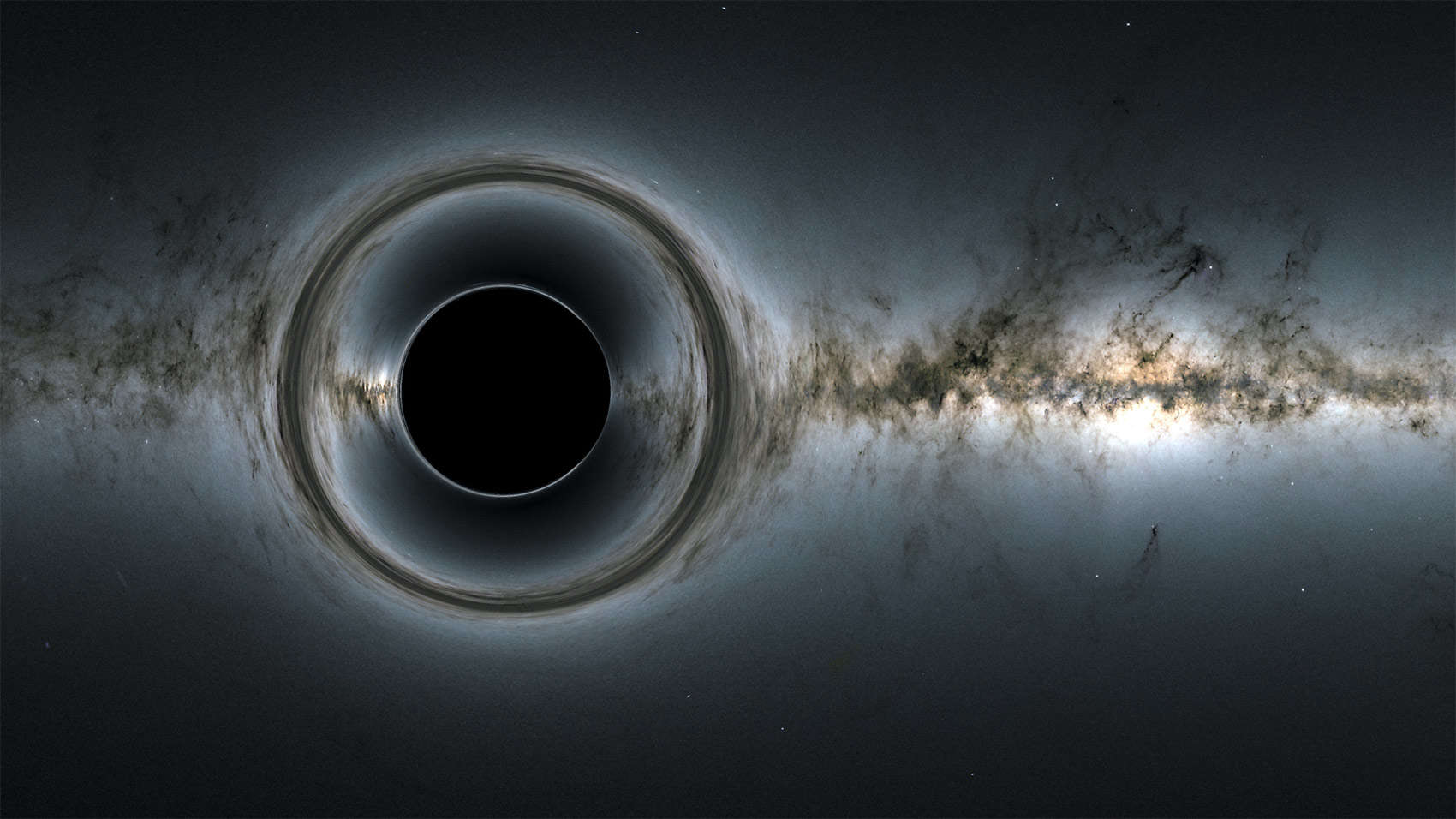

It was thought that dark matter could be made of black holes with less mass than Earth's, and so tiny they'd be hard to detect. They can't be created in the Universe today, but they may have formed in the early Universe. It was very early, like a fraction of a second after the Big Bang.

The idea of black holes as dark matter is compelling, despite some problems with it. A team of astrophysicists has been looking into the possibility, and came up with a scenario they think will solve a lot of problems with other dark matter hypotheses. The way primordial black holes interact and behave explains a lot of what we see today.

The Universe was less than a second old. The amount of matter and energy squeezed into a small volume could cause small regions to increase in density, which could lead to black holes. The very low mass ones were the first to form. When the Universe was a second old, the biggest ones were formed.

haloes are pockets of matter formed by black holes. The biggest black hole in the region would fall to the center of the halo. They would naturally cluster up, forming a variety of systems.

As normal matter formed, it would fall into the haloes. The seeds of the universe were created by the biggest black hole. The smaller black holes formed stars with less mass than the larger ones, which we would consider extremely massive today.

Things evolved according to the models we have today. This idea explains some of the issues with the standard model.

Black holes with billions of times the Sun's mass are found in the edge of the observable Universe. The light that reaches us left some quasars when they were less than a billion years old. It's very hard to form a black hole in a short period of time according to current models, and this has been difficult to explain.

The black holes we see didn't start from scratch. They were primordial black holes that had high mass and could easily grow to enormous sizes after the Universe formed.

A lot of the characteristics of a big galaxies seem to scale with the size of the black hole in their core. The idea of primordial black holes has solved this problem before, for example a bigger early black hole has a longer reach than a lower mass one, so the bigger the galaxies, the more likely they are to be.

Black holes collide and cause ripples in the fabric of the Universe. The black holes seem to be bigger than expected, despite the fact that LIGO and other observatories have spotted dozens of such mergers. Most black holes would be lower in mass than the Sun's, but they should top out around 50 times the Sun's mass. Too many of the mergers come from high-mass black holes. It makes sense if a wide range of primordial black hole mass formed early on. We'd see some in the mass range where it's hard for stars to make them.

These extra black holes would add mass to a galaxy without giving off light, making them the constituents of the dark matter we see almost everywhere. The fact that they can cluster together early on makes them hard to spot observationally, but if they are evenly distributed all over space their effects would be more frequent, so this doesn't necessarily contradict observations made looking for dark matter.

Is it possible that dark matter is made of primordial black holes? Maaaaybe. It's still early in the game, but I find this idea pretty interesting. This idea makes some predictions that can be tested. If this idea is correct, stars would form much earlier in the history of the Universe. That can be observed by the JWST, which is currently on its way to its new home in space. Black hole mergers in the early Universe are predicted to be far more frequent than we'd expect. That could be measured by the upcoming space-based mission called LISA, or by a current program to look for these waves.

We may know soon if primordial black holes can be observed. Scientists can continue to play with the idea and see what else they can come up with, even if that undermines the possibility of their existence.